Giant crack frees a massive iceberg in Antarctica

A giant iceberg, more than 20 times the size of Manhattan, just split off from Antarctica's Brunt Ice Shelf.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

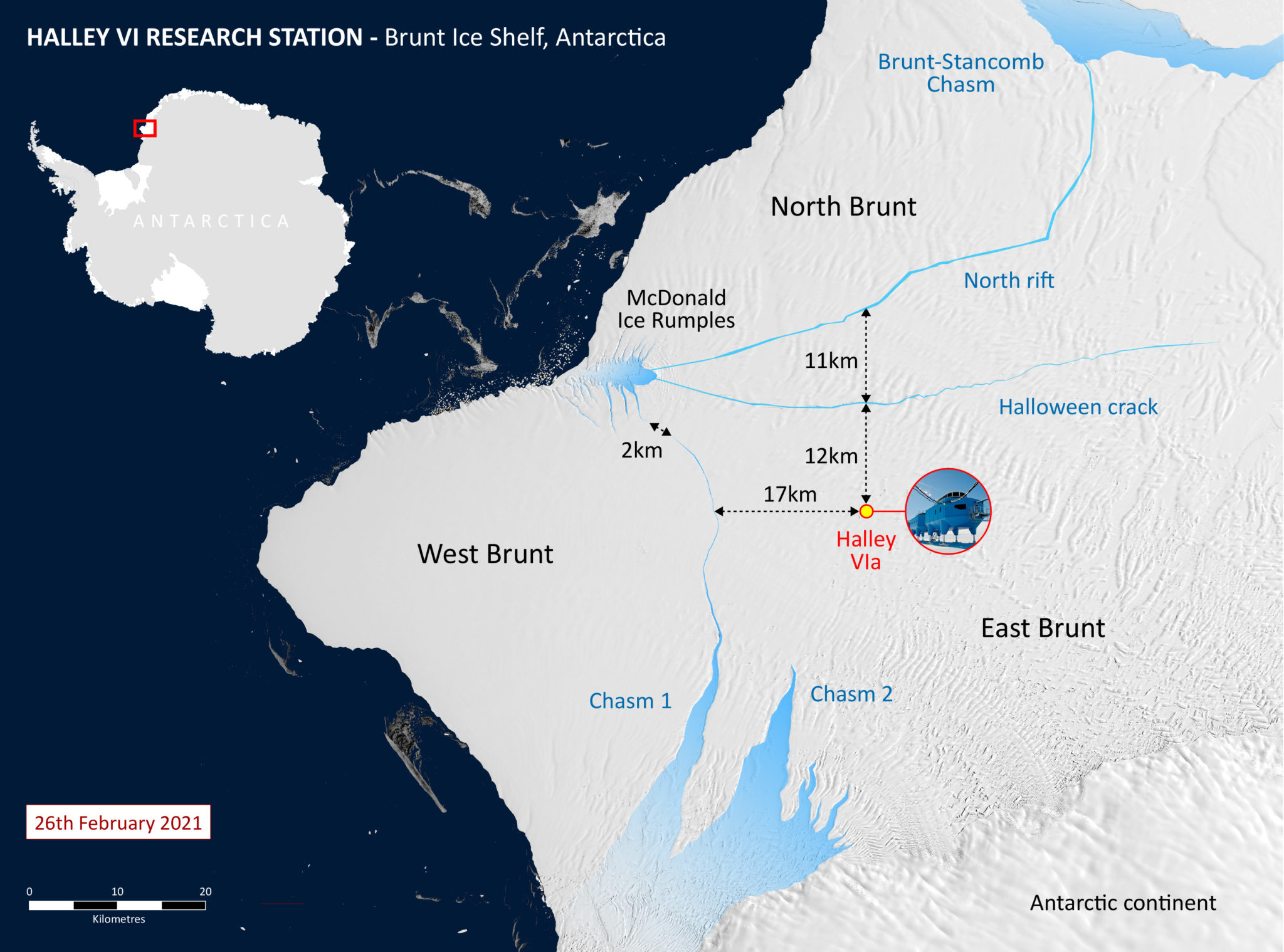

A giant iceberg, more than 20 times the size of Manhattan, just split off from Antarctica's Brunt Ice Shelf. This dramatic breakup comes after a major crack formed on the shelf in November 2020 and continued to grow until the 'berg finally broke off Friday morning (Feb. 26).

The so-called "North Rift" crack is the third major chasm to actively tear across the Brunt Ice Shelf in the last decade, and so scientists with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) were absolutely expecting the split.

"Our teams at BAS have been prepared for the calving of an iceberg from Brunt Ice Shelf for years," Dame Jane Francis, the director of the BAS, said in a statement. "Over [the] coming weeks or months, the iceberg may move away; or it could run aground and remain close to Brunt Ice Shelf." (Icebergs are pieces of ice that have broken off from glaciers or ice shelves and are now floating in open water, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration).

Related: Photos: diving beneath Antarctica's ross ice shelf

The North Rift crack grew toward the northeast at a rate of about 0.6 miles (1 km) per day in January; but on the morning of Feb. 26, the crack widened a couple hundred meters in just hours. This ice split happened due to a natural process, and there's no evidence that climate change played a role, according to the statement. The Brunt Ice Shelf, a 492-foot-thick (150 meters) slab of ice, flows west at 1.2 miles (2 km) per year and routinely calves icebergs.

This iceberg, however, happened to be very big, with an estimated size of about 490 square miles (1,270 square km).

"Although the breaking off of large parts of Antarctic ice shelves is an entirely normal part of how they work, large calving events such as the one detected at the Brunt Ice Shelf on Friday remain quite rare and exciting," Adrian Luckman, a professor at Swansea University in Wales who was tracking the shelf through satellite images in the last few weeks, told the BBC.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Brunt Ice Shelf is home to the BAS Halley VI research station, where scientists observe atmospheric and space weather; but the station will likely not be affected by this splitting, according to the statement.

Related: Photos: Behind the scenes of an Antarctic research base's relocation

In 2016, the BAS relocated the station 20 miles (32 km) inland to avoid the two other major cracks in the ice shelf known as "Chasm 1" and the "Halloween Crack," both of which haven't widened any further in the past 18 months, according to the statement.

The research station is now closed for winter, and the 12-person team left Antarctica earlier in February. Because of the unpredictability of iceberg calving, and the difficulty of evacuating during the dark and frigid winters, the research team has been working at the station only during the Antarctic summer over the past four years.

More than a dozen GPS monitors measure and relay information about ice deformation of the shelf back to the team in the U.K. every day. The researchers also use satellite images from the European Space Agency, NASA and the German satellite TerraSAR-X to monitor the ice.

"Our job now is to keep a close eye on the situation and assess any potential impact of the present calving on the remaining ice shelf," Simon Garrod, the BAS director of operations, said in the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus