In Photos: The Famous Flightless Dodo Bird

Perhaps the most famous extinction in human history was that of the flightless dodo bird. Many mysteries remain about the bird, its life and death. Now, new laser-scanning and an examination of a dodo skeleton collected more than 100 years ago are revealing new anatomy of the bird and secrets of its lifestyle. Here are images of the dodo bird and laser scans of its skeleton. [Read full story on the dodo bird's skeleton]

Painting a bird

The dodo was a flightless bird native to the isle of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. It went extinct by 1693, less than 100 years after the Dutch discovered Mauritius in 1598. The bird, related to pigeons, was about 3 feet (1 meter) tall, was killed off by animals such as rats and pigs that were introduced to the island, either accidentally or intentionally. Here, George Dante paints a model of a dodo bird. Dante worked with Phil Fraley Productions to recreate the extinct flightless bird, commissioned in 2005 for a museum in Singapore. (Image Credit: George Dante)

Fat or thin?

It's hard to say exactly what the dodo bird would have looked like when alive, as before cameras artists painted newly discovered animals. Such artists seem to have been more interested in "depicting plump or colourful animals than recording their true likeness," according to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Many people did, however, think the dodo bird was a plump animal, the museum said. However, measurements of a dodo specimen at the Oxford museum and other dodo bones suggest otherwise, revealing a much slimmer bird. Here, a reconstruction of the dodo bird. (Image Credit: Dreamstime.com)

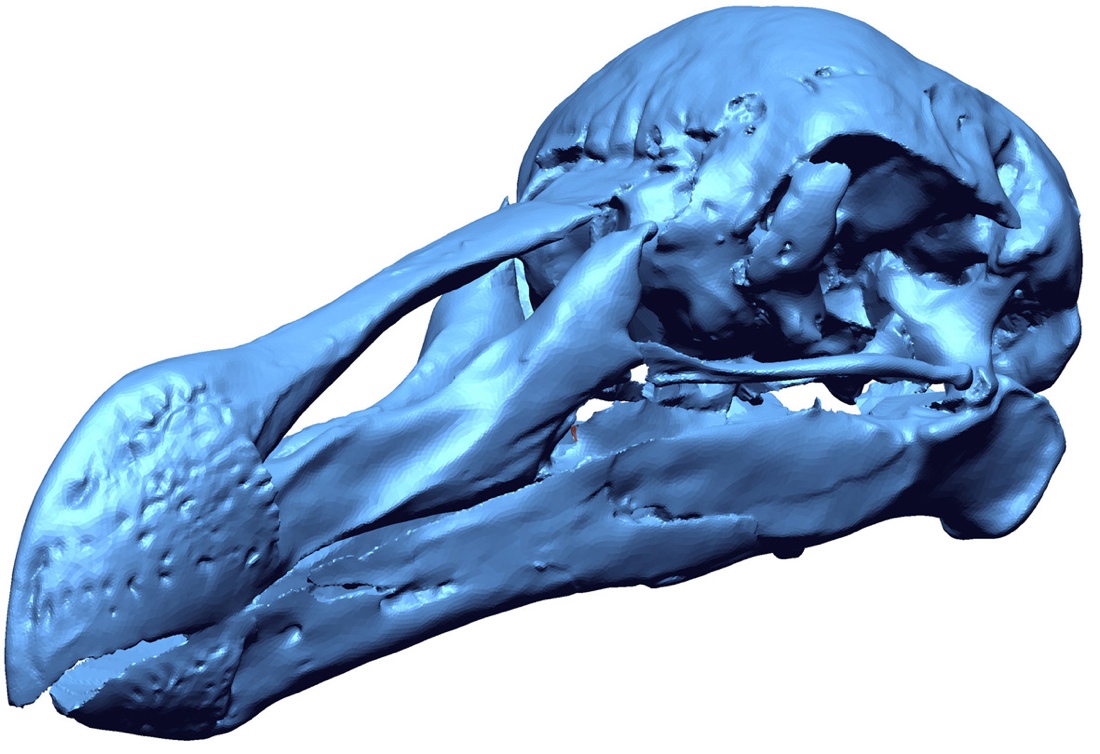

Dodo skull

To shed new light on the mysterious bird, for which scientists have many outstanding questions, Leon Claessens, a vertebrate paleontologist at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and colleagues laser-scanned the Port Louis skeleton, and created a digital model of it. Here, a 3D digital model of the skull of the only complete skeleton of a single dodo, found in 1903 on Mauritius. The dodo had an extremely robust jaw and the researchers hope to investigate how the jaw muscles may have worked. "My best guess is that it was eating tremendously hard seeds, but who knows, maybe it was eating crabs," Claessens said. (Image Credit: Leon Claessens and Mauritius Museums Council)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Complete skeleton

The only known complete skeleton belonging to an individual dodo was discovered in about 1903 by amateur naturalist and barber Etienne Thirioux. He found the skeleton near Le Pouce Mountain on the island of Mauritius. Here, a 3D digital model created with laser scanning of the so-called Port Louis dodo skeleton. (Image Credit: Leon Claessens and Mauritius Museums Council)

No sternum?

Here, researcher Andy Biedlingmaier scans the only known complete skeleton from a single dodo. From the scans, the researchers discovered that unlike a closely related extinct flightless pigeon, called the unlike the Rodrigues solitaire, the dodo didn't have a keel on its breastbone (or sternum). The Rodrigues pigeon was known to have used its wings in combat; as such the researchers speculate the dodos fought each other less often than the Rodrigues solitaires did. (Image Credit: Leon Claessens and Mauritius Museums Council)

A composite

In addition to scanning the complete skeleton, the researchers also laser-scanned a composite dodo skeleton that Thirioux had also created; this one was a composite of two or more skeletons housed at the Durban Museum of Natural Science in South Africa. (Image Credit: Leon Claessens and Durban Natural Science Museum)

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus