Killer Waves: How Tsunamis Changed History

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In a jumbled layer of pebbles and shells called the "Dog's Breakfast deposit" lies evidence of a massive tsunami, one of two that transformed New Zealand's Maori people in the 15th century.

After the killer wave destroyed food resources and coastal settlements, sweeping societal changes emerged, including the building of fortified hill forts (pā) and a shift toward a warrior culture.

"This is called patch protection, wanting to guard what little resources you've got left. Ultimately it led to a far more war-like society," said James Goff, a tsunami geologist at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

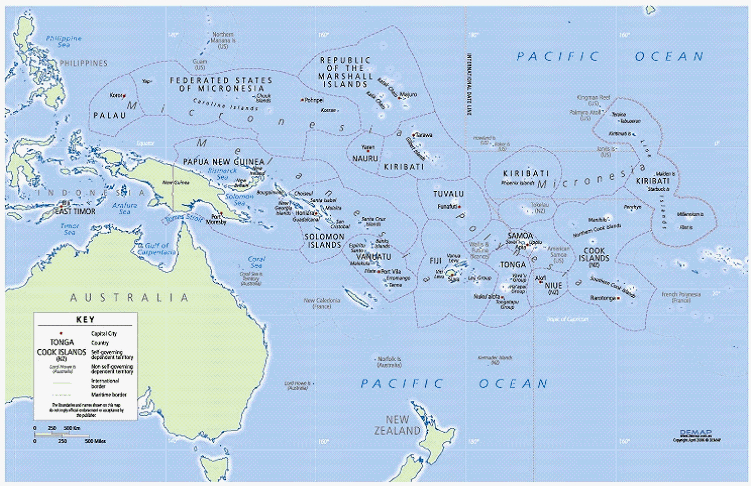

The Maori were victims of a one-two punch. An earthquake on the nearby Tonga-Kermadec fault triggered the first tsunami in the mid-15th century. It was soon followed by an enormous wave triggered by an exploding volcano called Kuwae, near Vanuatu. The volcano's 1453 eruption was 10 times bigger than Krakatoa and triggered the last phase of worldwide cooling called the Little Ice Age.

The tsunamis mark the divide between the Archaic and Classic periods in Maori history, Goff said. "The driver is this catastrophic event," he told OurAmazingPlanet.

Goff is one of many scientists searching for ancient tsunamis in the Pacific and elsewhere. The devastating 2004 Indonesia tsunami and earthquake, which killed 280,000 people, brought renewed focus on the hazards of these giant waves. Understanding future risk requires knowing where tsunamis struck in the past, and how often. As researchers uncover signs of prehistoric tsunamis, the scientists are beginning to link these ocean-wide events with societal shifts.

"Following 2004, there has been a lot of re-thinking and a greater appreciation for how such events would have impacted coastal settlements," said Patrick Daly, an archaeologist with the Earth Observatory of Singapore.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Vulnerable islands

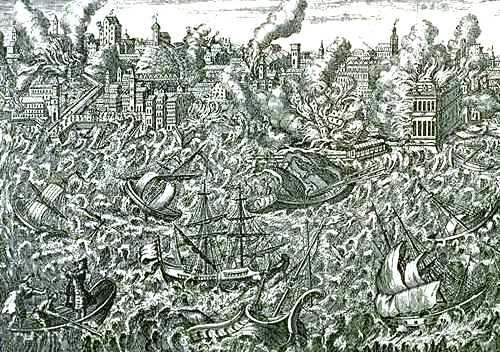

The West's written history and legends clearly illustrate the consequences of tremendous tsunamis in the Mediterranean. A great wave destroyed Minoan culture on the Greek island of Crete in 1600 B.C. The same tsunami may be responsible for the legend of Atlantis, the

verdant land drowned in the ocean. More recently, in 1755, an enormous tsunami destroyed Lisbon, Portugal, Europe's third-largest city at the time. The destruction influenced philosophers and writers from Kant to Voltaire, who references the event in his novel "Candide." [10 Tsunamis That Changed History]

But islands face a much greater threat from tsunamis than coastal communities. After the Lisbon tsunami, the king of Portugal immediately set out to rebuild the city, which was only possible thanks to the presence of untouched inland areas.

"An island becomes totally cut off from the outside world," said Uri ten Brink, a marine geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Woods Hole, Mass. "Islands are a lot more vulnerable to such disasters. It's the same kind of thing as during bad hurricanes. It takes a lot longer to recover."

Exposed on all sides, islands are simply more likely to be hit by tsunamis. People settle in shallow bays, which are protected from storms but actually magnify the height of incoming tsunami waves. Food in these societies comes from marine resources, which are destroyed by tsunamis, and croplands that become inundated with saltwater. Boats are smashed, halting trade and communication. Goff said women, children and the elderly are most likely to die, and in Polynesian culture, elders hold the knowledge needed to build boats, make tools and grow food.

The islands of the Pacific are particularly vulnerable. About 85 percent of the world's tsunamis strike in the Pacific Ocean, thanks to its perilous tectonics. Tsunamis are waves triggered when earthquakes, landslides or volcanic eruptions shove a section of water. Ringed by subduction zones, spots where one of Earth's plates slides beneath the other, the Pacific suffers the world's most powerful earthquakes, and it holds the highest concentration of active volcanoes.

But the kind of tsunami that can change history, one that sweeps across the entire ocean, is rare.

"There are many tsunamis where there's been no cultural response or no obvious one," Goff said. "The smaller events aren't going to be the game changers."

Polynesia and tsunamis

But Goff thinks he's found a "black swan" that hit 2,800 years ago, the result of an enormous earthquake on the Tonga-Kermadec subduction zone, where two of Earth's tectonic plates collide. The tsunami scoured beaches throughout the Southwest Pacific, leaving distinctive sediments for scientists to decode. Goff's findings are detailed in several studies, most recently in the February 2012 issue of the journal The Holocene.

The tsunami coincides with the mysterious long pause, when rapid Polynesian expansion inexplicably stopped for 2,000 years. Before the pause, settlers had swiftly crossed from New Guinea to Fiji, Tonga and Samoa over the course of about 500 years.

"It's one of those archaeological conundrums," Goff said. "Why? Well, if I just had my culture obliterated, it might take me a little time to recover. It's probably not the only explanation, but it very well could have been the root cause of why they stopped," he told OurAmazingPlanet.

Two tsunamis in the 15th century had a similarly chilling effect on Polynesian society. After leaving Samoa between AD 1025 and 1120, Polynesians spread across the Pacific Ocean, discovering nearly all of the 500 habitable islands there, according to a study published Feb. 1, 2011, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The Polynesian network covered an area the size of North America, all traversed by wooden canoes. [7 Most Dangerous Places on Earth]

Following the tsunamis, the culture contracted, with the rise of chiefdoms, insularity and warfare, Goff said. "There was a major breakdown at exactly that time," Goff said. "You have to live on what you have on your island, and that causes warfare and a fundamental shift in how they go about living."

Indian Ocean tsunami history

Paleotsunamis also froze trade in the Indian Ocean, according to recent studies by geologists and archaeologists.

Along the Sunda fault off the Indonesian island of Sumatra, which spawned the deadly 2004 tsunami, growth patterns in coral reefs record past earthquakes. Combined with sediment layers that point to past tsunamis and historic records of cultural shifts, the clues suggest a 14th century tsunami with an impact as great as the modern cataclysm.

After the 14th-century tsunami, Indian Ocean traders shifted to the sheltered northern and eastern coasts in the Straits of Malacca, and activity ceased in coastal settlements in the same area hit by the 2004 wave, said Daly of Singapore's Earth Observatory.

"We think that the 14th century tsunami disrupted one of the main trading routes connecting the Indian Ocean with China and Southeast Asia, a far more powerful impact on a global scale than what happened in 2004," Daly said.

After about a century, there was a gradual shift back, leading to the establishment of the flourishing Acehnese Sultanate from the 16th century, he said.

"It is interesting to think that later settlement only began after the memory of the previous event had faded," Daly told OurAmazingPlanet. "A huge, unexpected deluge of water that wiped out everything along the coast would have been really traumatic and incomprehensible to people in the past, and it is reasonable to suspect that the survivors would have been very apprehensive about moving back into such areas."

Repeating the past

Warnings would be passed down in oral or written stories and legends. The Maori offer detailed accounts of a series of great waves that hit the New Zealand coast. Along the Cascadia subduction zone, west of Washington State, tribal mythology documents a 1700 tsunami, with warnings to flee to high ground.

But because history-changing waves are rare, the warnings may be lost to time, or disregarded. In Japan, stone markers warned of the height of past tsunamis, and told residents to flee after an earthquake. Not all heeded the ancient admonitions when the 2011 Tohoku earthquake struck and sent a massive wave ashore.

By studying past tsunamis and their causes, researchers such as Goff and ten Brink of the USGS hope to reduce the destruction and loss of life from future waves. Right now, ten Brink is on Anegada Island in the Caribbean, investigating whether a tsunami there between 1450 and 1600 came from Lisbon or a local source. The project started as a hunt for evidence of a magnitude 9.0 earthquake, one similar in size to those in Japan and Sumatra. Goff is assembling a database of Pacific paleotsunamis, including the 1450 wave, which ran 100 feet (30 meters) inland along the New Zealand coast.

"The reason we're interested in looking at old tsunamis is we're worried about how often these things happen," Goff said.

The question is whether increased knowledge about the scope and frequency of tsunamis will change current and future decision-making. [Read: Tsunami Warnings: How to Prepare]

"The early evidence from the last few destructive tsunamis suggests that we don't necessarily learn lessons that well, and people in general seem to be willing to remain in highly vulnerable areas," Daly said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook or Google +. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus