Running Shoes Changed How Humans Run

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When you strap on a typical running shoe, you may be fighting evolution.

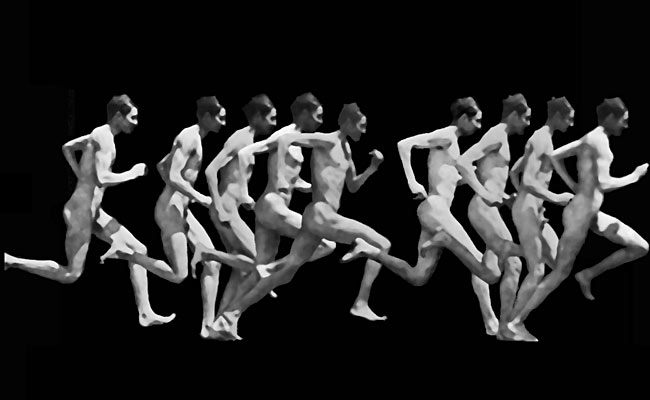

Modern-day running shoes have changed the way people run, altering our gait from that of barefoot running — the manner by which people ran for thousands of years before the arrival of the cushioned shoes found on store shelves today — a new study suggests.

The study showed barefoot runners tend to hit the ground toe first, a style that minimizes forces that jar the body, while people used to running shoes have largely adopted a heel-first style that can mean lots of force on the body.

While several studies have compared running barefoot to running with shoes, the current study, published this week in the journal Nature, is the first to include analyses of runners who have never worn modern footwear, the researchers say.

Humans started wearing running shoes only relatively recently, with use of this footwear taking off in the last 40 years. Before that, people either ran barefoot or wore shoes that would seem to offer little protection from the ground, such as sandals or moccasins.

For nearly as long, people have debated which is better. While the new study may not solve the vigorous debate, it does add data on the physiological effects of running shoes.

The researchers aren't suggesting runners ditch their shoes. For one, barefoot running can take getting used to, and it takes stronger muscles, so the switch could lead to tendonitis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Heel-toe or toe-heel?

When you run, every step you take puts forces on your body, caused by the impact of your foot colliding with the ground. If you land with your heel first, a so-called "rear-foot strike," this impact force is quite large, several times your weight, and occurs over a very short period of time.

"It's like someone hitting you on the heel with a hammer two to three times your body weight," said study researcher Daniel E. Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University.

Runners with modern shoes usually strike the ground with their heel first, although the cushioning present at the rear of many running shoes can lessen this impact force.

But since we haven't always had this heel protection, Lieberman and his colleagues wanted to find out how humans were able to hold up against these forces when they ran barefoot.

They examined the running styles of five different groups: athletes from the United States who always wear running shoes; athletes from the Rift Valley Province in Kenya who grew up running barefoot, but now don modern running shoes; U.S. runners who used to wear shoes, but now go barefoot; and runners from Kenya who either always wear shoes or have never worn shoes.

They saw that runners who were used to running in shoes most often strike the ground heel first, even when running barefoot. Those individuals who grew up running barefoot, or switched to running barefoot, usually landed with their toes first, a so-called "fore-foot strike."

The barefoot runners, including those who grew up running sans shoes and those who had recently switched to barefoot, sometimes landed on their mid-foot as well, but they were much less likely to land on their heel.

Lieberman and colleagues also compared the impact forces generated when runners hit the ground with their heel first versus toe first. They found that heel-striking caused a large impact force, and this force was even greater if the runners were not wearing shoes. In contrast, there was almost no collision force if the runners landed on their fore-feet.

The researchers suspect that barefoot runners land on their toes or mid-feet to avoid the impact they would feel if they landed their heel. They figure barefoot runners point their toes more at each foot strike, which effectively decreases the weight of the foot that comes to a sudden halt at that moment. The pointed toe also means a springier step, which can also decrease the forces.

"We hypothesize that this is how people generally ran before cushioned shoes with elevated heels were invented," Lieberman told LiveScience in an e-mail.

Going barefoot

Running barefoot has become somewhat trendy lately thanks to the best-selling book "Born to Run" (Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), by Christopher McDougall, in which the author argues that barefoot running is better for you, and in which he mentions Lieberman's previous work.

Lieberman stresses that running shoes have not been shown to increase injuries, nor has barefoot running proven to reduce damage to the body. However, Lieberman notes that a recently published study on the topic showed no studies that demonstrate modern running shoes prevent injuries.

While there is anecdotal evidence that striking the ground with your toes first or mid-foot may help reduce injuries, such as stress fractures and runner's knee, future studies are needed to determine whether this type of running style actually decreases injury rates, he said.

Some argue that running barefoot on hard, manmade surfaces is not good for your body. "You run on something hard, your body has to work that much harder to help absorb those forces, and that can lead to stresses and strain," Dr. D. Casey Kerrigan, a former professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Virginia, told LiveScience this month.

But Lieberman says that's not the case. Since barefoot runners more often land on their forefoot, the collision force is virtually eliminated. This finding held true even when the study participants ran on steel plates.

"You can run barefoot or in minimal shoes on the world's hardest surfaces and generate almost no collision [force]," he said.

But what about encounters with glass or a rocky surface? Lieberman and his colleagues admit that treading on such debris will hurt, and suggest you use prudent judgment when deciding on a place to run barefoot. And they emphasize that you should only run barefoot if you want to.

Going barefoot does have its risks. If you are used to striking the ground with your heel first, it can take a while to train your body to land with your fore-foot first. And since this running style requires stronger feet and calf muscles, changing gaits may put your at risk for developing Achilles tendonitis, the researchers say.

The study was funded the National Science Foundation, Harvard University, and Vibram USA, among others. Vibram is a shoe company that markets a type of minimal running shoe.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus