Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Smart kids don't necessarily have bigger brains than their peers, but the parts of their brains involved in thinking change more during adolescence.

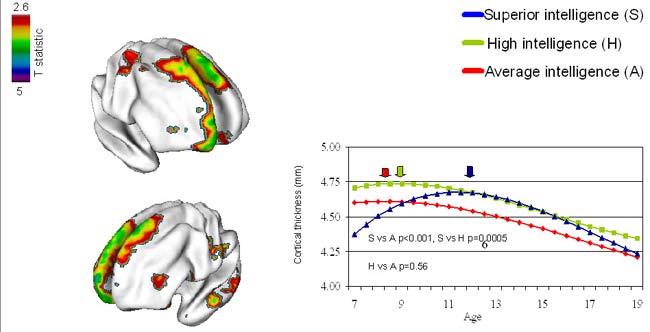

As children grow up, the outer mantle, or cortex, of their brains thicken and thin as new neural connections are being made and then pruned to become more efficient. Using brain scans, researchers have found that the cortices of kids with high IQ scores thickened faster and for a longer period of time than children of average intelligence.

The findings are detailed in the March 30 issue of the journal Nature.

Longer development window

Researchers used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to scan the brains of 307 children at several points during development from the ages of about 6 to 20. Most of the children were scanned at least two times, at two-year intervals.

The children's intelligence was measured using the Wechsler IQ test, which tests verbal and non-verbal knowledge and reasoning. Based on the scores, the subjects were placed in one of three groups: superior (121-145), high (109-120) and average (83-108).

The scans showed that the cortices of all the children's brains thickened during childhood before thinning again.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The cortices of the smartest 7-year-olds in the group, as an example, started out thinner than average but thickened until age 11 or 12 before thinning. Cortex thickening in children with average IQ, in contrast, peaked at about age 8, and displayed only gradual thinning afterwards.

This could reflect a longer developmental window for high-level brain circuits, the researchers said.

Agile minds

The cortices of the smart kids also thinned faster during their late teens, likely due to more efficient pruning of unnecessary neural connections, said study leader Philip Shaw from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

"People with agile minds tend to have a very agile cortex," Shaw said.

Most of the changes were seen in the prefrontal cortex, an area known to be involved in thinking and other higher-level cognitive functions. This makes sense, Shaw said.

"The parts of the brain where the [changes] are most different are also those that are the seat of complex thought."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus