Earth's Gravitational Pull Cracks Open the Moon

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Earth's gravitational pull is massaging the moon, opening up faults in the lunar crust, researchers say.

Just as the moon's gravitational pull causes seas and lakes to rise and fall as tides on Earth, the Earth exerts tidal forces on the moon. Scientists have known this for a while, but now they've found that Earth's pull actually opens up faults on the moon.

"We know the close relationship between the Earth and the moon goes back to their origins, but what a surprise [it was] to find the Earth is still helping to shape the moon," study lead author Thomas Watters, a planetary scientist at the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., told Space.com. [The Moon: 10 Surprising Lunar Facts]

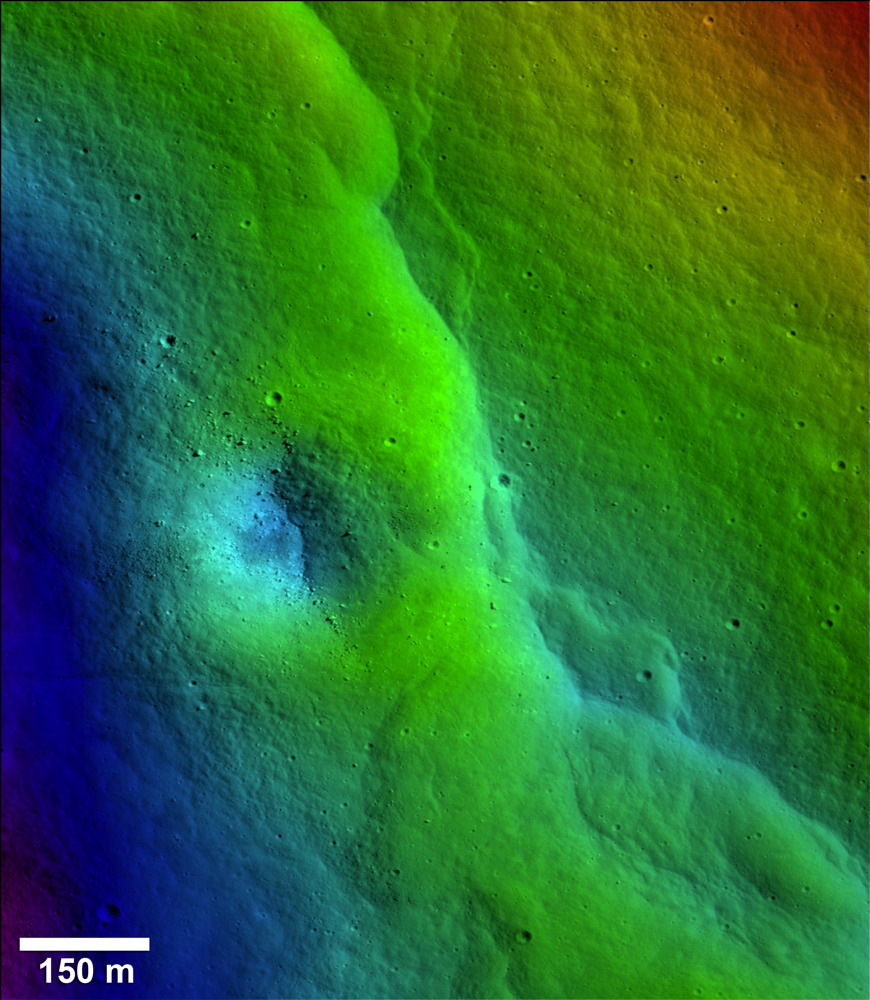

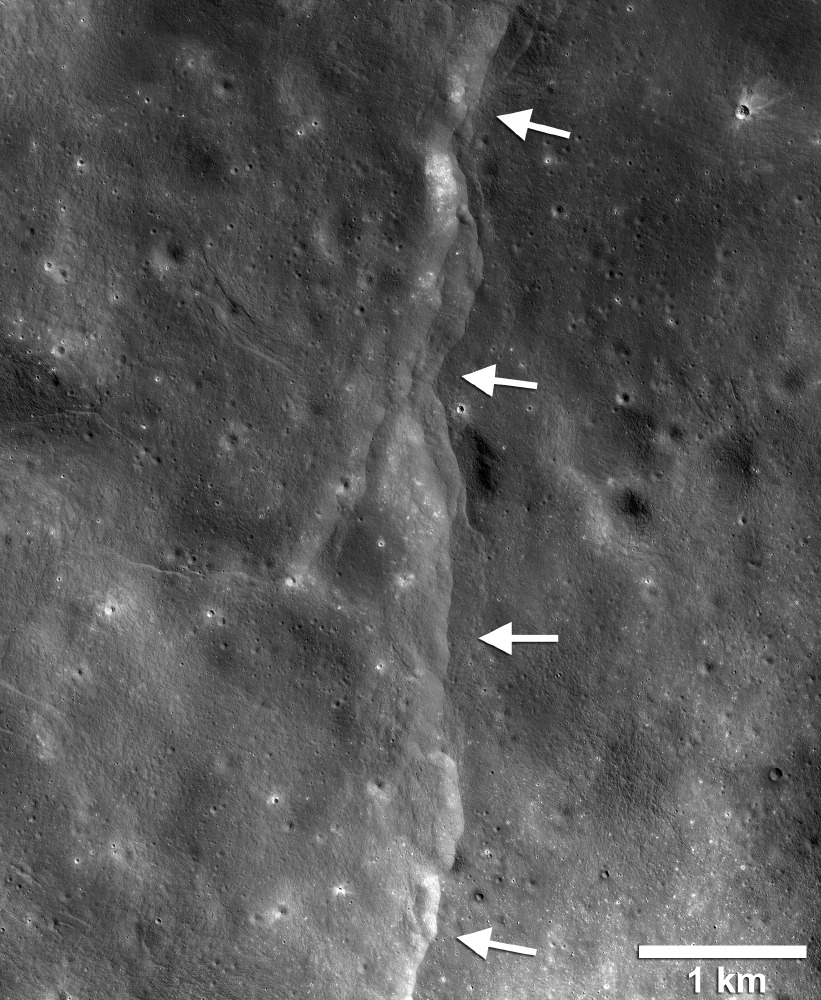

The researchers analyzed data from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which launched in 2009. In 2010, the spacecraft helped scientists discover that the moon is shrinking: High-resolution LRO images revealed 14 lobe-shaped fault scarps, or cliffs, which likely formed as the hot interior of the moon cooled and contracted, forcing the solid crust to buckle.

After more than six years in orbit and imaging nearly three-quarters of the moon's surface, LRO has detected more than 3,200 of these fault scarps. These cliffs are the most common tectonic feature on the moon, and are typically dozens of yards or meters high and less than about 6 miles (10 kilometers) long. Previous research had suggested they were less than 50 million years old, and are likely still actively forming today.

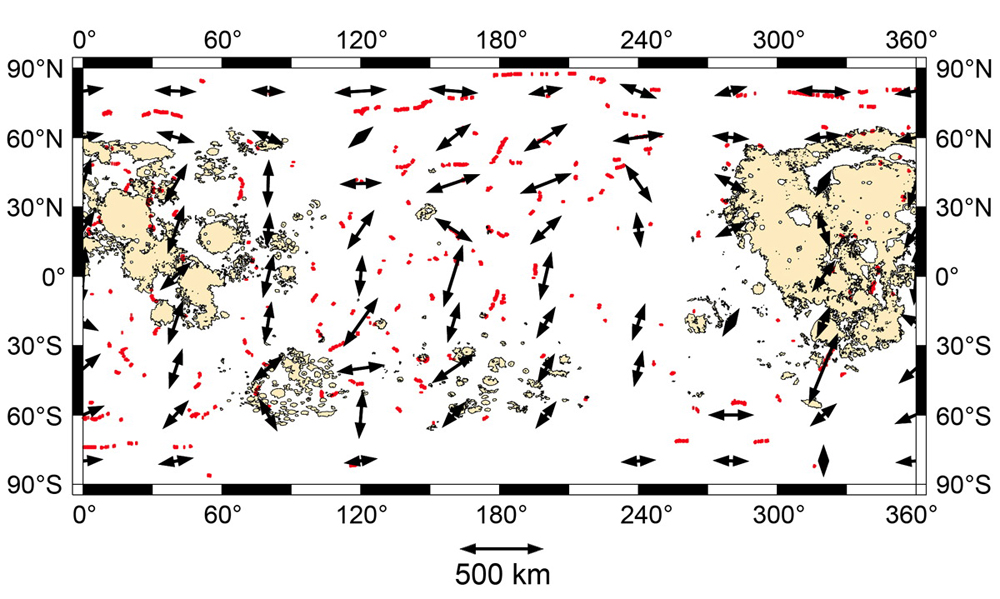

If the only influence on lunar fault scarp formation was the cooling of the moon's interior, the orientations of these cliffs should be random, because the forces of contraction would be equal in strength in all directions, researchers said.

"It was a big surprise to find that the fault scarps don't have random orientations," Watters said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Instead, "there is a pattern in the orientations of the thousands of faults, and it suggests something else is influencing their formation, something that's also acting on a global scale," Watters said in a statement. "That something is the Earth's gravitational pull."

Earth's tidal forces do not act equally across the surface of the entire moon. Instead, they act most strongly on the parts of the moon that are either closest to or farthest away from Earth. The result is that many scarps are lined up north to south at low and mid latitudes near the moon's equator and east to west at high latitudes near the moon's poles.

The effects of Earth's tidal forces are likely about 50 to 100 times smaller than those from the moon's contraction, Watters said. A model incorporating the effects of tidal and contractional forces on the moon's surface closely matched the fault scarps observed on the moon, he added.

"With LRO, we've been able to study the moon globally in detail not yet possible with any other body in the solar system beyond Earth, and the LRO data set enables us to tease out subtle but important processes that would otherwise remain hidden," John Keller, LRO project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a different statement.

If these lunar faults are still active, shallow "moonquakes" might occur along them. These rumbles should happen most often when Earth's tidal effects are greatest on the moon — when the moon is farthest away from the Earth in its orbit. A network of seismometers on the moon's surface could one day detect these quakes, Watters said.

Watters and his colleaguesdetailed their findings in the October issue of the journal Geology.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus