'Hidden Dragon' Beast Gave Rise to Fearsome Flying Reptiles

A Chinese fossil is the earliest and most primitive pterodactyloid, part of a group of flying reptiles that ruled the skies some 163 million years ago, scientists report.

Winged creatures called pterosaurs evolved from a primitive form that lived about 228 million years ago into the largest flying creatures that ever existed. The new specimen helps fill in an important gap in that evolution, researchers say.

"This guy is the very first pterodactyloid — he has the last features that changed before the group radiated and took over the world," said paleontologist Brian Andres of the University of South Florida, a co-author of the study detailed today (April 24) in the journal Current Biology. [Photos of Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs]

(Researchers avoid calling pterodactyloids "pterodactyls," because the term is sometimes used to mean all pterosaurs and sometimes to mean just pterodactyloids, which include members of one of two suborders of pterosaurs.)

The finding extends the fossil record of pterodactyloids by at least 5 million years, to the Middle-Upper Jurassic boundary 163million years ago, Andres told Live Science.

Pterodactyloids are not ancestors of modern birds, which evolved from feathered dinosaurs.

Hidden dragon

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists named the new species Kryptodrakon progenitor, meaning "ancestral hidden serpent," because it was found in the area where the movie "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" was filmed.

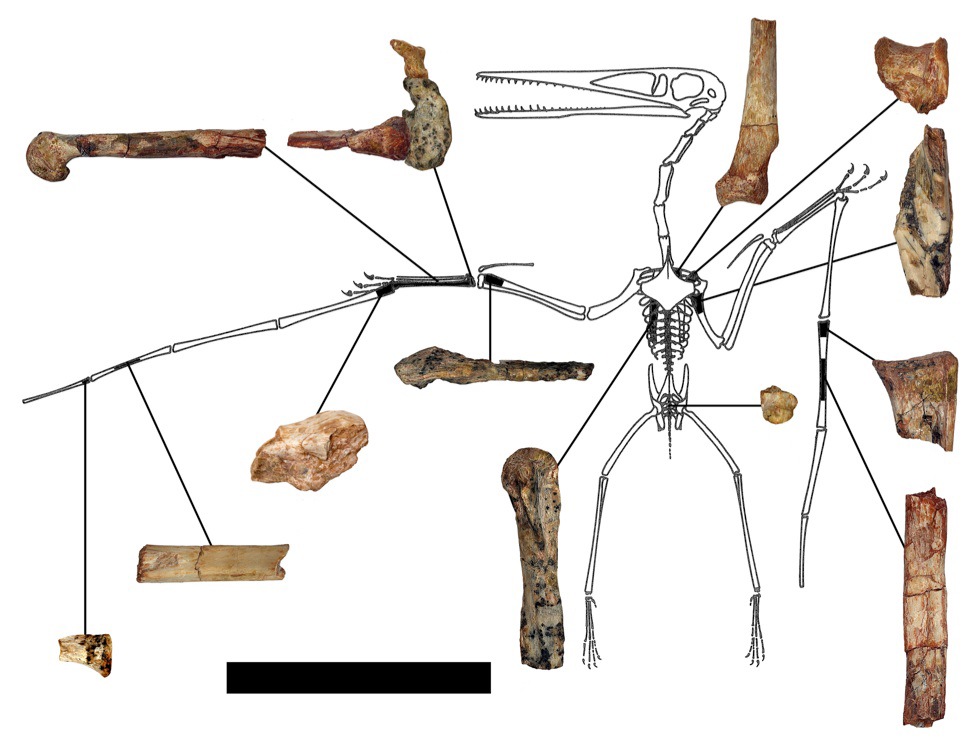

But this creature was no fearsome dragon. "He is a small guy, and [the fossil is] very fragmentary," Andres said.

The researchers analyzed the fossil fragments and found that Kryptodrakon had a wingspan of about 4.5 feet (1.4 meters), a far cry from the creature's enormous descendants, whose wingspans stretched up to 30 feet (9 m) — as large as a small airplane.

The researchers knew the creature was a pterodactyloid because of a signature bone in its palm used for walking and flying. In early pterosaurs, the bone is very short, attaches to the pinkie and doesn't vary much among individuals. But the corresponding bone in pterodactyloids is much longer, attaches to the ring finger and varies significantly.

Finger bones helped determine wing shape, and the change in this bone may have made pterodactyloids' wings better adapted to their environment, leading to their dominance of the skies, Andres said.

The team didn't find any skull pieces or teeth, so the researchers can't determine the creature's diet. However, relatives of Kryptodrakon have been known to eat insects, fish and even top predators, suggesting the animal was probably a carnivore.

Land fliers

Andres' colleagues discovered the fossil in a mudstone of the Shishugou Formation in northwest China on an expedition in 2001. The harsh, dry environment there is "as far as you can get from the ocean anywhere in the world," Andres said.

In general, paleontologists know a fossilized animal didn't necessarily live in the same environment where it was preserved. However, Andres and his team performed a sophisticated analysis of the fossil fragments that suggests Kryptodrakon did indeed live in a terrestrial environment.

By contrast, early pterosaurs are thought to have lived mostly in marine environments, though the animals returned to land a few times over the course of their evolution, the researchers said.

Andres said he wishes his team had found more fragments of Kryptodrakon. "We got there one year too late. Every year, more and more fossils erode out of the rock," he said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.