What We Learned About Our Human Ancestors in 2011

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Genetic hints of extinct human lineages — and the benefits we might have received from having sex with them — were among the discoveries this year regarding the evolution of our species.

Other key findings include evidence strengthening the case that fossils in South Africa might be those of the ancestor of the human lineage. Research also suggests humans crossed what is now the desolate Arabian Desert to expand out of Africa across the world.

Sex with extinct human lineages

Although we modern humans are the only surviving members of our lineage, other kinds of humans once roamed the Earth, including familiar Neanderthals and the newfound Denisovans, who lived in what is now Siberia. Although some researchers once scoffed at the notion that our ancestors interbred with such extinct lineages, genetic analysis suggests that Neanderthal DNA makes up 1 percent to 4 percent of modern Eurasian genomes, while Denisovan DNA makes up 4 percent to 6 percent of modern Melanesian genomes.

"Everywhere you look now, we find a little bit of interbreeding," said population geneticist Michael Hammer at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Our species might have also hybridized with a now-extinct lineage of humanity before leaving Africa, according to findings this year from Hammer and his colleagues. Approximately 2 percent of contemporary African DNA might have come from a lineage that first diverged from the ancestors of modern humans about 700,000 years ago. For context, the Neanderthal lineage diverged from ours within the past 500,000 years, while the first signs of anatomically modern human features emerged only about 200,000 years ago.

Hammer noted that he and his colleagues were very conservative with their analysis, only looking for lineages that diverged even more from modern humans than Neanderthals. "It's possible there may be others we can detect that are more closely related to modern humans," Hammer told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We've probably just scratched the surface of what we might find," Hammer added. "We only looked at a small number of regions of the genome. This coming year, you'll see a lot of progress made with full genome data. This year, we should be able to confirm what we found and go way beyond that."

Such canoodling had lasting effects on human evolution — sex with extinct human lineages might have endowed some of us with the robust immune systems we enjoy today. So-called HLA genes help our immune systems defend our bodies, and this year scientists discovered HLA variants that apparently originated in Denisovans and Neanderthals made their way into modern Eurasian and South Pacific groups, perhaps helping to protect our species as we expanded out of Africa.

"We will definitely learn quite a bit more this upcoming year about some of the positive beneficial effects of interbreeding," Hammer said. "We've been working on it, and I know others are, too."

The ancestor of the human lineage?

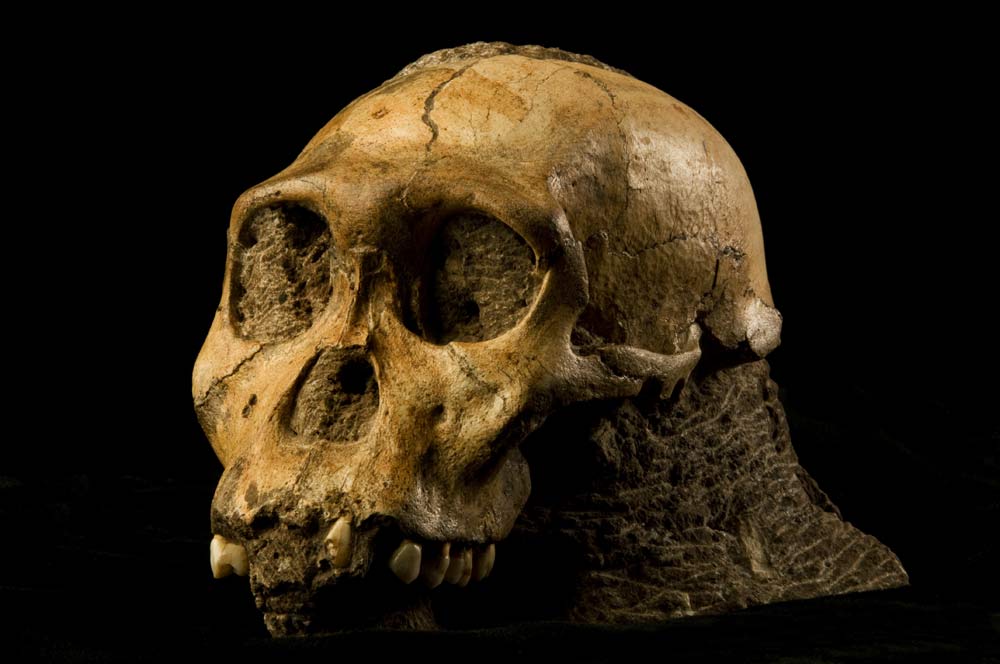

A startling mix of human and primitive traits seen in the brains, hips, feet and hands of the extinct hominid known as Australopithecus sediba makes a strong casefor this species being the immediate ancestor to the human lineage, researchers said this year.

The nearly 2-million-year-old A. sediba, discovered in South Africa, was first revealed last year. Australopithecus means "southern ape," and is a group that includes the iconic fossil Lucy, while sediba means "wellspring" in the South African language Sotho.

The fossils display a mix of both human and more primitive features that hint it might be an intermediary form between Australopithecus and Homo, our lineage. For instance, it had a small brain compared with that of humans, but it had a relatively large brain region directly behind the eyes just as we do, one linked with higher mental functions such as multitasking. And like us, the specimen had hands equipped with a long thumb that might have been useful for tool-making, and a broad pelvis that might have later helped accommodate larger-brained offspring.

Out of Arabia?

Arabia was a legendary crossroads between the East and West for centuries, and this year research suggests it might have been pivotal at the dawn of history as the spot from which modern humans left Africa to expand across the rest of the world. [Photos: Our Closest Human Ancestor]

When and how modern humans dispersed out of Africa has long proven controversial, but past evidence had suggested an exodus along the Mediterranean Sea or Arabian coast some 60,000 years ago. However, stone artifacts unearthed in the Arabian Desert at least 100,000 years old now suggest modern humans first left Africa by at least 40,000 years earlier than researchers had expected.

Although the interior of the Arabian Peninsula is now a relatively barren desert, when these artifacts were made, copious rain fell across the area, making it a verdant paradise rich in resources. This is likely why humans leaving Africa traveled across Arabia instead of hugging the coast.

"I hope that our findings will stimulate research in South Asia — India in particular — to find the remains of early anatomically modern humans in that part of the world,"archaeologist Hans-Peter Uerpmann from Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen, Germany, told LiveScience.

"Our focus this year will be on gathering evidence to reconstruct the paleoclimate in southern Arabia during the ice age that lasted between 75,000 and 60,000 years ago," paleolithic archaeologist Jeffrey Rose at the University of Birmingham in England told LiveScience. This will help researchers determine how friendly or hostile the climate was back then "to help understand the fate of these early humans on the Arabian Peninsula."

If these ancient peoples eventually died off in Arabia, they would just be a failed migration out of Africa. However, if they survived, they may be the ancestors "to all non-African people living on Earth," Rose said. "Only further exploration throughout Arabia will answer these questions."

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus