Twice as Much Methane Escaping Arctic Seafloor

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

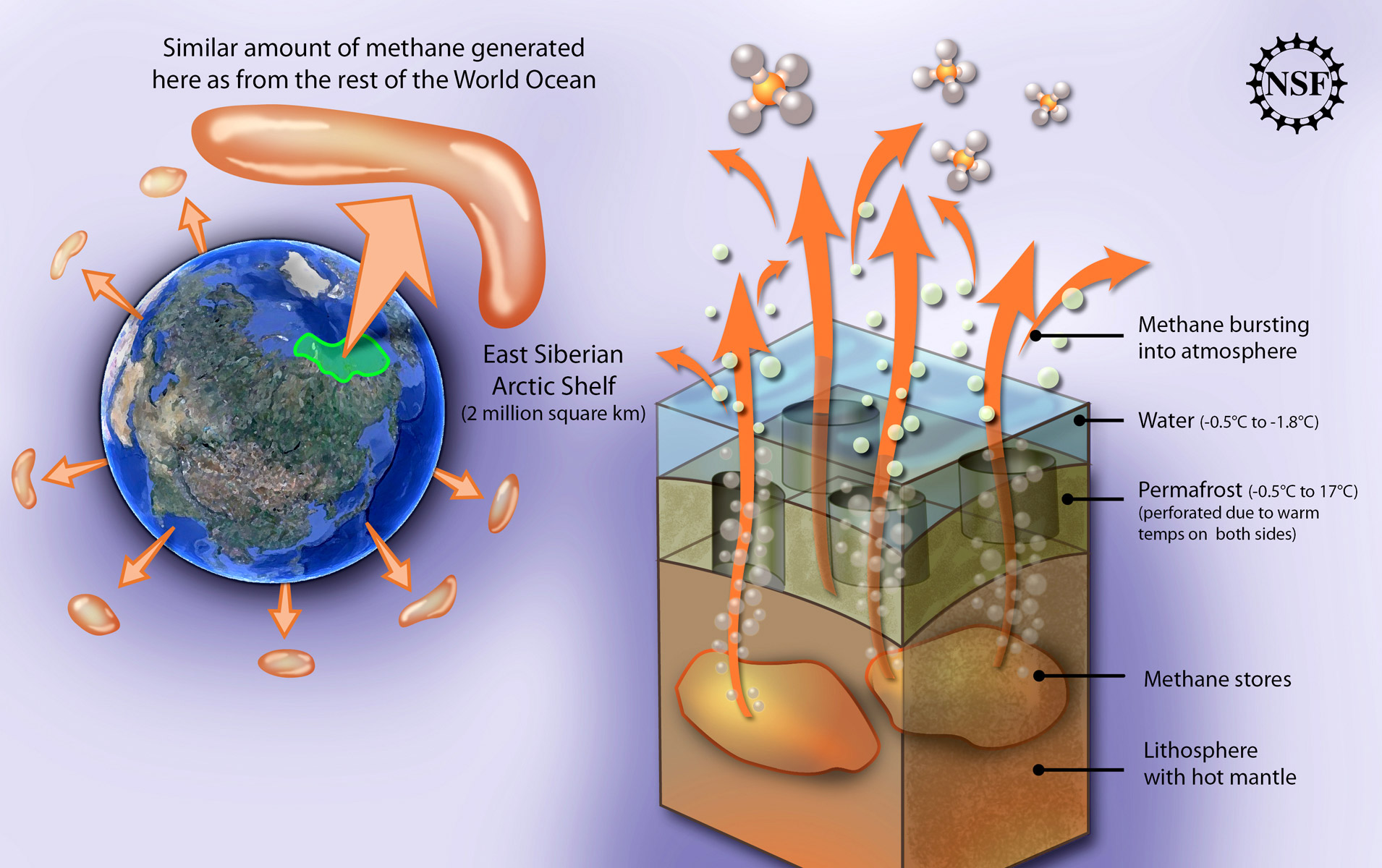

The Arctic methane time bomb is bigger than scientists once thought and primed to blow, according to a study published today (Nov. 24) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

About 17 teragrams of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, escapes each year from a broad, shallow underwater platform called the East Siberian Arctic Shelf, said Natalia Shakova, lead study author and a biogeochemist at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. A teragram is equal to about 1.1 million tons; the world emits about 500 million tons of methane every year from manmade and natural sources. The new measurement more than doubles the team's earlier estimate of Siberian methane release, published in 2010 in the journal Science.

"We believe that release of methane from the Arctic, in particular, from the East Siberian Arctic Shelf, could impact the entire globe, not just the Arctic alone," Shakova told LiveScience. "The picture that we are trying to understand is what is the actual contribution of the [shelf] to the global methane budget and how it will change over time."

Waiting to escape

Arctic permafrost is an area of intense research focus because of its climate threat. The frozen ground holds enormous stores of methane because the ice traps methane rising from inside the Earth, as well as gas made by microbes living in the soil. Scientists worry that the warming Arctic could lead to rapidly melting permafrost, releasing all that stored methane and creating a global warming feedback loop as the methane in the atmosphere traps heat and melts even more permafrost.

Researchers are trying to gauge this risk by accurately measuring stores of methane in permafrost on land and in the ocean, and predicting how fast it will thaw as the planet warms. Though methane gas quickly decays once it escapes into the atmosphere, lasting only about 10 years, it is 30 times more efficient than carbon dioxide at trapping heat (the greenhouse effect).

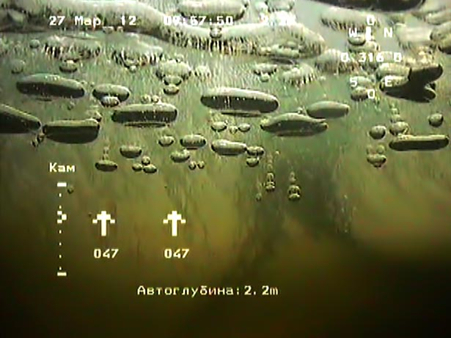

Shakova and colleague Igor Semiletov of the Russian Academy of Sciences first discovered methane bubbling up from the shallow seafloor a decade ago in Russia's Laptev Sea. Methane is trapped there in ground frozen during past ice ages, when sea level was much lower.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shallow waters

In their latest study, Shakova and her colleagues reported thousands of measurements of methane bubbles taken in summer and winter, between 2003 and 2012.

But the team also sampled seawater temperature and drilled into the ocean bottom, to see if the sediments are still frozen. Most of the survey was in water less than 100 feet (30 meters deep).

The shallow water is one reason so much methane escapes the Siberian shelf — in the deeper ocean, as methane-eating microbes digest the gas before it reaches the surface, Shakova said. But in the Laptev Sea, "it takes the bubbles only seconds, or at least a couple of minutes, to escape from the water column," Shakova said.

Arctic storms that churn the sea also speed up the release of methane from ocean water, like stirring a soft-drink releases gas bubbles, Shakova said. During the surveys, the amount of methane in the ocean and atmosphere dropped after two big Arctic storms passed through in 2009 and 2010, the researchers reported.

The temperature measurements revealed the water just above the ocean bottom warms by more than 12 degrees Fahrenheit (7 degrees Celsius) in some spots during the summer, the researchers found. And the drill core revealed that the surface sediment layers were unfrozen at the drill site, near the Lena River delta.

"We have now proved that the current state of subsea permafrost is incomparably closer to the thaw point than that of terrestrial permafrost," Shakova said.

Shakova and her colleagues attribute the warming of the permafrost to long-term changes initiated when sea levels rose starting at the end of the last glacial period. The seawater is several degrees warmer than the frozen ground, and is slowly melting the ice over thousands of years, they think.

Massive burst

But other researchers think the permafrost warming started only recently. "This is the first time in 12,000 years the Arctic Ocean has warmed up 7 degrees in the summer, and that's entirely new because the sea ice hasn't been there to hold the temperatures down," said Peter Wadhams, head of the Polar Ocean Physics Group at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., who was not involved in the study. The summer ice melt season has lasted longer since 2005, giving the sun more time to warm the ocean. [10 Things You Need to Know About Arctic Sea Ice]

"If we do have a methane burst it's going to be catastrophic," Wadhams said. Earlier this year, Wadhams and colleagues in Britain calculated that a mega-methane release from the Siberian shelf could push global temperatures up by 1 degree Fahrenheit (0.6 degrees Celsius). The suggestion, published in the journal Nature, was widely debated by climate researchers. Climate change experts and international negotiators have said that keeping the rise in Earth's average temperature below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) is necessary to avoid catastrophic climate change.

Shakova said much more research is needed to understand the factors that control how much methane is released from the entire East Siberian Arctic Shelf, which covers 772,000 square miles (2 million square kilometers), or nearly one-fifth the size of the United States.

"Ten years ago we started from zero knowledge in this area," Shakova said. "This is the largest shelf in the world's oceans. That's why it's very challenging to understand the natural processes behind the methane emissions in this area."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus