'Our hearts stopped': Scientists find baby pterosaurs died in violent Jurassic storm 150 million years ago

Researchers found storm injuries during a baby pterosaur post-mortem, solving a Jurassic mystery that was 150 million years in the making.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A stunning fossil find has revealed two baby pterosaurs that were struck down mid-flight in a "catastrophic" tropical storm 150 million years ago.

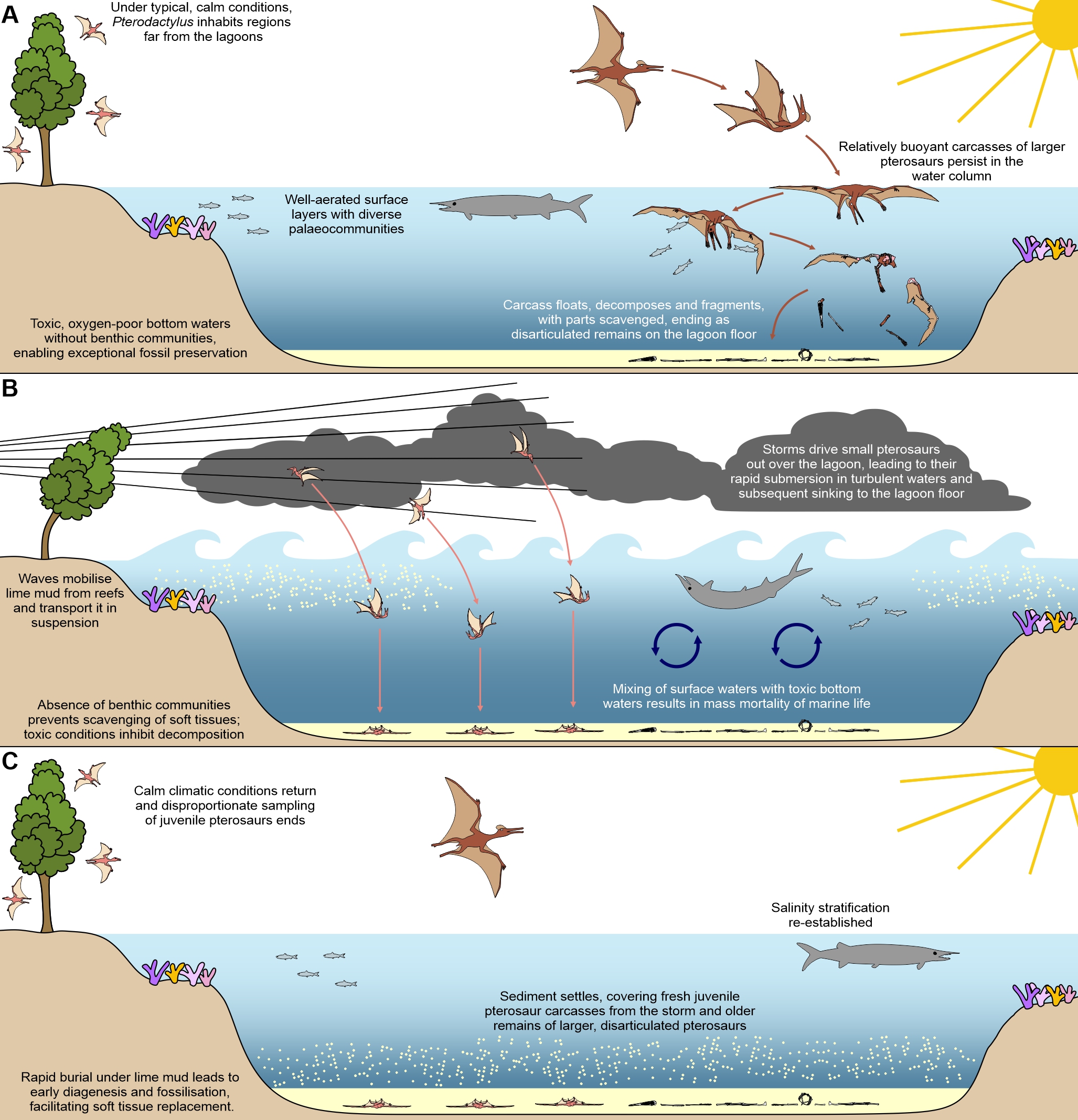

Researchers carried out an animal post-mortem (necropsy) on two Jurassic pterosaur skeletons from Germany and concluded that violent winds likely drove the flying reptiles into a lagoon, where they drowned under the stormy waves.

Pterosaurs, informally called "pterodactyls," ruled the skies during the age of dinosaurs. The fossilized skeletons documented in the new study belonged to the first pterosaur species ever discovered, Pterodactylus antiquus, which spawned the pterodactyl nickname.

The newborns are two of the smallest P. antiquus specimens ever discovered, with a wingspan of about 8 inches (20 centimeters) — around the size of a small bat. The researchers' analysis of these fossils, published Sept. 5 in the journal Current Biology, suggests that they were probably two of many baby pterosaurs that died in storm-related mass mortality events in the region. Adult P. antiquus had an estimated wingspan of around 3.5 feet (1.1 meters), meaning it likely had a better shot at resisting the winds that doomed the youngsters.

The baby pterosaurs are nicknamed "Lucky" and "Lucky II," according to a statement released by the researchers. While they may have been unlucky to perish in a storm, scientists were lucky that their dainty and delicate skeletons were discovered.

"Pterosaurs had incredibly lightweight skeletons," study lead author Rab Smyth, who conducted the research as part of his doctoral studies at the University of Leicester in the U.K., said in the statement. "Hollow, thin-walled bones are ideal for flight but terrible for fossilisation. The odds of preserving one are already slim and finding a fossil that tells you how the animal died is even rarer."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The pterosaurs were preserved in the Upper Jurassic Solnhofen platy limestone rock formation, which is about 153 million to 148 million years old and located in Bavaria, southern Germany. Paleontologists have found hundreds of pterosaurs in this formation, which was once a semi-tropical seascape with coral reefs and small islands, according to the study.

Solnhofen's fossils are often well-preserved young pterosaurs, while larger adults are rarer and typically fragmented. This is unusual, given that larger and more robust bones often have a better chance of sticking around in an environment and becoming fossils.

Study co-author David Unwin, a palaeontologist at the University of Leicester, said that the team was very excited when Smyth came across Lucky in the Bergér Museum in Harthof but thought it was a one-off. Then, a year later, Smyth came across Lucky II — currently on display in the Burgermeister Müller in Solnhofen, but owned by the Bavarian State Collection for Palaeontology and Geology in Munich. The researchers examined the fossil with a fluorescent UV torch and saw Lucky II had suffered a telling fracture on its arm (part of its wing) before death.

"It literally leapt out of the rock at us — and our hearts stopped," Unwin said in the statement. "Neither of us will ever forget that moment."

Both Lucky and Lucky II had humeral fractures consistent with excessive wind force during flight, similar to those experienced by birds and bats during severe storms today. The researchers believe that violent gusts of wind swept the young pterosaurs away from the safety of land and forced them into the lagoon. Storm-fueled currents then quickly forced them down into the depths of the water column and buried their bodies in sediment, according to the study.

By studying the two baby pterosaurs, alongside data collected from more than 40 other Pterodactylus individuals, the team concluded that Solnhofen has so many small pterosaurs because of catastrophic mass mortality events like these storms that larger individuals would have been able to resist.

"For centuries, scientists believed that the Solnhofen lagoon ecosystems were dominated by small pterosaurs," Smyth said. "But we now know this view is deeply biased. Many of these pterosaurs weren't native to the lagoon at all. Most are inexperienced juveniles that were likely living on nearby islands that were unfortunately caught up in powerful storms."

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus