Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Earth got most of its water from asteroid impacts nearly 4.6 billion years ago, shortly after the solar system first took shape, a new study suggests.

Researchers studying a meteorite that fell to Earth in 2000 found evidence that the water in its parent asteroid disappeared soon after the space rock formed, when its insides were still warm. Asteroids that slammed into Earth several hundred million years after the solar system's birth were thus probably relatively dry, scientists said.

"So, our results suggest that the water [was] supplied to Earth in the period when planets formed rather than the period of late heavy bombardment from 4.1 billion years to 3.8 billion years ago," study lead author Yuki Kimura, of Tohoku University in Japan, told LiveScience via email. [Photos: Asteroids in Deep Space]

Kimura and his colleagues analyzed the Tagish Lake meteorite, which landed in Canada's Yukon Territory in January 2000. Scientists think this rock — a type of meteorite known as a carbonaceous chondrite — is a piece of an asteroid that originated in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter.

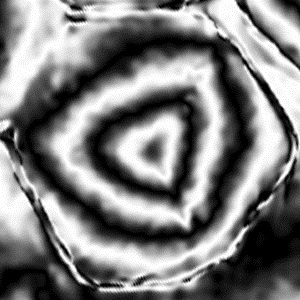

The scientists used a transmission electron microscrope to observe tiny particles of magnetite, which arranged themselves within the meteorite into three-dimensional "colloidal crystals."

These crystals can be formed during the sublimation of water — the transition of the material directly from ice to vapor — but not during freezing, Kimura said. This implies that the parent asteroid's bulk water disappeared in the early stages of the solar system's formation, before the space rock's innards had a chance to cool down, he added.

Other studies have also found support for very early water delivery to Earth. For example, a paper published this May in the journal Science found that water on the moon and Earth come from the same source.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The simplest explanation for this latter observation, researchers say, is that Earth was already wet by about 4.5 billion years ago, when a planet-size body is believed to have smashed into our planet, ejecting a huge amount of debris that eventually coalesced into the moon.

In addition to water, impacts likely delivered to the young Earth organic molecules — the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it. Indeed, the colloidal crystals in the Tagish Lake meteorite have an organic layer on their surface, Kimura said.

"Further analysis might give us some information about evolution of organic molecules in the early solar system," he said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus