Microbes possibly feeding on the remains of an ancient forest may be generating billions of tons of methane deep beneath Antarctic ice, a new study suggests.

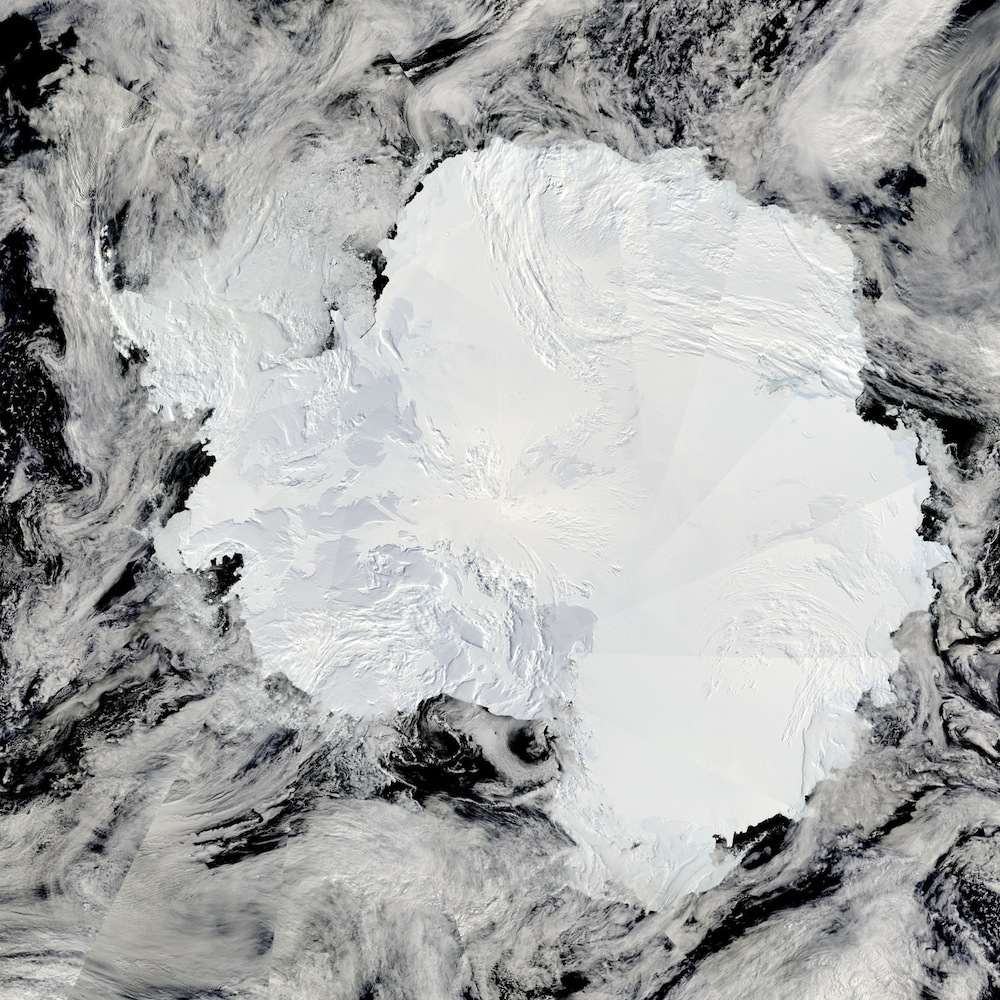

The amount of this greenhouse gas — which would exist in the form of a frozen latticelike substance called methane hydrate — lurking beneath the ice sheet rivals that stored in the world's oceans, the researchers said.

If the ice sheet collapses, the greenhouse gas could be released into the atmosphere and dramatically worsen global warming, researchers warn in a study published in the Aug. 30 issue of the journal Nature.

"There could be tons of methane hydrate beneath the Antarctic ice sheet," said study researcher Jemma Wadham of the University of Bristol’s School of Geographical Sciences. "If you start to thin that ice cover, that hydrate starts to become unstable and turns into gas, and that gas can go into the atmosphere."[Earth in the Balance: 7 Crucial Tipping Points]

Microbes produce methane

Microbes that thrive in extreme environments often create methane as a byproduct of their metabolism; the breakdown of organic carbon under no-oxygen conditions creates methane.

"It's a way of microbes getting energy under really, really oxygen-deprived conditions," Wadham told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

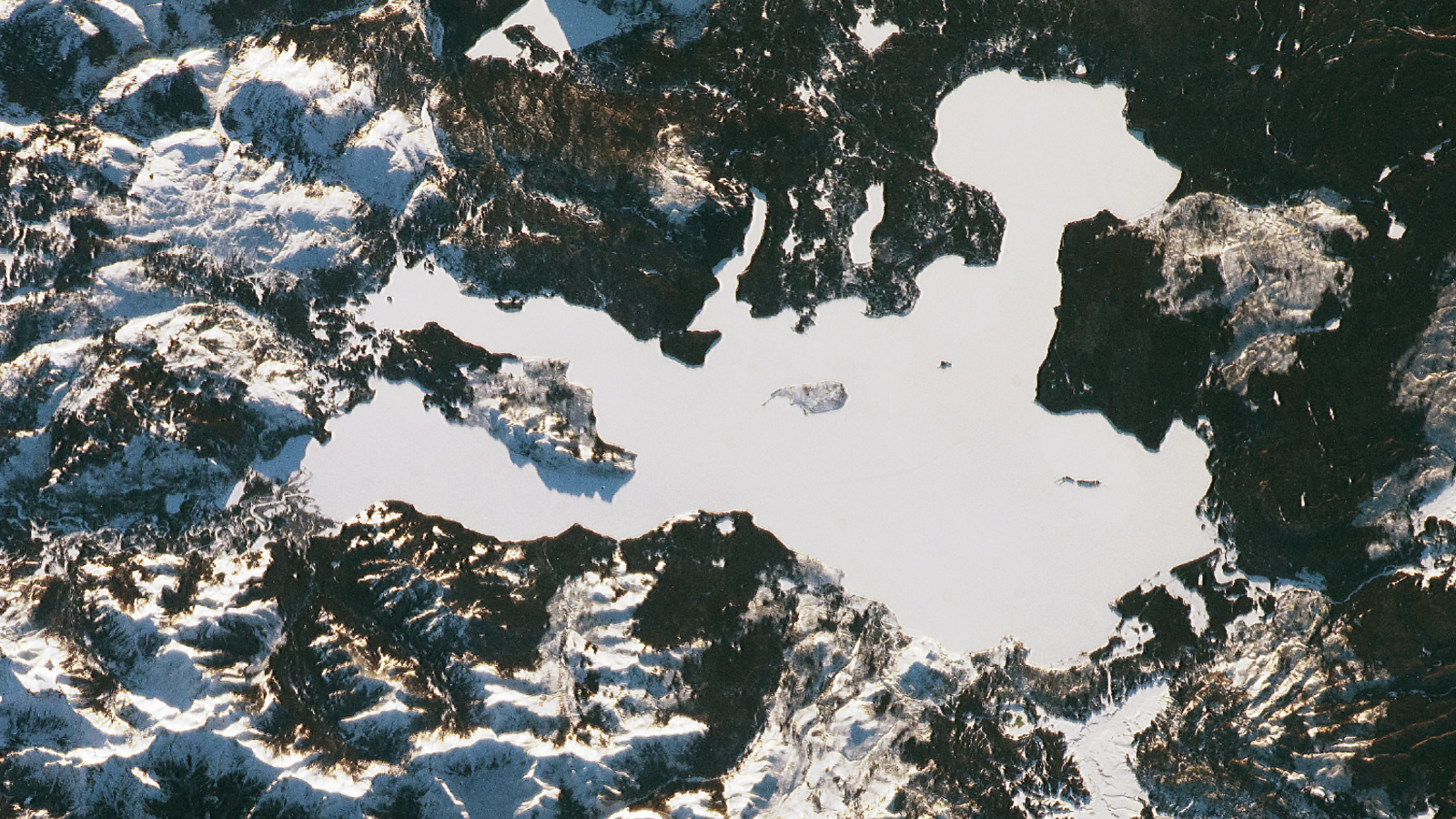

The team suspected that icy, silt-laden sediments trapped beneath the continental glacier could house such extremophiles. That’s because the sediments, possible relics of an ancient Antarctic forest and ocean, could provide a carbon-rich food source for methane producers. But drilling up to 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) through the ice to find out was extremely expensive and difficult.

Instead, Wadham and her colleagues sawed chunks of sediment from the fringes of an Antarctic glacier, where the ice was much thinner. They melted the ice and identified the methane-producing microbes living in the sediment.

They also placed the slurry in a cold, dark, oxygen-free environment for two years, and measured how much methane the microbes produced at several points in time.

Combining that information with models of Antarctic conditions and geology, the researchers estimated how much of the greenhouse gas could form over millions of years under Antarctica.

Mighty methane

Hundreds of billions of tons of carbon may lurk in methane reservoirs below the continent, the study found. That dwarfs the 600 million tons of carbon released through natural methane emissions like wetlands, livestock, burning of biomass and agriculture every year, she said.

Methane is a potent global warming gas, capable of trapping 20 times more heat than carbon dioxide, though it lingers in the atmosphere for much shorter periods of time.

The low temperature and high pressure from the ice sheet probably keeps the gas in a stable form called methane hydrate, or a methane molecule locked inside a cage of water molecules, said researcher Carolyn Ruppel of the U.S. Geological Survey, who was not involved in the study.

But if the ice sheets crack and disappear, which may happen due to climate change, the methane could slip free from that watery cage and enter the atmosphere rapidly, she said.

“That methane could substantially increase the concentration in the atmosphere, which would give you a global greenhouse gas warming event,” she said.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.