Misbehaving Particles Poke Holes in Reigning Physics Theory

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

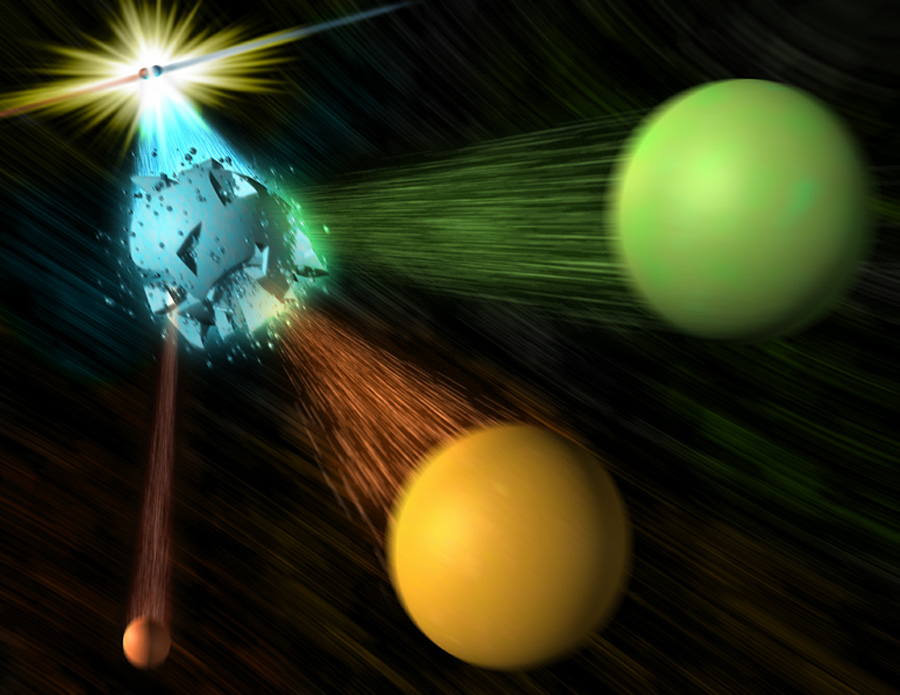

The reigning theory of particle physics may be flawed, according to new evidence that a subatomic particle decays in a certain way more often than it should, scientists announced.

This theory, called the Standard Model, is the best handbook scientists have to describe the tiny bits of matter that make up the universe. But many physicists suspect the Standard Model has some holes in it, and findings like this may point to where those holes are hiding.

Inside the BaBar experiment at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, Calif., researchers observe collisions between electrons and their antimatter partners, positrons (scientists think all matter particles have antimatter counterparts with equal mass but opposite charge). When these particles collide, they explode into energy that converts into new particles. These often include so-called B-bar mesons, which are made of both matter and antimatter, specifically a bottom quark and an antiquark. If that wasn't too much of a headache, this process has the impenetrable moniker "B to D-star-tau-nu."

The BaBar researchers were looking for a particular decay process where B-bar mesons decay into three other particles: a D meson (a quark and an antiquark, one of which is "charm" flavored), an antineutrino (the antimatter partner of the neutrino) and a tau lepton (a cousin of an electron). [Graphic: Nature's Tiniest Particles Explained]

What they found is that this process apparently happens more often than the Standard Model predicts it will.

"The excess over the Standard Model prediction is exciting," BaBar spokesperson Michael Roney of the University of Victoria in Canada said in a statement. "But before we can claim an actual discovery, other experiments have to replicate it and rule out the possibility this isn't just an unlikely statistical fluctuation."

While the BaBar findings are more sensitive than previous studies of these decays, they are not statistically significant enough to claim they present a clear break from the Standard Model.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To confirm the findings, more data will be needed from other experiments, such as the Belle project at the High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK) in Tsukuba, Japan, which also produces B mesons.

"If the excess decays shown are confirmed, it will be exciting to figure out what is causing it," said BaBar physics coordinator Abner Soffer of Tel Aviv University. "We hope our results will stimulate theoretical discussion about just what the data are telling us about new physics."

The BaBar experiment observed particle collisions between 1999 to 2008, but physicists are still analyzing the data. Researchers from the team presented their findings at the 10th annual Flavor Physics and Charge-Parity Violation Conference in Hefei, China, and detailed them in a paper submitted to the journal Physical Review Letters.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus