Weird Forests Once Sprouted in Antarctica

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

DENVER — Strange forests with some features of today's tropical trees once grew in Antarctica, new research finds.

Some 250 million years ago, during the late Permian and early Triassic, the world was a greenhouse, much hotter than it is today. Forests carpeted a non-icy Antarctic. But Antarctica was still at a high latitude, meaning that just as today, the land is bathed in round-the-clock darkness during winter and 24/7 light in the summer.

The question, said Patricia Ryberg, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute, is how plants coped with photosynthesizing constantly for part of the year and then not at all when the winter sun set.

"The trees are the best way to figure this out, because trees record physiological responses" in their rings, Ryberg told LiveScience.

A forest mystery

Fossilized wood and leaf impressions record a history of the Antarctic forests. The leaf impressions appear to show mats of leaves, as if the trees had all shed at once — a sign of a deciduous forest.

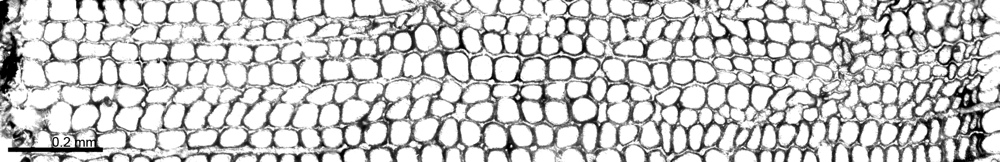

To confirm this, Ryberg and her colleagues gathered samples of fossil wood and examined the tree rings. Wood cells in the rings reveal how the trees grew: Early wood is produced when the tree is growing upward and outward. Late wood is produced when the tree is preparing to go dormant. At that point, the tree stops growing and starts storing carbon in its cells. Late wood is denser than early wood, and has thicker cell walls.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Deciduous and evergreen trees have different patterns of late and early wood. Ryberg and her colleagues examined the Antarctic fossils and found that they looked evergreen. [Image Gallery: Life at the South Pole]

"Now we have leaves that suggest a deciduous habit and fossil wood that is suggesting an evergreen habit, so we have a bit of a contradiction going on," Ryberg said here Wednesday (Oct. 30) at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America.

Mixed results

Follow-up studies analyzing carbon molecules in the fossil wood also gives both deciduous and evergreen answers, Ryberg said. The implication is that ancient Antarctic forests may have been a mix of deciduous and evergreen.

"It's not one or the other," she said. "It's actually both."

Much of the ring structure looks tropical, Ryberg added. Tropical trees that are not exposed to seasons experience a sort of short-term dormancy that echoes what is seen in the Antarctic wood.

"But they weren't growing in the tropics, so obviously it's two different environmental characteristics," Ryberg said.

Ryberg is now investigating how much plant matter these strange Antarctic forests produced. It's not yet clear whether the forests grew more densely than those seen in modern forests.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow OurAmazingPlanet @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus