Sex with Neanderthals Gave Humans Immunity Boost

Neanderthals and other extinct humans might have endowed some of us with the robust immune systems we enjoy today, scientists now find.

These genetic gifts might have helped our species as we expanded out of Africa, investigators added.

Although we modern humans are the only surviving members of our lineage, others once roamed the Earth, including familiar Neanderthals and the newfound Denisovans, who lived in what is now Siberia. Genetic analysis of fossils of these extinct lineages has revealed they once interbred with our ancestors, with recent estimates suggesting that Neanderthal DNA made up 1 percent to 4 percent of modern Eurasian genomes and Denisovan DNA made up 4 percent to 6 percent of modern Melanesian genomes. [DNA Evidence: Neanderthals Had Sex with Humans]

Disease-fighting genes

To learn more about what effects such mingling might have had on our evolution, researchers focused on so-called HLA genes, which help our immune systems defend our bodies, and have been found in one Denisovan and three Neanderthal specimens. Now, the scientists have discovered variants of these genes that apparently originated in Denisovans and Neanderthals made their way into modern Eurasian and South Pacific populations.

Originally, the researchers were investigating HLA genes for the role they play in whether or not the body rejects tissue transplants. The last variant of HLA that they sequenced, called HLA-B*73, "surprised us by having an exceptionally unusual sequence, suggesting it might have an archaic origin," researcher Peter Parham, an immunogeneticist at Stanford University, told LiveScience.

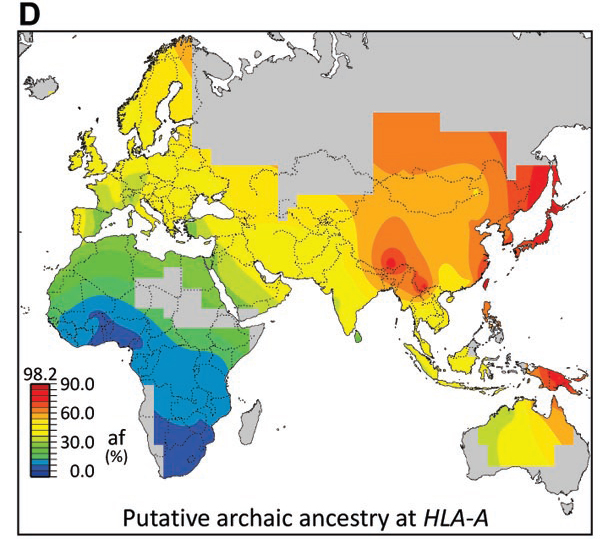

The investigators suggest that modern humans, on their way out of Africa, acquired this odd variant from the Denisovans in west Asia, , which may have helped whoever had it against the local germs in the area at the time. Another HLA gene variant, called HLA-A*11, is absent from African populations, but represents up to 64 percent of versions of the gene in East Asia and Oceania, with the greatest frequency in people from Papua New Guinea.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A similar situation is seen in some HLA gene types found in the Neanderthal genome. These variants are common in European and Asian populations, but rare in African populations. "We are finding frequencies in Asia and Europe that are far greater than whole genome estimates of archaic DNA in modern human genomes, which is 1 to 6 percent," said Parham. Within one class of the HLA genes, the researchers estimate that Europeans owe half of their variants to interbreeding with Neanderthals and Denisovans, Asians owe up to 80 percent and Papua New Guineans up to 95 percent. "The likely interpretation was that these HLA class variants provided an advantage to modern humans and so rose to high frequencies," Parham said.

Where we came from

This discovery could add fire to a long and vigorous debate in human evolution between the out-of-Africa model and the multiregional model, with the out-of-Africa model suggesting anatomically modern humans of African origin conquered the world by completely replacing archaic human populations about 100,000 years ago. The multiregional model suggests anatomically modern humans emerged from interbreeding between widespread human populations, including ones that first left Africa more than 1 million years ago.

All this new genetic evidence suggests a different picture. Although modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans share a common ancestor in Africa, the groups split into separate, distinct populations approximately 400,000 years ago. The Neanderthal lineage migrated northwestward into West Asia and Europe, and the Denisovan lineage moved northeastward into East Asia. The ancestors of modern humans stayed in Africa until 65,000 years or so ago, when they expanded into Eurasia and then encountered the other human groups. [See map of HLA distribution]

"Our study has the potential to be criticized by protagonists of both theories, because it offers a compromise between them," Parham said. "We show how this vital aspect of the human immune system has evolved in a multiregional fashion but on a genomic background that appears largely out-of-Africa."

Not only might this study of immune system genes from extinct lineages shed light on modern humans, but "the same is likely to be true for the reproductive system and the nervous system," Parham added. "The power of future studies will be enhanced by the study of larger numbers of Neandertal and Denisovan individuals, as well other species and populations of Homo." (Neandertal is the modern German spelling of Neanderthal.)

The researchers detailed their findings online Aug. 25 in the journal Science.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.