Chernobyl's nuclear fuel is 'smoldering' again and could explode

Tons of nuclear fuel in the wrecked plant's basement has started to react again, and it's showing no signs of stopping.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Nuclear reactions are smoldering again in an inaccessible basement of the wrecked Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine, according to news reports.

Researchers monitoring the plant — which infamously exploded in a deadly 1986 meltdown — have detected a steady spike in the number of neutrons in an underground room called 305/2. The room is full of heavy rubble, concealing a radioactive mush of uranium, zirconium, graphite and sand that oozed into the plant's basement like lava, before hardening into formations called fuel-containing materials (FCMs).

Rising neutron levels indicate that these FCMs are undergoing new fission reactions, as neutrons strike and split the nuclei of uranium atoms, creating energy.

Related: 5 Weird things you didn't know about Chernobyl

For now, this radioactive waste is smoldering "like the embers in a barbecue pit," Neil Hyatt, a nuclear materials chemist at the University of Sheffield in the U.K., told Science magazine. However, it's possible that those embers could fully ignite if left undisturbed for too long, resulting in another explosion.

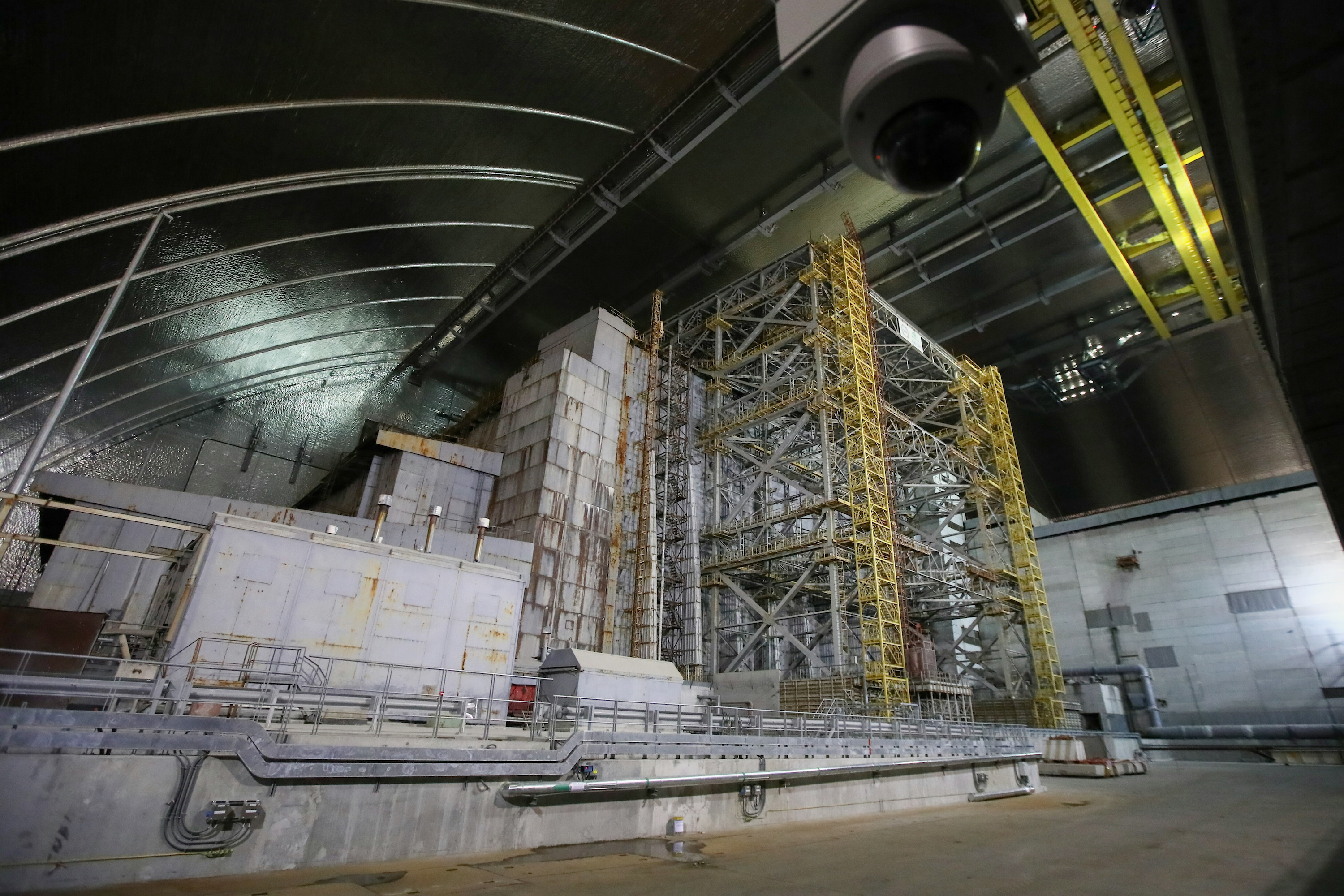

This potential explosion wouldn't be anywhere near as devastating as the one that shattered the plant in 1986, which resulted in thousands of deaths and spewed a radioactive cloud over Europe, Maxim Saveliev, a senior researcher with the Institute for Safety Problems of Nuclear Power Plants (ISPNPP) in Kyiv, Ukraine, told Science. If the nuclear material ignites again, the blast will be largely contained within the steel and concrete cage known as the Shelter, which officials built around the plant's ruined Unit Four reactor one year after the accident.

Still, even a contained explosion would make the long-term mission of removing the plant's FCMs much harder, Saveliev said. The Shelter is old and could easily crumble from the force of an explosion, filling the area with heavy debris and radioactive dust. (The Shelter itself is contained in a larger steel structure called the New Safe Confinement, which was completed in 2018.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Neutron levels have been steadily rising in room 305/2 for four years, Saveliev said, and could continue rising for several more years without incident. It's possible these nuclear nuggets will fizzle out on their own in that time. But if neutron levels keep rising, scientists will have to intervene.

That is more easily said than done, of course; plant managers have yet to figure out how to access the tons of radioactive material buried below the room's thick layers of concrete debris. Radiation levels are too high for humans to endure, but radiation-resistant robots might be able to drill through the rubble and install neutron-absorbing control rods into the room, according to the ISPNPP.

Ukraine hopes to present a detailed plan for the removal of Chernobyl's still-smoldering FCMs by September, Science reported.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus