In Photos: The Life and Death of King Tut

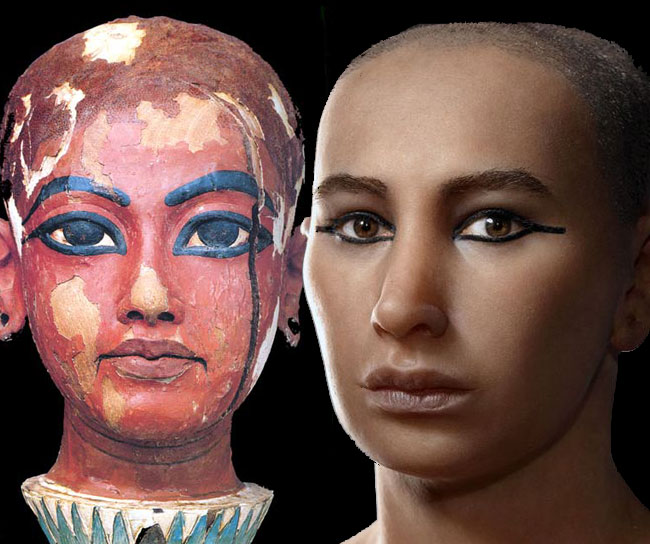

Mummy case

Tutankhamun was an Egyptian pharaoh who lived between roughly 1343 B.C. and 1323 B.C. Often called the "boy-king," he ascended the throne at around the age of 10. Today he's most famous for his tomb, which was discovered largely intact in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 by a team led by archaeologist Howard Carter.

"As my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist. Strange animals, statues of gold …" wrote Carter about his experience as he entered the tomb.

The tomb continues to deliver in the way of archaeological mysteries. For instance, archaeologists think there may be hidden chambers behind walls of the tomb and that at least one of those cavities may hold the remains of Queen Nefertiti, King Tut's stepmom and wife of Tut's father, Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. Ongoing radar scans of the tomb could uncover whether or not such cavities do exist.

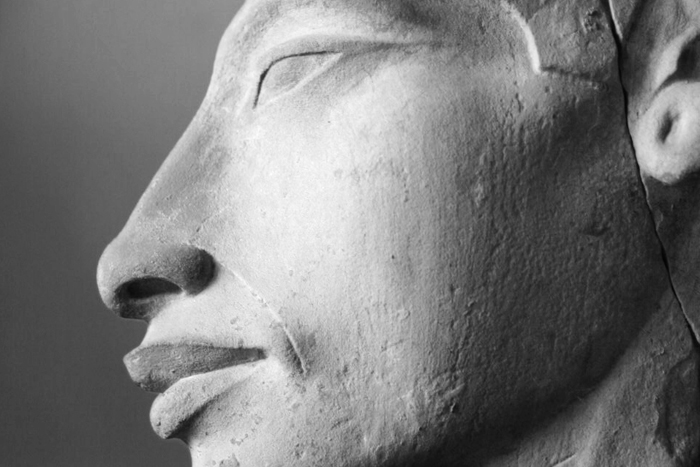

Akhenaten statue

Tutankhamun's father is believed to be the pharaoh Akhenaten. He unleashed a religious revolution that resulted in the Aten, the sun disc, becoming Egypt's main deity. Akhenaten went so far as to destroy images of other gods. Tutankhamun tried to undo his father's changes, turning Egypt's religion back to its traditional focus on multiple gods.

