Earth's Earliest Dinosaur Possibly Discovered

A wonky beast about the size of a Labrador retriever with a long neck and lengthy tail may be the world's earliest known dinosaur, say researchers who analyzed fossilized bones discovered in Tanzania in the 1930s.

Now named Nyasasaurus parringtoni, the dinosaur would've walked a different Earth from today. It lived between 240 million and 245 million years ago when the planet's continents were still stitched together to form the landmass, Pangaea. Tanzania would've been part of the southern end of Pangaea that also included Africa, South America, Antarctica and Australia.

It likely stood upright, measuring 7 to 10 feet (2 to 3 meters) in length, 3 feet (1 m) at the hip, and may have weighed between 45 and 135 pounds (20 to 60 kilograms).

"If the newly named Nyasasaurus parringtoni is not the earliest dinosaur, then it is the closest relative found so far," said lead researcher Sterling Nesbitt, a postdoctoral biology researcher at the University of Washington.

The findings, detailed online Dec. 5 in the journal Biology Letters, push the dinosaur lineage back 10 million to 15 million years than previously known, all the way into the Middle Triassic, which lasted from about 245 million to 228 million years ago. [See Photos of the Oldest Dinosaur Fossils]

Dating a dinosaur

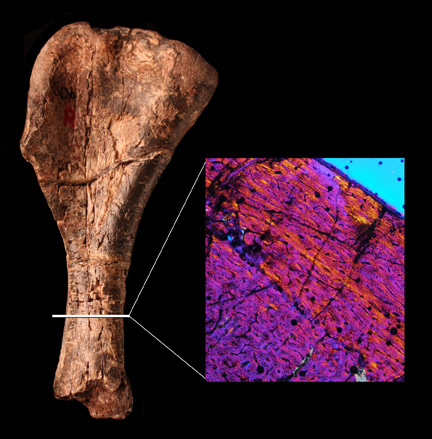

The study is based on seemingly few bones — a humerus or upper arm bone and six vertebrae — though Nesbitt pointed out much of what we know about dinosaurs comes from similar number of fossils. Only a rare few dinosaurs are excavated with near-complete skeletons, a la museum centerpieces.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For their study, the researchers had to determine whether the bones indeed belonged to a dinosaur and how long ago the beast would've lived.

They dated the fossils based on the layer of rock in which it was found and the ages for the layers above and below it (over time layers of sediment accumulate on top of remains, making a vertical slice somewhat of a timeline into the past).

They also looked at the ages of rock layers with similar animal remains found across the globe.

As for whether the beast is a dinosaur, several clues say it is. For instance, dinosaurs grew quickly, and a cross-section of the humerus suggests bone tissue was laid down in a haphazard way, a telltale sign of rapid growth.

"We can tell from the bone tissues that Nyasasaurus had a lot of bone cells and blood vessels," said co-author Sarah Werning of the University of California, Berkeley, who did the bone analysis. "In living animals, we only see this many bone cells and blood vessels in animals that grow quickly, like some mammals or birds," Werning said in a statement.

The upper arm bone also sported a distinctively enlarged crest that would've served as a place of attachment for arm muscles.

"It's kind of your shoulder muscle or the equivalent in a dinosaur," Nesbitt told LiveScience, adding that "early dinosaurs are the only group to have this feature."

Vertebrate paleontologist and geologist Hans-Dieter Sues, who was not involved in the study, agrees with the dating and dinosaur tag placed on the remains. "I first saw the bones in the 1970s when the late Alan Charig (one of the co-authors) showed them to me," Sues, of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., told LiveScience in an email. At that time none of his colleagues would accept that dinosaurs had appeared so early in geological history."

Sues added that additional, more complete remains are needed to confirm the relationships between Nyasasaurus and other dinosaurs. [6 Weird Species Discovered in Museums]

Answering a long-standing question

Paleontologists have for about 150 years suggested dinosaurs existed in the Middle Triassic, as the oldest dinosaur fossils fit into the Late Triassic period. However, that evidence has been fraught with uncertainty, with conclusions based on only dinosaurlike footprints or very fragmentary fossils. Footprints can be tricky to interpret, in this case, because other animals roaming Earth at the time would've made similar pedal prints.

"Previous to this find, all the oldest dinosaurs were all equally old from the same place in Argentina, and those sediments are about 230 million years [old]. So this pushes the dinosaur lineage or the closest relative to dinosaurs all the way back to the Middle Triassic," Nesbitt said during a telephone interview. "This is our best evidence of a Middle Triassic dinosaur."

In addition to pushing back the timeline for dinosaurs, Nesbitt says the study also reveals how dinosaurs emerged on Earth. Rather than waking up on the planet as the dominant beasts during their heydays in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, dinosaurs gradually ramped up to their reign.

"They were a unique group, but they didn't evolve and take over terrestrial ecosystems immediately," Nesbitt said. "Most of what we see in museums are from the Jurassic and Cretaceous when they did dominate — at their origins they were just a part of the radiation of Archosaurs," or the dominant land animals during the Triassic period that included dinosaurs, crocodiles and their relatives.

Nesbitt hopes the discovery will encourage other paleontologists digging in Middle Triassic rocks to keep a lookout for dinosaurs — fossils, that is.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.