Mysterious 160 million-year-old creature unearthed on Isle of Skye is part lizard, part snake

Researchers have discovered a mysterious ancient lizard with snake-like teeth in Scotland. Breugnathair elgolensis is one of the oldest relatively complete lizard fossils and helps scientists better understand the origins of snakes in the Jurassic period.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The fossilized skeleton of a Jurassic reptile that appears to be part lizard, part snake, has been unearthed on Scotland's Isle of Skye.

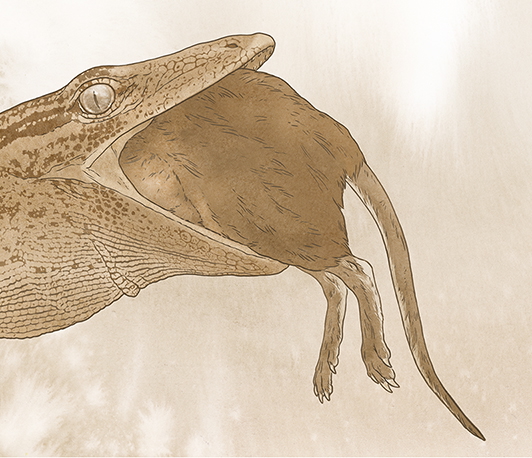

This mysterious lizard had hooked, snake-like teeth for hunting down prey 167 million years ago, a new study has found.

The newly discovered species is named Breugnathair elgolensis, which means "false snake of Elgol," honoring the creature's confusing anatomy and the Elgol area of southern Skye, where the fossil was found, according to the study published Wednesday (Oct.1) in the journal Nature.

B. elgolensis was only about 16 inches (41 centimeters) long, but that still made it one of the largest lizards in its ecosystem, according to a statement released by the researchers. Scientists suspect that it hunted smaller lizards, early mammals and even young dinosaurs, such as small herbivorous heterodontosaurids and predatory bird-like paravians.

It had a snake-like jaw and curved teeth similar to a modern python, but its body was short, with fully formed limbs like a lizard. B. elgolensis also had gecko-like features on some of its bones, including the back of its skull. Researchers are still deciphering B. elgolensis' evolutionary history, but its discovery could change the way they look at early snake evolution.

Related: Night lizards survived dinosaur-killing asteroid strike, despite being close enough to see it happen

Scientists currently have a scattered understanding of early lizard and snake evolution. Both animals belong to a group called Squamata, which emerged about 190 million years ago. There's some overlap between members of the group, but lizards came first and generally have four limbs, while snakes are limbless.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The Jurassic fossil deposits on the Isle of Skye are of world importance for our understanding of the early evolution of many living groups, including lizards, which were beginning their diversification at around this time," study co-lead author Susan Evans, a professor of vertebrate morphology and paleontology at the University College London, said in the statement.

Study co-author Stig Walsh, a senior curator of vertebrate paleobiology at the National Museums Scotland, first uncovered the B. elgolensis fossil in 2015. The team has since spent nearly a decade preparing and studying the specimen, which has included subjecting it to high-powered X-rays and detailed computed tomography (CT) imaging scans.

The researchers determined that B. elgolensis belonged to a Squamata sub-group called Parviraptoridae, which was previously only known from fragments of other fossils. While snake-like bones had been found in close proximity to gecko-like bones, some scientists had assumed they came from two separate animals. The new fossil confirms that one species did indeed have both features, according to the statement.

"I first described parviraptorids some 30 years ago based on more fragmentary material, so it's a bit like finding the top of the jigsaw box many years after you puzzled out the original picture from a handful of pieces," Evans said. "The mosaic of primitive and specialized features we find in parviraptorids, as demonstrated by this new specimen, is an important reminder that evolutionary paths can be unpredictable."

The researchers still aren't sure whether snakes evolved from species like B. elgolensis or whether snakes independently evolved similar mouth parts. It's also possible that B. elgolensis is a stem lineage within Squamata, helping to give rise to all lizards and snakes.

"This fossil gets us quite far, but it doesn't get us all of the way," study lead author Roger Benson, the Macaulay Curator at the American Museum of Natural History's Division of Paleontology, said in the statement. "However, it makes us even more excited about the possibility of figuring out where snakes come from."

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus