King Tutankhamun: Life, death and mummy of ancient Egypt's boy pharaoh

Tutankhamun, also known as King Tut, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh whose lavish tomb became world-famous upon its discovery in 1922.

Tutankhamun, often called King Tut today, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who was buried in a lavish tomb filled with gold artifacts in the Valley of the Kings. His tomb was discovered in 1922 by an archaeological team led by British Egyptologist Howard Carter. While Carter gets much of the credit for discovering the tomb, most of the actual work was done by Egyptians.

King Tut is sometimes called the "boy king" because he ascended the throne at age 9 or 10, in the 14th century B.C. He died about a decade later. His treasure-filled tomb was discovered mostly intact, which is extraordinary given that most of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings had been looted in ancient times.

The discovery of his tomb in 1922 attracted worldwide attention and turned King Tut into a household name. "It's difficult to imagine the past century without Tutankhamun and the discovery of that time-capsule tomb," Christina Riggs, a history professor at Durham University in England, wrote in her book "Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century" (PublicAffairs, 2022).

"There would have been no media frenzy of Tut-mania and mummy curses to kick-start the jazz age, and no surge of corresponding pride in the newly independent nation-state of Egypt [which had declared independence from Britain in 1922]," Riggs wrote.

Although Tutankhamun's tomb was lavish, historical and archaeological evidence indicates that the young pharaoh was sickly and spent his short rule undoing a religious revolution started by his father, Akhenaten.

Son of Akhenaten, a revolutionary

King Tut, called Tutankhaten at birth, was born in ancient Egypt around 1341 B.C. His father, Akhenaten, was a revolutionary pharaoh who tried to focus Egypt's polytheistic religion around the worship of the sun disk, the Aten. In his fervor, Akhenaten ordered the names and images of other Egyptian deities to be destroyed or defaced. He also built a new capital at what is now Tell el-Amarna. He was able to carry out these acts without a widespread violent rebellion, but Akhenaten was condemned after his death, Anna Stevens, an Egyptologist at Monash University in Australia, wrote in her book "Amarna: A Guide to the Ancient City of Akhetaten" (The American University in Cairo Press, 2021).

Tutankhaten's biological mother is unknown but likely was not Akhenaten's principal wife, Queen Nefertiti — although Egyptologists still debate this, Bob Brier, an Egyptologist at Long Island University, wrote in his book "Tutankhamun and the Tomb that Changed the World" (Oxford University Press, 2022).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tutankhamun ascended the throne around 1332 B.C. Given his young age, the boy king would have relied heavily on advisers. At some point, he changed his name from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun, removing the word "aten" — a reminder of his father's attempted religious revolution — and replacing it with "amun," Brier wrote. This name belonged to an important Egyptian god who some Egyptians regarded as the king of the gods. This change illustrates King Tut's move away from his father's religious changes, returning Egypt to its former polytheistic beliefs.

Tutankhamun condemned his father's actions in a stela found at Karnak, near modern-day Luxor, which stated that Akhenaten's religious revolution had caused the gods to ignore Egypt. Part of the stela reads, "the temples and the cities of the gods and the goddesses, starting from Elephantine [as far] as the Delta marshes … were fallen into decay and their shrines were fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass. … The gods were ignoring this land." (Excerpt taken from "The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and Its People" (Thames & Hudson, 2012)). This act may have helped him cement his power.

Who was King Tut's wife?

Tutankhamun married his half sister Queen Ankhesenamun, and the couple's twin daughters were stillborn; their fetuses were buried in jars in the pharaoh's tomb. The couple left no heir to the throne. The tomb of Queen Ankhesenamun has not yet been found.

Surviving letters indicate that after Tut's death, Ankhesenamun tried to remain on the throne, even going so far as to write to Suppiluliuma I, the Hittite king in Anatolia, to send one of his sons to marry her. Suppiluliuma I found this difficult to believe but eventually sent one of his sons, who died during the journey. Ankhesenamun was eventually forced to marry the official Ay, who became pharaoh.

What did King Tut look like?

A 2010 study of King Tut's remains published in the journal JAMA found that he was 5 feet, 6 inches (1.67 meters) tall and had a variety of medical conditions and illnesses, including malaria and Kohler disease, a rare bone disorder of the foot. Archaeologists also found a number of canes in Tutankhamun's tomb, which suggests the pharaoh had difficulty walking at times.

Despite these maladies, he may have worn armor — although whether he went into battle himself is unclear. A 2018 analysis of leather armor found in Tutankhamun's tomb revealed that the armor had been worn.

"Tutankhamun looked like a person who was suffering physically," Zahi Hawass, a former minister of Egyptian antiquities and co-author of the JAMA paper, previously told Live Science in an email. "He limped and used a stick to walk. He had malaria."

Hutan Ashrafian, a clinical lecturer in surgery at Imperial College London, said Tutankhamun would have walked with a limp, had a slightly longer-than-normal skull, had somewhat enlarged breasts (from a condition called gynecomastia, caused by hormonal imbalances), had buckteeth and been relatively skinny. He was "relatively frail in physique," Ashrafian, who has studied Tutankhamun and his mummy, previously told Live Science.

How old was King Tut when he died?

The boy king died around 1323 B.C. at about age 18. His death was likely unexpected, and his tomb appears to have been hastily finished. In 2011, Ralph Mitchell, who was then a professor of applied biology at Harvard University, helped analyze brown spots in the tomb. Those spots turned out to be the remains of microbes that had once grown on the walls, possibly as a result of paint that was still wet when the pharaoh was interred. "We're guessing that the painted wall was not dry when the tomb was sealed," Mitchell said in a statement.

How did King Tut die?

How King Tut died is a matter of debate among scholars. Egyptologists have put forward numerous hypotheses over the years. In the JAMA article, a research team suggested that a combination of malaria and necrosis (tissue death) from a broken bone in his left foot may have caused his death.

Despite Tutankhamun's health issues, historical and archaeological remains suggest that he tried to keep active, and the broken bone may have come from an accident while hunting. "He liked to hunt wild animals and built a palace near the Sphinx for hunting," Hawass said. "Despite any physical issues, he was active enough to have an accident and injure his leg two days before he died."

Where is King Tut's tomb?

King Tut was buried in an extravagant tomb in the Valley of the Kings, near modern-day Luxor. This valley held the tombs of many pharaohs who lived during the New Kingdom period (circa 1550 to 1070 B.C.) of Egypt's history. During that time, Egypt stopped building pyramids for pharaohs and instead interred them in this valley. Security concerns relating to tomb robbery may have been one reason pharaohs were buried in the valley.

What's inside Tutankhamun's tomb?

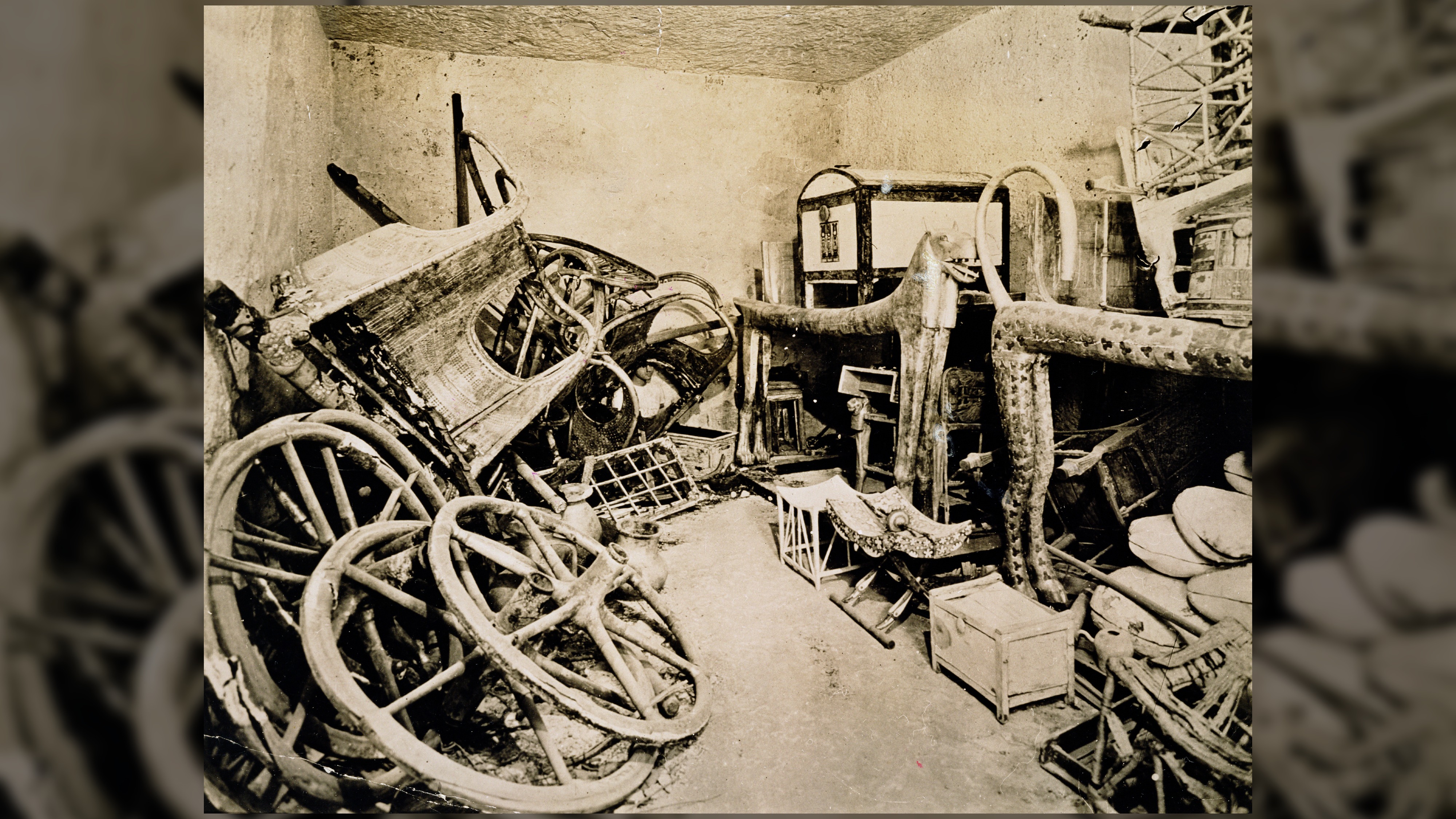

Carter's team discovered the tomb's entranceway on Nov. 4, 1922, and entered the tomb on Nov. 26.

"As one's eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another," Carter wrote in his diary of the dig.

Carter and his team found that the tomb contained a wealth of untouched treasures. "Our sensations and astonishment are difficult to describe as the better light revealed to us the marvelous collection of treasures: two strange ebony-black effigies of a King, gold sandalled, bearing staff and mace, loomed out from the cloak of darkness; gilded couches in strange forms, lion-headed, Hathor-headed, and beast infernal …" Carter wrote in his diary, which is available online at the Griffith Institute at the University of Oxford. Among the many other treasures was a dagger whose iron came from a meteor and a golden throne that has two lions projecting outward as if protecting the throne.

Among the finds was the mummy of Tutankhamun himself. In a 2013 study published in the journal Études et Travaux, Salima Ikram, a professor of Egyptology at The American University in Cairo, suggested that returning Egypt to its traditional polytheistic beliefs was so important to Tutankhamun and his advisers that he requested to be mummified in an unusual way to emphasize his strong association with Osiris, the god of the underworld.

Ikram wrote that Tutankhamun's skin was soaked in oil after his death, which turned his skin black. His heart was also removed, even though the Egyptians did not normally remove the heart. Additionally, his penis was mummified at a 90-degree angle, which was also unusual. In legend, Osiris had black skin, strong regenerative powers and a heart that had been hacked to pieces by his brother Seth.

However, the large amount of flammable oil caused Tutankhamun's mummy to catch fire shortly after his burial.

While King Tutankhamun's riches are incredible, the tomb was unusually small for a pharaoh's burial, with a total volume of 9,782 cubic feet (277 cubic meters), the Theban Mapping Project website notes. Tut's tomb is divided among the passage corridor, the burial chamber, the antechamber, and two rooms now called the "annex" and the "treasury." In comparison, the tomb of Seti I (reign circa 1294 to 1279 B.C) has a volume of 67,110 cubic feet (1,900 cubic m), according to the mapping project.

The tomb may be small because the pharaoh died young and unexpectedly, leaving no time to carve out a larger tomb. It's possible that the tomb was not originally intended for a pharaoh at all, Richard Wilkinson, an Egyptology professor at the University of Arizona, wrote in a paper published in the book "The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings" (Oxford University Press, 2014).

"The tomb of Tutankhamun is not of royal design, and it may have been hastily taken over for his burial when the young king died and [the] tomb that was being prepared for him was not yet complete," Wilkinson wrote. Despite the name "Valley of the Kings," people who were not pharaohs were also buried there.

In 2015, Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves, an independent scholar, published a paper in the periodical Amarna Royal Tombs Project suggesting that Nefertiti was also buried in King Tut's tomb and that her burial remains hidden behind a wall. However, ground-penetrating radar surveys have failed to find solid evidence of a hidden burial.

King Tutankhamun's mask

The most iconic treasure in King Tut's burial chamber is his death mask, made of gold along with inlaid stones and glass. The "mummy mask of Tutankhamun is made of two sheets of solid gold inlaid with glass, faience [glazed ceramic], and semiprecious stones" and weighs 22.5 pounds (10.2 kilograms), Susan Allen, a senior research scholar at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote in her book "Tutankhamun's Tomb: The Thrill of Discovery" (Met Publications, 2006).

Resins and oils were poured over this mask, along with the rest of the mummy, Allen noted. As the resins and oils cooled, they darkened and hardened.

What is the curse of King Tut's tomb?

Within months of the discovery of King Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922, the man who financed its excavation — George Herbert, the fifth Earl of Carnarvon in England — became ill and died. It didn't take long for people to question whether a "mummy's curse" had doomed the earl. Newspapers perpetuated the myth that the opening of Tutankhamun's tomb awakened a curse that killed those who helped find it.

"Pharaoh's 3,000 year-old Curse is Seen in Illness of Carnarvons" read the headline on the front page of the March 21, 1923, edition of "The Courier Journal," a newspaper published in Louisville, Kentucky.

The mummy's curse was refuted in a 2002 study in The BMJ, which examined the records of 25 people who went into the tomb shortly after its discovery. People who entered the tomb lived, on average, to age 70 and lived an average of 20 years after being inside the tomb. Those numbers were not unusual given the average life span at the time and the age of those who entered the tomb, the researchers noted.

King Tutankhamun's legacy

The discovery of Tutankhamun's intact tomb and the media sensation around it have made King Tut more prominent in death than he was in life. This "long-lost king, buried before he was out of his teens, found more fame and influence in the twentieth century than he had ever known in his own life-time," Riggs wrote.

That worldwide fame continues today, and his tomb, known as KV 62, is a major tourist attraction. But tourist entry is strictly managed, as changes in humidity, brought about by people passing through the tomb, can damage the tomb and its wall paintings. To help mitigate the risks, the Getty Conservation Institute conducted conservation work on the tomb between 2009 and 2019. During this time, the conservation team installed a new ventilation system in the tomb and conducted a detailed check of the wall paintings.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Western powers shipped Egyptian archaeological treasures home to their own museums and private collections. As a result, Egyptian authorities enacted laws to ensure that Tutankhamun and his treasures would remain in Egypt, Richard Parkinson, an Egyptology professor at the University of Oxford, wrote in a chapter published in the book "Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive" (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2022).

Additional resources

The Griffith Institute maintains a detailed archive of material from the excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb, much of which can be accessed on the institute's website. Egypt's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities has images from the tomb and information on how to visit. The ministry also has a virtual tour of the Tutankhamun artifacts on display in the Egyptian Museum.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on April 1, 2016, and was updated on April 10, 2024.

Ancient Egypt quiz: Test your smarts about pyramids, hieroglyphs and King Tut

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.