'So weird': Ankylosaur with 3-foot spikes sticking out of its neck discovered in Morocco

The ostentatious spikes of a newly described ankylosaur fossil suggest that its armor evolved via sexual selection.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A fossil ankylosaur discovered in the mountains of Morocco in 2023 was adorned with some of the most frightening armor ever seen.

Researchers suggest that this intimidating array of spikes was sexually selected — like a peacock's tail, it originally evolved to attract mates, rather than to deter predators. By supporting this cumbersome display, the dinosaur, named Spicomellus afer, demonstrated that it was a healthy and worthy partner.

A study analyzing the fossilized remains of the S. afer specimen, which dates to the Middle Jurassic (174.7 to 161.5 million years ago), was published Wednesday (Aug. 27) in the journal Nature.

An earlier rib fragment with fused spikes discovered in 2021, also from Morocco, offered the first evidence of this bizarre species.

"It was so weird that the first thing we did was a CT scan to check that it wasn't fake and that somebody hadn't stuck spines onto the top of the ring," lead author Susannah Maidment, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London, told Live Science. It was in fact real, so she and her team traced the site where it had been found, leading to the 2023 discovery in the Middle Atlas Mountains near Boulemane.

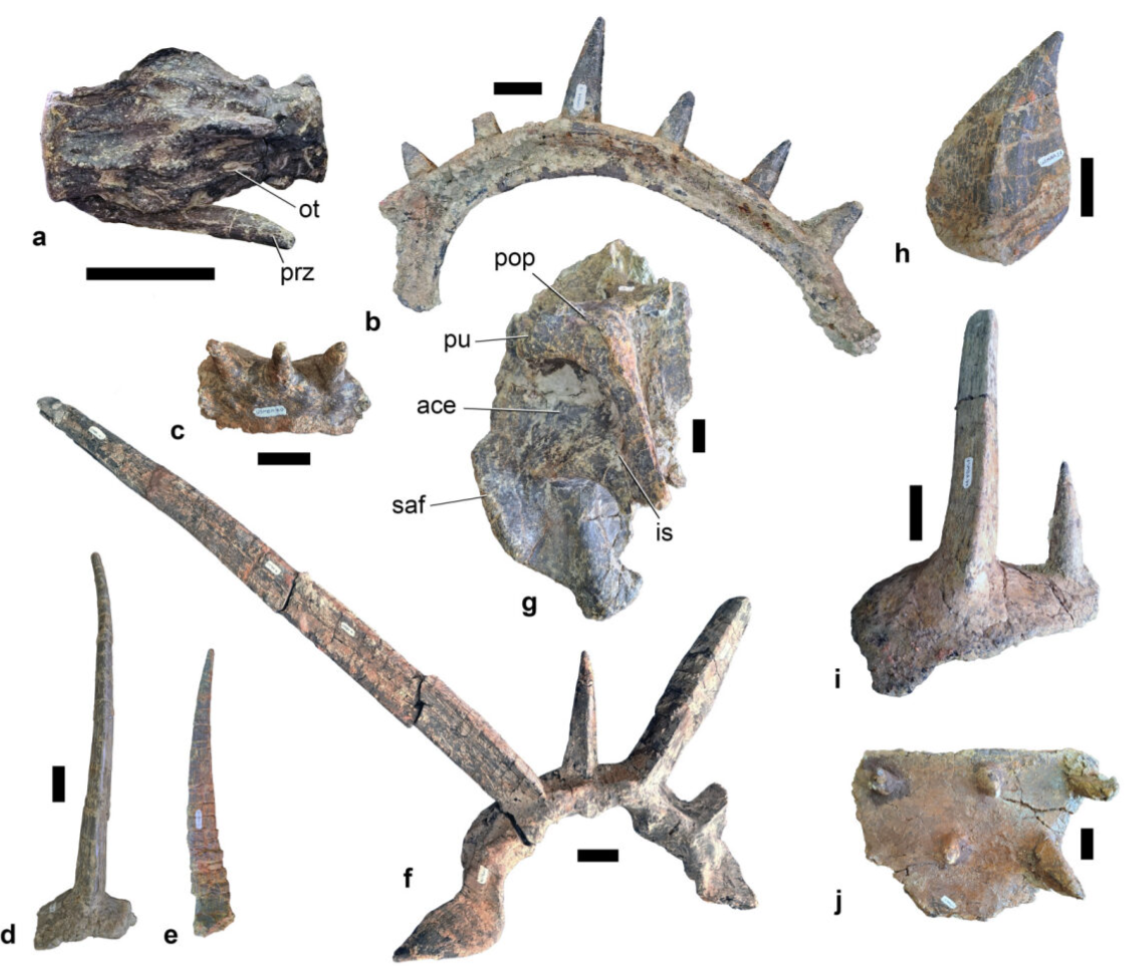

Analysis of the new fossil material confirms that S. afer is the earliest known ankylosaur. The specimen comprises vertebral and rib fragments, parts of the pelvis, and osteoderms — bony deposits in the skin seen in modern reptiles such as crocodiles and alligators.

The fossil assemblage helped the authors to reconstruct how the animal may have looked in life. The low-slung, turtle-shaped animal was approximately 13 feet (4 meters) long, according to Maidment. She noted that the skeleton is not complete and that these measurements are likely inexact.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Long spikes extended from osteoderms on its neck, ringing its head in a fantastical array.

"Ankylosaurs have bony collars around their necks but they're normally a series of flat plates that are fused together and just sit around the neck," Maidment said. "This one had a huge, robust, bony collar the shape of the neck with an enormous pair of meter-long spikes sticking out either side."

The longest of the 10 cervical spikes, extending from either side of the neck, reached at least 34 inches (87 centimeters). Additional spikes stuck out from each rib and were actually part of the skeleton.

"When we see features among living animals that are very hypertrophied and seem to have no function — and would be annoying to carry around — they are related to sex in some way or another," Maidment said.

Still, the researchers suggest that these spikes may have served a secondary, defensive purpose.

They speculate that the end of the tail featured a mace-like array. One of the blade-like spines discovered by the researchers was 17 inches (42 cm) long, and was unlikely to have been attached to any other part of the body.

The tail vertebrae that supported this fearsome armature indicate that the mechanisms for the defensive clubs of Cretaceous ankylosaurs were well underway early in the evolution of this group of dinosaurs. "Handle vertebrae" (closely linked bones with no cartilage between them) helped to stabilize the bony appendages for which later ankylosaurs are known.

The fact that S. afer featured similar bones indicates that its armor was not purely decorative — its tail deterred predators too.

Among ankylosaurs, function may have actually followed fashion. The ankylosaurs of the Cretaceous featured much simpler armor that was almost certainly a defense against a growing range of theropod dinosaurs, crocodilians, snakes and mammals that would have seen them as appealing prey.

Richard Pallardy is a freelance science writer based in Chicago. He has written for such publications as National Geographic, Science Magazine, New Scientist, and Discover Magazine.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus