Mammoth RNA sequenced for the first time, marking a giant leap toward understanding prehistoric life

Scientists successfully sequence the RNA from woolly mammoths found in Siberia that lived up between 10,000 thousand and 50,000 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For the first time, scientists have successfully sequenced woolly mammoth RNA, shattering the assumption that this fragile genetic molecule couldn't survive from so long ago.

RNA, or ribonucleic acid, carries instructions between DNA and an organism's protein-building machinery, acting as a messenger to turn genetic information into proteins. RNA can reveal which genes are active in a cell at a given moment, as well as how gene-activity patterns within a cell change over time. Thus, ancient RNA can inform scientists about the cellular states of extinct species.

Although the technology behind ancient DNA research has surged over the past 20 years, ancient RNA research has seen few successes. This is due in part to its construction, as DNA molecules are double-stranded and therefore sturdier than the single-stranded RNA.

While DNA offers the blueprint of an organism, there are limits to the information it reveals. RNA "opens a window into how" that blueprint is implemented within each cell of the organism, said study co-author Zoé Pochon, a doctoral student at Stockholm University.

The aptly-named messenger RNA (mRNA) "is DNA's messenger," she told Live Science in an email. "In other words, it carries working copies of DNA instructions from the nucleus to the cell." Other parts of the cell then follow these instructions, she added.

In the new study, published Friday (Nov. 14) in the journal Cell, the researchers turned to 10 well-preserved woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenus) specimens from Siberia that dated to 10,000 to 50,000 years. The team hoped that the frozen conditions had preserved more of the specimens and so would produce better results.

One specimen in particular — Yuka, a ginger-colored juvenile mammoth — yielded spectacular results. Yuka is about 39,000 years old, making this the oldest RNA sequenced to date. Previously, that distinction was held by tissues sampled from a canid dated to approximately 14,300 years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Remarkably, the scientists found definite genetic signals that Yuka, previously believed to be a female based on its physical attributes, is actually a male.

Additionally, the RNA offered insights into Yuka's muscle function — specifically, the RNA "creating the proteins that are stretching and contracting the muscles," said study lead author Emilio Mármol Sánchez, who was working at the Center for Evolutionary Hologenomics, University of Copenhagen at the time of the paper. The team "also found a whole set of regulatory genes,' he told Live Science.

When cells die, what is left behind is the last function of the RNA. "What we are capturing here is, in a sense, a snapshot of the last moments of the life of these mammoths" within their cells, Mármol Sánchez said.

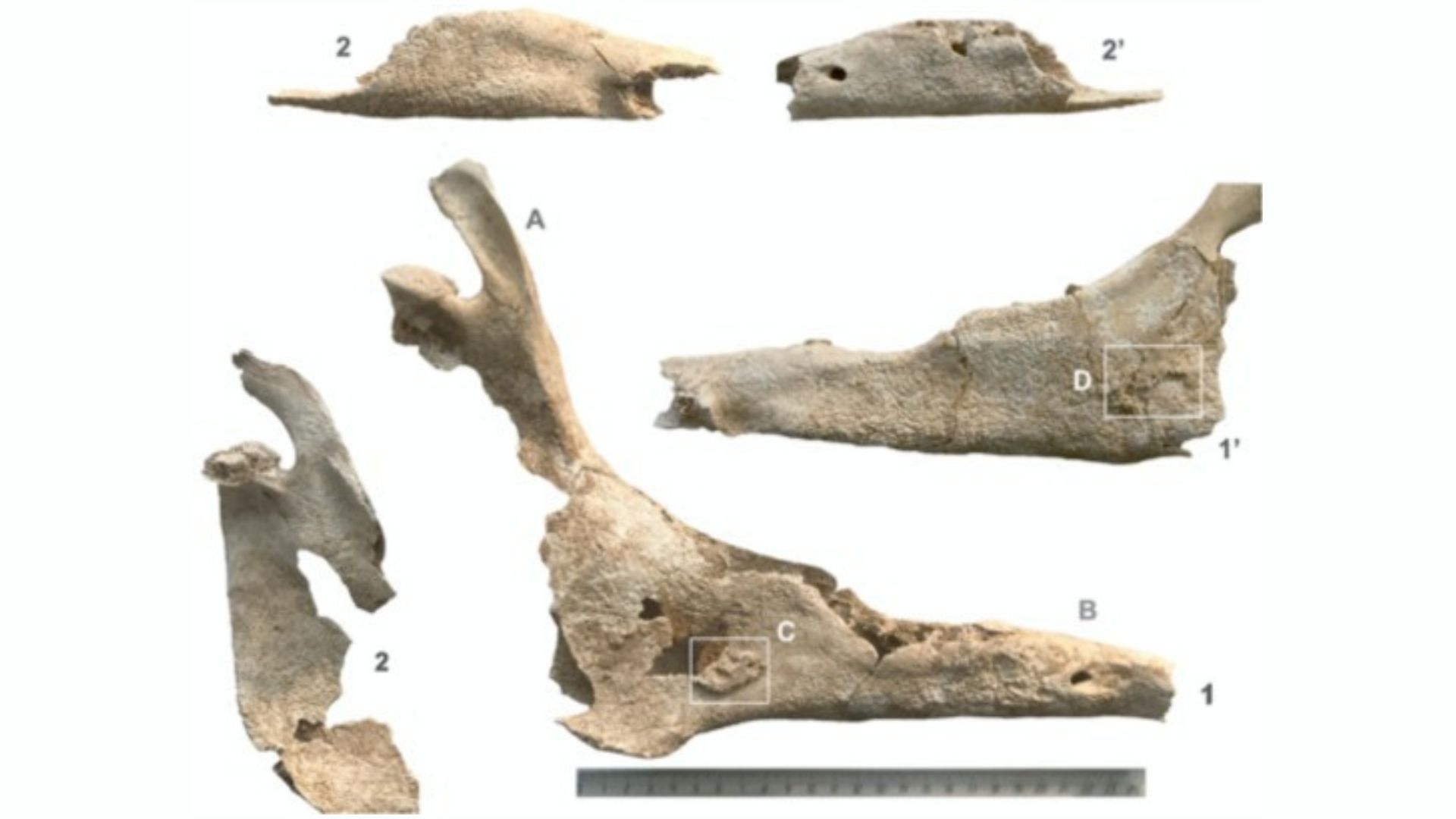

What the team saw in Yuka's muscle RNA reflects the potential horror of its last moments. Mármol Sánchez explained that they uncovered "molecular evidence of metabolic cell stress in Yuka's muscle," which corresponds with what a separate scientific team described in 2021. In that study, the researchers noted many claw marks that may have been made by cave lions (Panthera spelaea), as well as bite marks from smaller predators on the mammoth's body and tail. But whether Yuka was hunted and killed by large predators or simply scavenged after death is unknown. The researchers do not know what caused the cell stress observed in the RNA.

Federico Sánchez Quinto, a paleogenomicist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico's (UNAM) International Laboratory for Human Genome Research who was not involved in the research, considers this "a breakthrough publication in the field of paleogenomics." He described the study as "fascinating since it accomplishes something that had been previously unimaginable, as RNA is extremely unstable even in favorable conditions." Moreover, "this study obtains RNA from an older sample [than other recent RNA work], in larger amounts and with more certainty," he told Live Science in an email.

The findings have revealed that it's possible to extract RNA from extremely old specimens and showcases a new area of potential study for other researchers, the team said. In addition, the team has included a roadmap to help others successfully obtain ancient RNA.

"Being able to recover RNA from ancient samples, in addition to DNA, is like opening a new window into the biology of extinct animals," study co-author Love Dalén, professor of evolutionary genetics at the Centre for Palaeogenetics at Stockholm University, told Live Science. "It's yet another powerful tool that lets us see which genes were active in different cell types, which ultimately can help us better understand which genes made a mammoth a mammoth!”

Jeanne Timmons rediscovered her passion for paleontology later in life and eagerly started writing about it. Her work can be found in Gizmodo, Ars Technica, The New York Times and Scientific American.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus