Tapping Electrical Signals: Turning Thought Into Action

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This ScienceLives article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Like most things, mind reading comes down to the quality of your equipment.

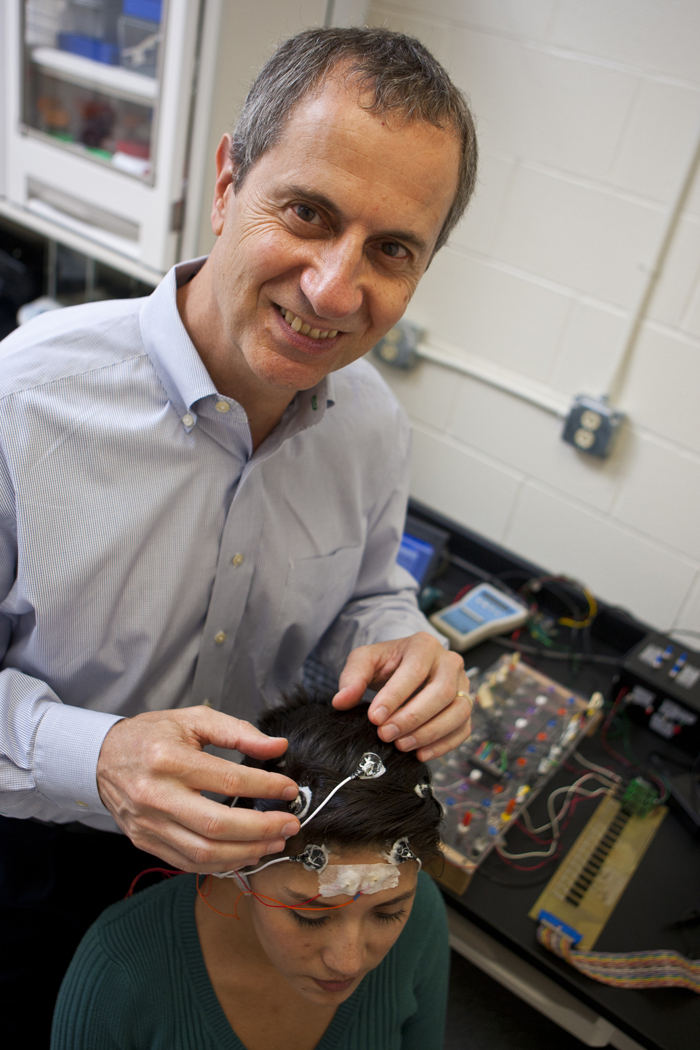

To turn thought into action, sensors must read the brain's noisy electrical signals, and then feed them to a computer, which decodes the signals and turns them into commands. While researchers have made many helpful mind-controlled machines, most sensors in use today are imprecise.

Walt Besio, a biomedical engineer, has developed a more sensitive electrode that can conduct electricity into and out of specific brain areas. He has already used it to pinpoint areas to treat epilepsy, a brain disorder associated with abnormal electrical activity.

Now, with support from the National Science Foundation's Innovation Corps and Small Business Innovation Research programs, Besio aims to make the electrodes commercially available.

For Besio, the motivation is personal as well as professional. He pursued neural engineering when his brother was paralyzed in an accident, hoping to help develop a technology that would enable him to move again.

Name: Walt Besio Age: It may be spring, but I'm no spring chicken. Institution: The University of Rhode Island Hometown: Kingston, R.I. Field of study: Neural engineering

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Why did you choose your field of research?

I got into this field because my brother was in an auto accident and was paralyzed from the neck down.

I wanted to do things to help him and people like him.

When I finished my bachelor's degree, I looked for companies that were working to reconnect spinal cords. There were none at the time, so I went on to grad school at the University of Miami where I did research to help cure paralysis. I've stayed with it ever since.

What was the best professional advice you ever received?

My family used to tease me that I was going to be a lifetime student because they didn't think I'd ever finish going to school. I went to school at night while I was working. It took many years.

The best professional advice came from my uncle. He said to talk with confidence. Whether you think you can do it or not, you have to convince people you can.

What are you most proud of?

My best project is seven-and-a-half years old. She consumes a lot of my time. She's an adaptive learning model. (That's my daughter.)

What was your biggest laboratory disaster, and how did you deal with it?

When I first got my faculty position, I was switching from studying the heart with my sensors to trying to study the brain. I spent nearly a year thinking I was getting brain signals. Then I realized it was just noise that looked like signals. Well, that didn't take a full year, but it did take a year to learn how to get the signals properly. That was just the worst.

What is the biggest challenge you are facing right now?

I hate to say it, but it's funding. In my position, I train students in higher education. Those students can be undergrads, grad or post docs. It costs a lot to do that.

What would surprise people most about your work?

That we can use our tripolar concentric ring electrodes to control seizures. We're able to do so non-invasively, on the scalp's surface. We've done it without using any drugs, and the seizures stopped for much longer than we expected after the stimulation.

Who is your biggest hero and why?

Lots of people have helped me along the way.

Two really come to mind. One is my uncle who gave me the advice about being confident in your abilities.

The other was my brother who was paralyzed. He made me realize how much to be thankful for. He was paralyzed for 25 years before he died. He was told he'd never be able to control anything again, that he'd always be paralyzed. But eventually we got his biceps and triceps working.

Also, my mother, who died when I was six months old. She gave up her life for me to be on this planet. She makes me appreciate being here.

What advice would you give to an aspiring engineer or scientist?

Don't give up. If you believe in something, keep trying.

Why should my [mom, kid sister, grandpa] be excited about your research?

The best is yet to come. The research that we're doing I believe — and many of my colleagues believe — will help a lot people and improve the quality of life for many people who are challenged right now.

Editor's Note: The researchers depicted in ScienceLives articles have been supported by the National Science Foundation, the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the ScienceLives archive.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus