Mysterious Brown Spots on King Tut's Tomb Are 'Dead'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

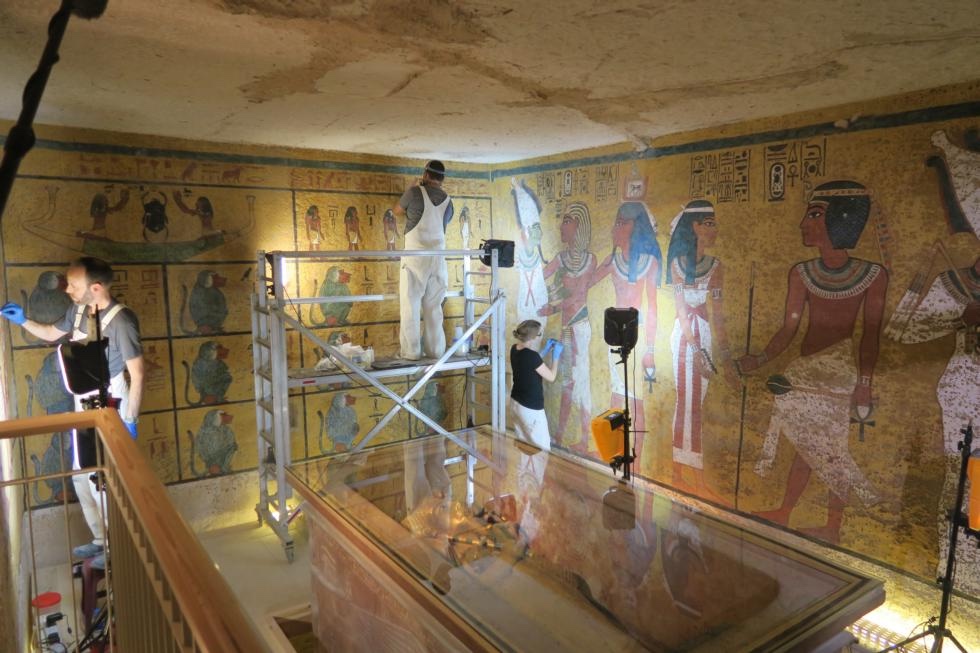

Conservators have nearly completed work at the tomb of King Tutankhamun in Egypt, and they have some good news: The wall paintings are stable, and mysterious brown spots found on the ancient artwork are not growing larger as previously feared.

First discovered in 1922 by the British Egyptologist Howard Carter, Tut's tomb became the most famous in Egypt because of its pristine condition. Unlike many of the other royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings, near the ancient capital in Luxor, Tutankhamun's burial chamber had evaded treasure-seeking looters for more than 3,000 years.

Tutankhamun was born around 1341 B.C., during Egypt's New Kingdom. He ascended the throne at age 9, and died around age 18. The entrance to Tut's tomb had been blocked by mud and rocks from flooding soon after his death. As a result, Carter found the tomb largely intact, still holding the mummy of the king in an elaborate sarcophagus. [In Photos: The Life and Death of King Tut]

For the past decade, the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) in Los Angeles has been working with Egypt's antiquities ministry on a conservation project at Tutankhamun's tomb that included some infrastructural changes, like a new ventilation system and a check of the wall paintings. The GCI announced this week that the work is nearly done and that the wall paintings are relatively stable and not deteriorating much.

The site became a major tourist attraction over the past century, which had created some conservation concerns. (A replica of the tomb was even unveiled in 2014 in an attempt to relieve some of the crowding.) Tourists bring dust into the tomb, which then needs to be cleaned from the walls, and can lead to paint loss, according to the GCI. The constant flow of visitors also alters the humidity and carbon dioxide levels in the once-sealed chamber.

"Humidity promotes microbiological growth and may also physically stress the wall paintings, while carbon dioxide creates an uncomfortable atmosphere for visitors themselves," Neville Agnew, the conservation project leader, from the GCI, said in the announcement. "But perhaps even more harmful has been the physical damage to the wall paintings. Careful examination showed an accumulation of scratches and abrasion[s] in areas close to where visitors and film crews have access within the tomb's tight space."

But apart from these scratches and some flaking, the wall paintings seem to be in stable condition, the GCI announced. The project leaders said that new barriers have been installed to restrict visitor access and thus minimize damage in these sensitive areas.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

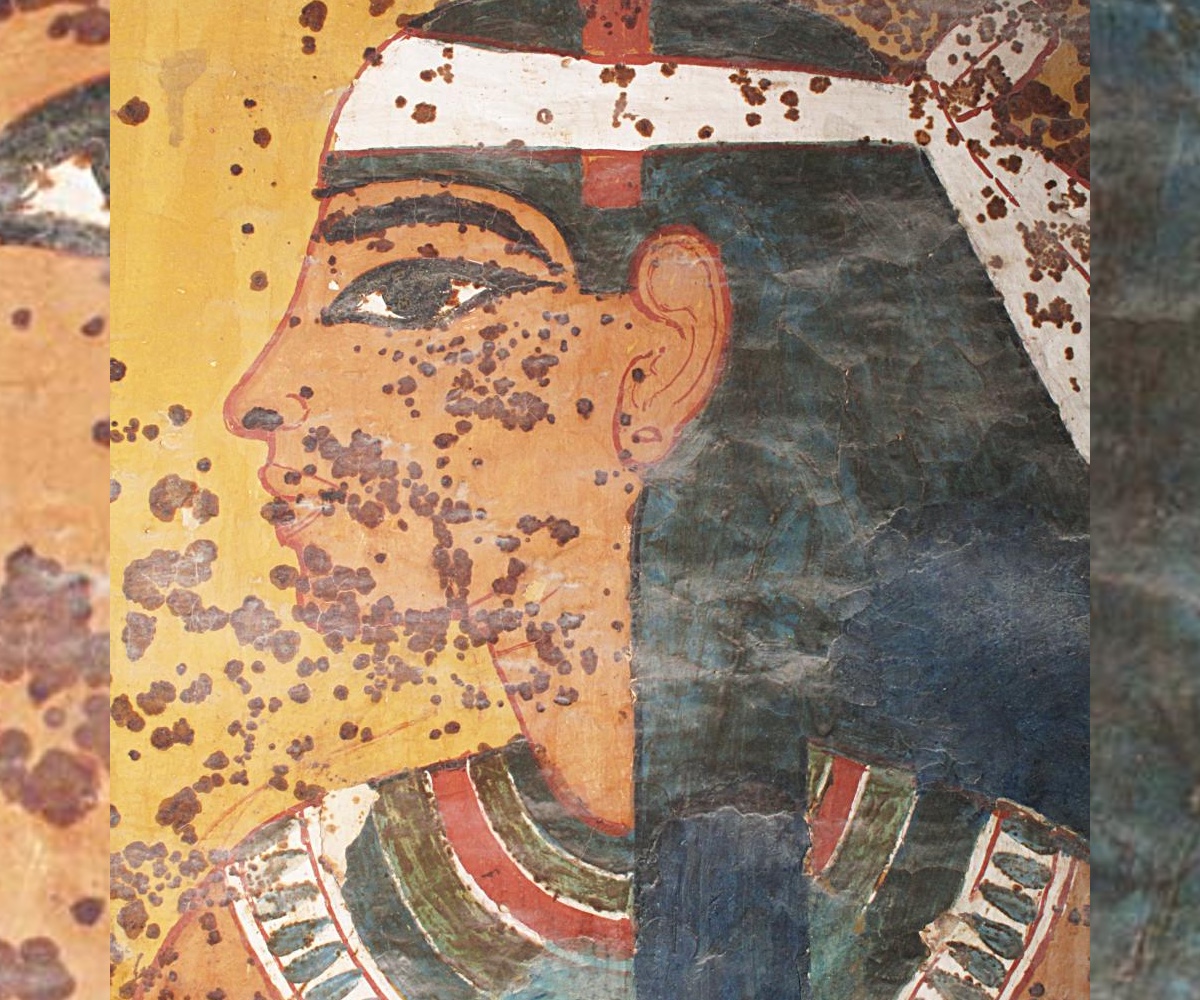

The conservators also investigated the brown spots that have been present on the wall paintings since Carter unsealed the tomb. Researchers had been worried that the spots were some kind of fungus that might pose a threat to the paintings.

DNA and chemical analysis confirmed that the spots were microbiological in origin — so they could be a type of fungus — but these microbes were dead and no longer a risk, the researchers said.

"Because the project allowed for unprecedented study of the tomb and its wall paintings, its findings have provided a deeper understanding of tomb construction and decoration practices from the New Kingdom," Lori Wong, a project specialist at the GCI, said in a statement. "This work has also shed new light on the tomb's condition and the causes of its deterioration, and these findings will be used to protect the tomb for years to come."

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus