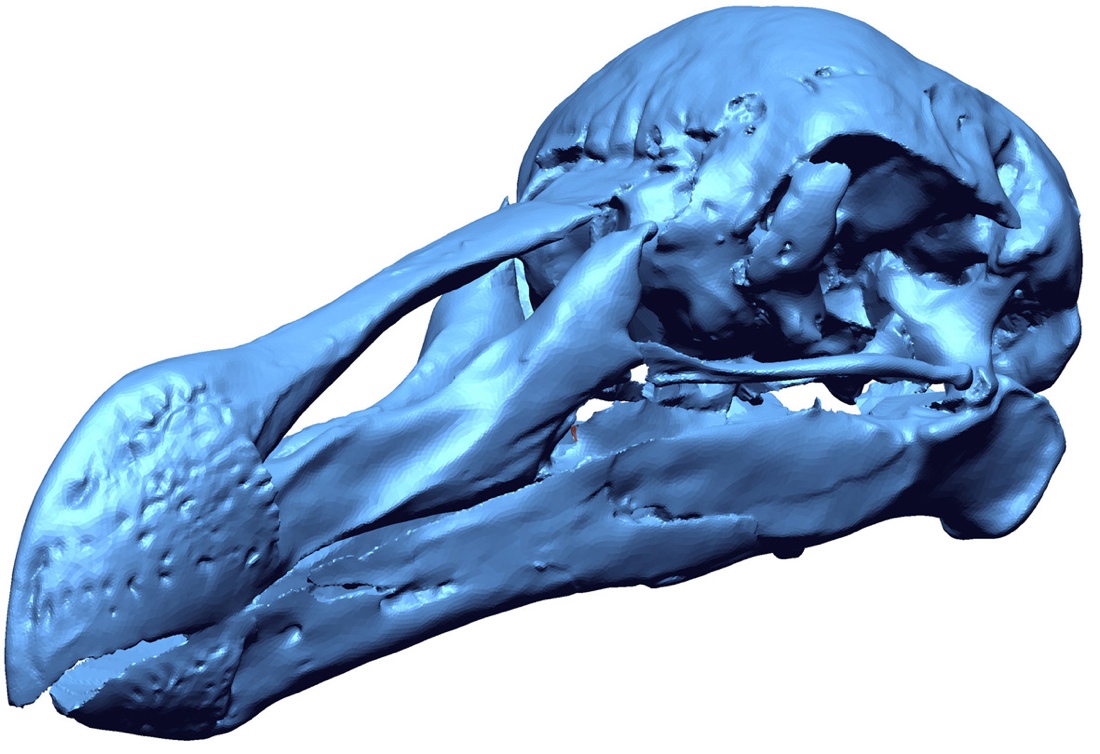

Dodo Bird Skeleton Reveals Long-Lost Secrets in 3D Scan

New laser scans of the dodo, perhaps the most famous animal to have gone extinct in human history, have unexpectedly exposed portions of its anatomy unknown to science, which are revealing secrets about how the bird once lived.

The dodo was a flightless bird about 3 feet (1 meter) tall that was native to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. It went extinct by 1693, less than a century after the Dutch discovered the island in 1598, killed off by creatures such as rats and pigs, which sailors introduced to Mauritius either accidentally or intentionally.

The giant bird was actually a type of pigeon. "The skull of the dodo is so large and its beak so robust that it is easy to understand that the earliest naturalists thought it was related to vultures and other birds of prey, rather than the pigeon family," said study co-author Hanneke Meijer at the Catalan Institute of Paleontology in Spain.

Surprisingly, despite the dodo's fame, and the fact the bird was alive during recorded human history, little is known about the anatomy and biology of this animal. "The dodo's extinction happened at a time when people didn't understand the concept of extinction — science as we know it was still in its infancy,"lead study author Leon Claessens, a vertebrate paleontologist at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, told Live Science. "This meant that nobody tried to make a collection of the bird or study it in detail." [Wipe Out! History's 7 Most Mysterious Extinctions]

To shed new light on the dodo, Claessens and his colleagues went to the Natural History Museum in Port Louis, Mauritius, to investigate the only known complete skeleton from a single dodo. All other dodo skeletons are composites of several birds.

Amateur naturalist and barber Etienne Thirioux found the specimen the researchers analyzed near Le Pouce Mountain on Mauritius in about 1903. It was unstudied by scientists until now.

The scientists used a laser scanner to create a 3D digital model of the specimen. In addition, they scanned a second dodo skeleton Thirioux also created, a composite of two or more skeletons that was housed at the Durban Museum of Natural Science in South Africa.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We discovered that the anatomy of the dodo we were looking at was not previously described in detail," Claessens said. "There were bones of the dodo that were just unknown to science until now."

These skeletons contained previously unknown bones of the dodo, such as its kneecaps. The complete specimen also preserved the original skeletal proportions of the dodo that composites made of several birds did not. [See Images of the Dodo Bird Skeletons and Laser Scans]

"The 3D laser surface scans we made of the fragile Thirioux dodo skeletons enabled us to reconstruct how the dodo walked, moved and lived to a level of detail that has never been possible before," Claessens said. "There are so many outstanding questions about the dodo bird that we can answer with this new knowledge."

For instance, by discovering new dodo knee and ankle bones, "we can learn a lot about how it moved," Claessens said. "It will make a tremendous difference in calculations of the muscle force the dodo could have generated."

The researchers also found that the dodo's breastbone, or sternum, lacked a keel, unlike the Rodrigues solitaire, a closely related extinct flightless pigeon that was known to have used its wings in combat. This suggests that dodos fought each other less than Rodrigues solitaires fight each other.

The smaller ancestors of the dodo must have flown to Mauritius no more than 8 million years ago, when geologists suggest the volcanic island was born. Animals on islands often grow to gigantic sizes when they do not face the same competition as they do on the mainland.

"The dodo must have experienced a fourfold increase in body mass compared to its ancestors, if not an eightfold increase," Claessens said. "If that happened in 8 million years or less, that's a rapid increase. It raises the question of how the dodo would have continued to evolve if it weren't for humans."

"The history of the dodo provides an important case study of the effects of human disturbance of the ecosystem, from which there is still much to learn that can inform modern conservation efforts for today's endangered animals," Claessens added.

In the future, the researchers "will investigate how the jaw muscles in the dodo's amazingly robust skull might have worked," Claessens said. "My best guess is that it was eating tremendously hard seeds, but who knows, maybe it was eating crabs."

The scientists detailed their findings today (Nov. 6) at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Berlin.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.