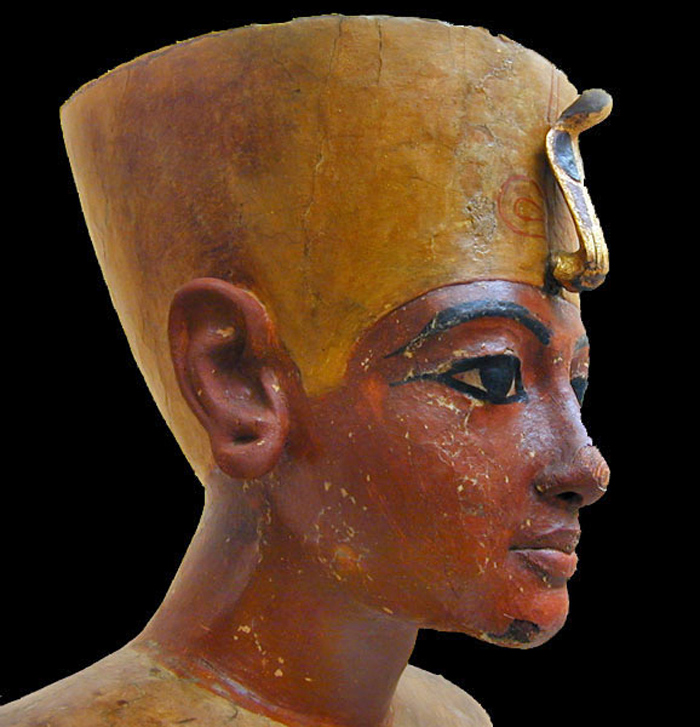

Tutankhamun bust

Now a new study, detailed in 2013 in the journal Études et Travaux, suggests that as part of this program of religious normalization Tutankhamun's mummy was prepared so that it literally appeared as the god Osiris. His penis was mummified at a 90-degree angle (recalling Osiris' fertility); his body and coffins were covered with a black goolike liquid that changed the color of the pharaoh's skin; and his heart was removed, recalling the tale of Osiris being cut apart by his brother Seth.

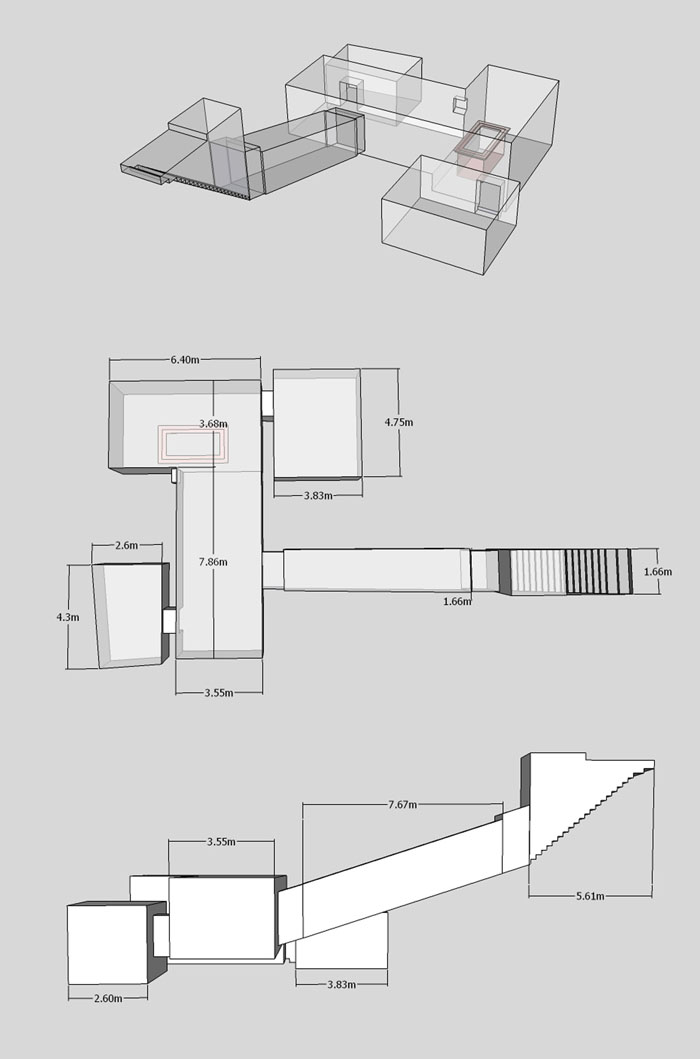

Tutankhamun's tomb

After Tutankhamun's tomb was discovered, it was given the name KV 62, following a system of naming in the Valley of the Kings. It is a relatively small four-chambered tomb that originally may not have been meant for Tutankhamun, but rather for another important royal figure named "Ay," who would later become pharaoh.

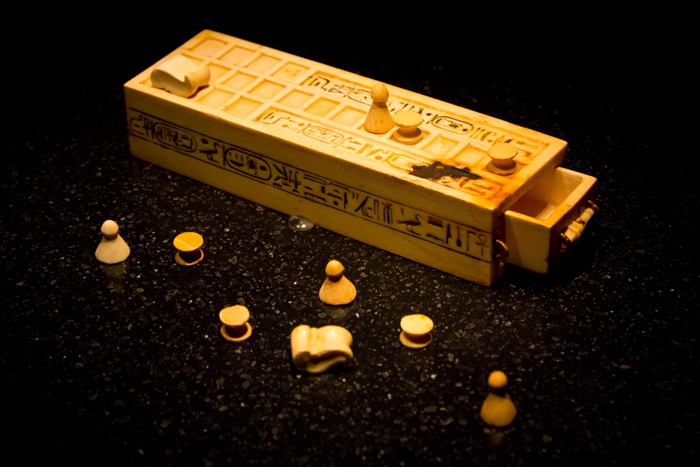

Goods for the afterlife

A wide range of goods were placed in Tutankhamun's tomb for the afterlife. They include this finely preserved "Senet" board with pieces. Senet means "game of passing," and was a popular two-player board game played throughout much of Egypt's history.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Leopard head

While performing the opening of the mouth ceremony, priests may have attached a small leopard head like this to their robes while doing so. The head, which is often shown in international exhibitions, is made of gilded wood, rock crystal and colored glass.

King Tut's shrines

Tutankhamun's burial was extremely complex and included four shrines (the outermost seen here) with his sarcophagus located within.

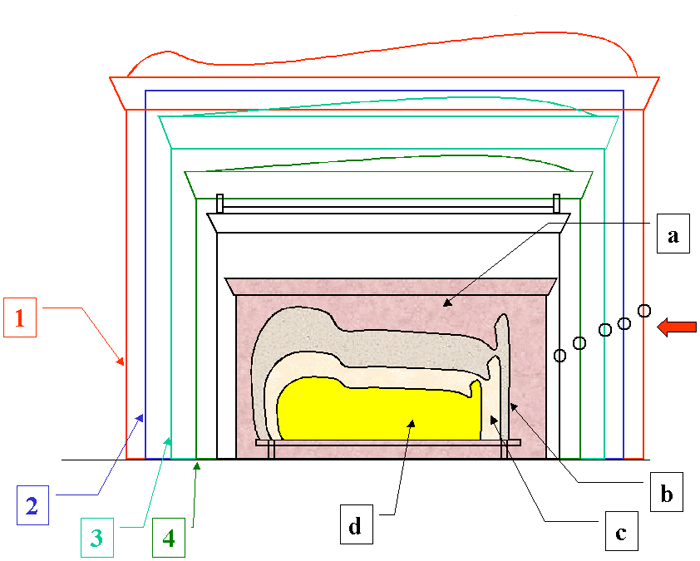

Nested sarcophagus

A diagram showing the shrines and nested sarcophagus of Tutankhamun. Gradually the containers get smaller and smaller until you reach the mummy itself.

A unique lid

Here, one of four stoppers, each of which is in the form of Tutankhamun's head. They were used on a large canopic jar, which was used to hold the pharaoh's inner organs. Recent DNA analysis suggested the pharaoh suffered from a number of illnesses that left him crippled and forced him to use a walking stick. The cause of his death is unknown, though some say he died from a fracture possibly caused by a fall from a chariot.

A well-known figure

Although Tut did not have a long reign, and his tomb was relatively small, the fact that it was found intact with magnificent treasures inside means that he is now one of the most widely known figures from the ancient world. This image shows a tiny canopic coffinette; there were also four of them and they each held one of Tut's internal organs.

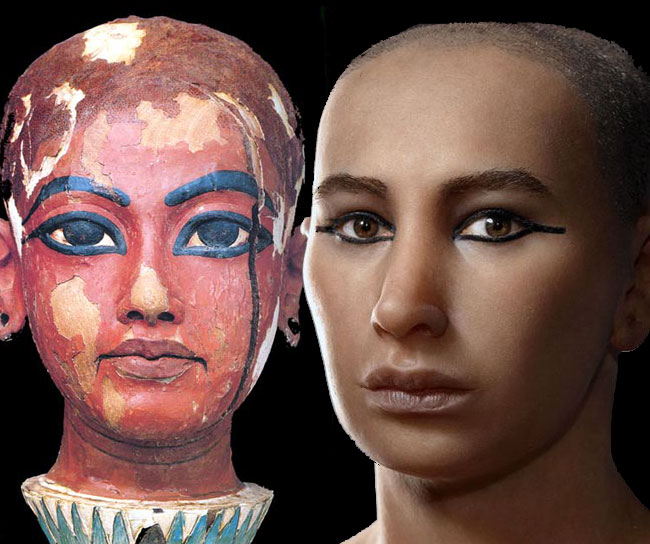

King Tut

Forensic scientists and artists completed in 2005 the first ever facial reconstructions of King Tut using CT scans of his mummifiedremains. The pharaoh's reconstructed facial composition turned out to bestrikingly similar to ancient portraits of Tut.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.