Asteroid Crashes Likely Gave Earth Its Water

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

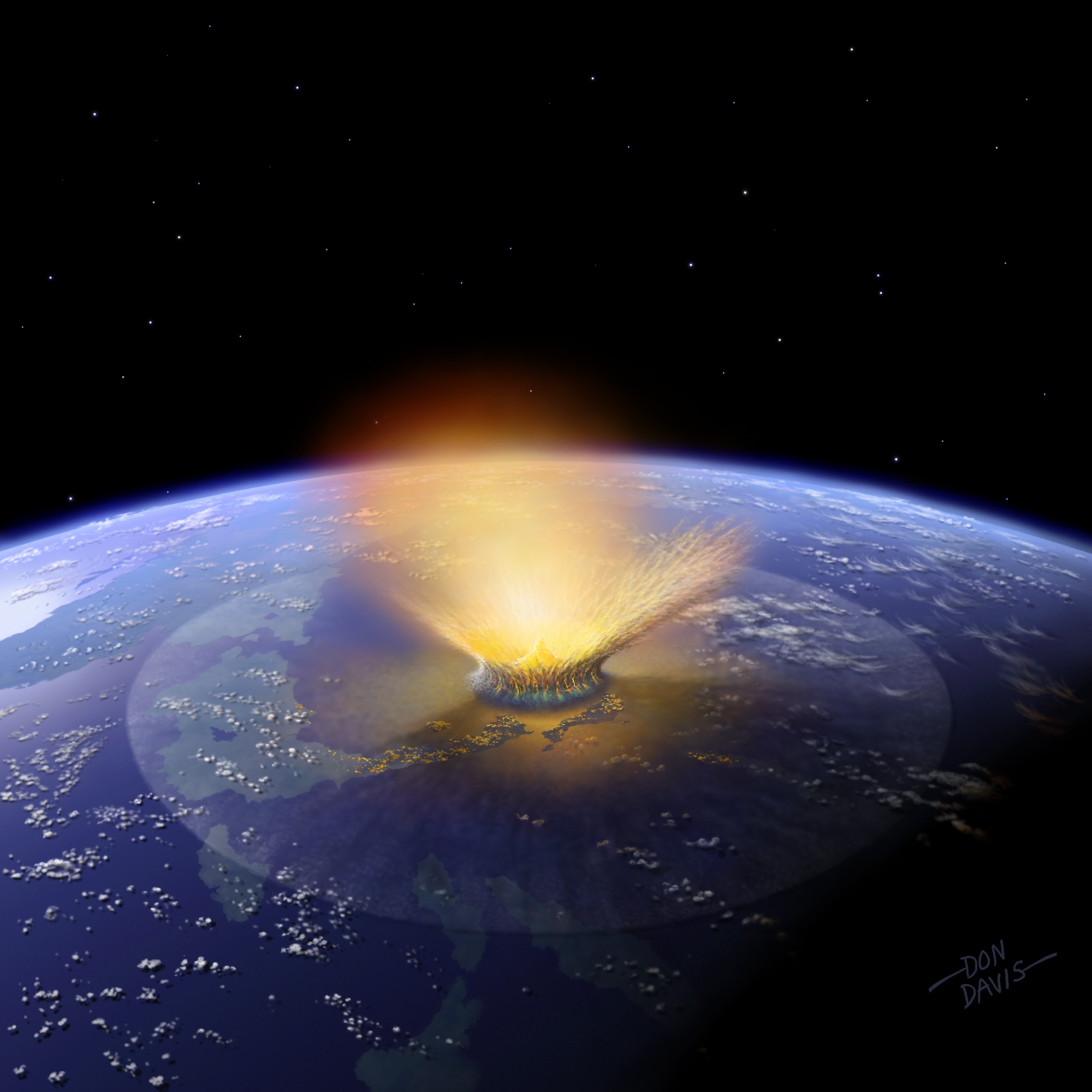

Asteroids from the inner solar system are the most likely source of the majority of Earth's water, a new study suggests.

The results contradict prevailing theories, which hold that most of our planet's water originated in the outer solar system and was delivered by comets or asteroids that coalesced beyond Jupiter's orbit, then migrated inward.

"Our results provide important new constraints for the origin of volatiles in the inner solar system, including the Earth," lead author Conel Alexander, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, said in a statement. "And they have important implications for the current models of the formation and orbital evolution of the planets and smaller objects in our solar system."

Alexander and his colleagues analyzed samples from 86 carbonaceous chondrites. These primitive meteorites are thought to be key sources of the early Earth's volatile elements, such as hydrogen and nitrogen.

The team measured the abundance of different hydrogen, nitrogen and carbon isotopes in the chondrite samples. Isotopes are versions of an element that have different numbers of neutrons in their atomic nuclei. For example, the isotope deuterium — also known as "heavy hydrogen" — contains one neutron, while "normal" hydrogen has none.

The amount of deuterium in celestial bodies' water ice sheds light on where the objects formed in the solar system's early days. In general, bodies that took shape farther from the sun have relatively higher concentrations of deuterium, researchers said.

The 86 chondrite samples' deuterium content — which the team gleaned from clays, the remnants of water ice — suggest the meteorites' parent bodies formed relatively close to the sun, perhaps in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Comets, by contrast, have much higher deuterium ratios. As a result, scientists think most of them were born in the solar system's frigid outer reaches.

The isotopic composition of the bulk Earth appears to be more consistent with chondrites than with comets, researchers said. There are many different types of chondrites, and no single group is a perfect match. So our planet probably accreted its water and other volatiles from a variety of chondrite parent asteroids, they added.

The study appears today (July 12) online in the journal Science.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus