Sense of Beauty Partly Innate, Study Suggests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Is art beautiful because we are taught so, or are notions of beauty hard-wired into the brain?

When people were shown pictures of sculptures in a new study, brain scans suggest they judged beauty by at least partly hard-wired standards.

Researchers in Italy showed volunteers original and distorted images of Classical and Renaissance sculptures. The scientists picked 14 volunteers with no experience in art theory to try to see what role pure biology had to do with judging art.

The golden ratio

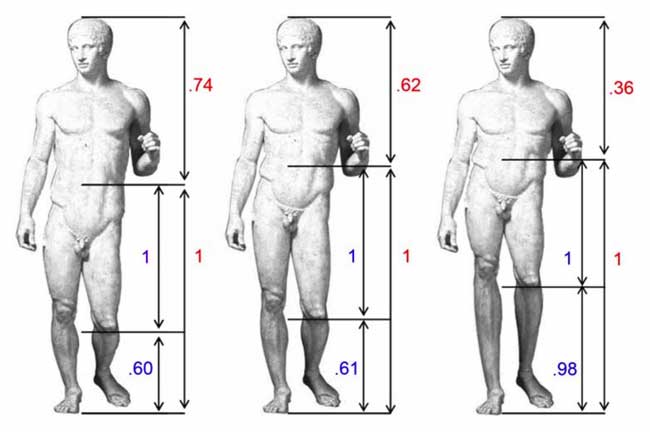

The proportions of the statues themselves reflect "the golden ratio," a mathematical figure known since ancient Greece that Renaissance artists often thought embodied ideal beauty. In nature, the golden ratio can be found in the way nautilus shells curve or how seeds spiral on strawberries. It describes hurricanes, galaxies and the flight pattern of a falcon on the hunt.

Specifically, the golden ratio is equal to roughly 1.618. It is unique in that its value is equal to the ratio of its integer part to its fractional part—that is, 1.618 is roughly equal to 1 divided by 0.618.

In art, the golden ratio has arguably been found in the Parthenon in Athens, the Great Pyramid of Giza and the Mona Lisa.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Strong reactions

The proportions of the sculptures in the study followed the golden ratio. And the original images of them strongly activated sets of brain cells that the distorted images did not—including the insula, a brain structure that mediates emotions.

"We were very surprised that very small modifications to images of the sculptures led to very strong modifications in brain activity," researcher Giacomo Rizzolatti, a neuroscientist at the University of Parma, told LiveScience.

In addition, instead of asking volunteers to simply enjoy these pictures, the researchers also had them judge how beautiful or ugly each was. The images thought of as beautiful activated the right amygdala, a brain structure that responds to memories laden with emotional value. (The original images were often judged by the test subjects as more beautiful than distorted ones.)

The results indicate that the sense of beauty is based on hard-wired notions triggered in the insula and one's experiences, and then activated in the amygdala.Still, the scientists caution the findings cannot necessarily be generalized across cultures.

"We only know that Classical and Renaissance art is generally considered beautiful in Western culture," said researcher Cinzia Di Dio, a neuroscientist at the University of Parma. "It would be interesting to propose a similar study across cultures to see whether these principles are universal or culture-bound."

Remaining questions

Future work can also investigate how the brains of art experts respond, the researchers said. In addition, experiments could try showing artwork other than sculptures to subjects—for instance, paintings.

The study leaves an interesting open question: When a given trend in art fades, can any examples of such work survive "without a resonance induced by some biologically inherent parameters?" Di Dio asked.

The scientists detailed their work online Nov. 20 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus