Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

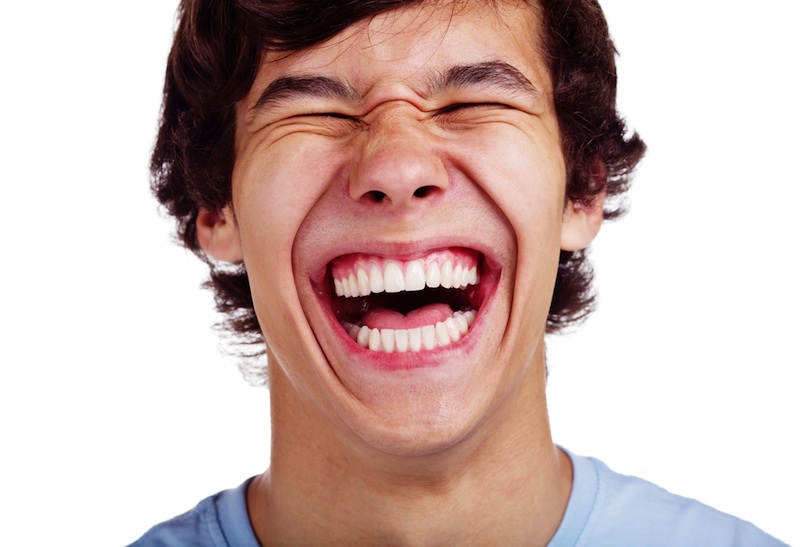

Do you crack up at the slightest hint of a joke? Or do you keep a poker face when Uncle Herbert trots out his tired comedy routine?

It turns out, whether you're quick to laugh and smile may be partly in the genes.

"One of these big mysteries is why do some people laugh a lot, and smile a lot, and other people keep their cool," said study co-author Claudia Haase, a psychology researcher at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. "Culture plays a role in it, and personality plays a role in it — and our study shows that DNA also plays a role in how strongly we react when we see something funny."

The gene was previously tied to depression and other negative states, but the new study suggests it may be linked to people experiencing more emotional highs and lows, Haase added. [10 Surprising Facts About the Brain]

Serotonin and the brain

The brain chemical serotonin moderates mood, appetite and desire. Some brain and nerve cells communicate by releasing serotonin into the gaps between two brain cells, and serotonin circulates until a protein sitting on the cell membrane, called a serotonin transporter, pulls the chemical back into the cell, said Dr. Keith Young, a professor of psychiatry at the Texas A&M Health Science Center and a researcher at the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System, in Temple, Texas.

A few decades ago, scientists discovered the most common antidepressants, called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), blocked serotonin transporters, said Young, who was not involved in the current study. Scientists began looking for genes related to the transporter, to see if these genes played a role in psychological disorders.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the 1990s, researchers zeroed in on a gene called 5HTTLPR, which affects how many copies of the serotonin transporter the body makes. People inherit two copies — one from each parent — and there are two variants: a long and a short allele, or version, of the gene. Over the past two decades, several studies tied the short allele to a host of negative emotions, from major depression to post-traumatic stress disorder and to embarrassment in socially awkward situations, the researchers said.

Laughing matter

But, scientists wondered, if the gene version were detrimental, then why would so many people have it?

For instance, in the current study, about 7 out of 10 people had at least one copy of the short allele.

That made Haase and her colleagues wonder whether the gene played a role in both positive and negative emotions. The researchers analyzed video data from three experiments: one in which people looked at cartoons from The New Yorker and "The Far Side," one in which the people watched a clip from the absurdist movie "Stranger than Paradise," and one in which married couples talked out a disagreement. All of the participants provided saliva to test their genetic makeup.

The research team then coded the facial expressions people made, distinguishing fake or polite smiles and laughs from the real thing. (Real smiles and laughs crinkle the muscles around the eye a certain way, Haase said).

People with two copies of the short allele laughed and smiled the most; those with one short and one long copy were in the middle, and those with two long versions of the gene smiled and laughed the least, stated the study, which was published online on Monday (June 1) in the journal Emotion.

"People with the short allele have higher highs, and they also have lower lows. They kind of have amplified emotional reactions," Haase told Live Science.

The new finds suggest the short version of the gene makes people more sensitive, to the both good and the bad in their lives, Haase said.

For instance, a few small studies have shown that people with two copies of the short version of the 5HTTLPR gene "really flourish in positive marriages, and they really wither in negative emotional environments," Haase said.

The findings also tie nicely with Young's work, which found that people with two copies of the short allele tended to have larger brain volumes in a region called the thalamus, which helps generate emotions, Young said.

"It makes perfect sense that people with short alleles have an increase in both positive and negative emotional thinking," because the brain regions responsible for emotional processing may actually be bigger in these individuals, Young told Live Science.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus