In Photos: New Human Ancestor Possibly Unearthed in Spanish Cave

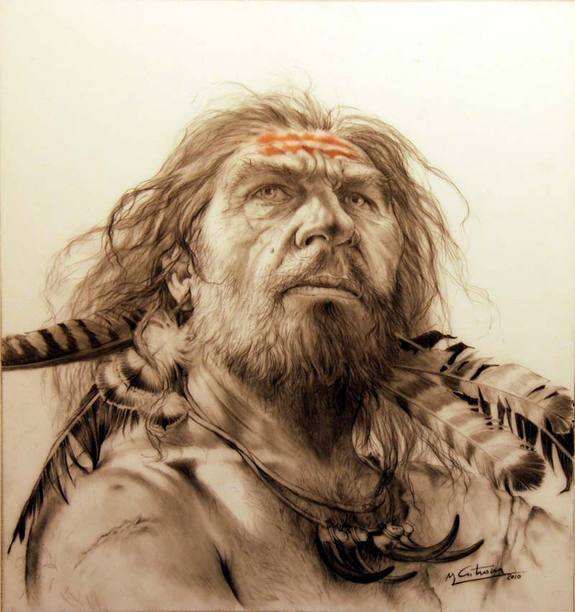

Mysterious Ancestor?

The oldest known human DNA found yet reveals human evolution was even more confusing than before thought, researchers say. The genetic material came from the bone of a hominin living in what is now the Sima de los Huesos in Northern Spain approximately 400,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene.

Old Thigh

The thighbone of the 400,000-year-old hominid from Sima de los Huesos, Spain.

Hominid Bones

Here, a skeleton of a Homo heidelbergensis from Sima de los Huesos, a unique cave site in Northern Spain.

Pit of Bones

The human thighbone was unearthed in the Sima de los Huesos, or "Pit of Bones," an underground cave in the Atapuerca Mountains in Northern Spain. This Pit of Bones has yielded fossils of at least 28 individuals, the world's largest collection of human fossils dating from the Middle Pleistocene about 125,000 to 780,000 years ago.

Digging Deep

The Sima de los Huesos is located about 100 feet (30 meters) below the surface at the bottom of a 42-foot (13-meter) vertical shaft. Archaeologists suggest the bones may have been washed down it by rain or floods, or that the bones were even intentionally buried down there.

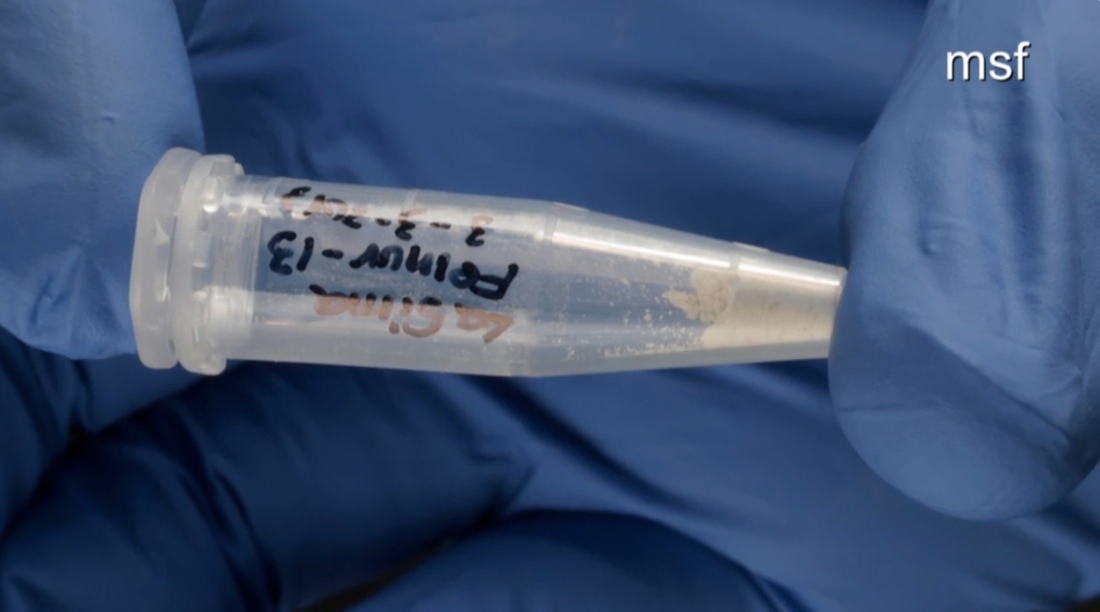

Bone Sample

The researchers reconstructed a nearly complete genome of this thighbone fossil's mitochondria — the powerhouses of the cell, which possess their own DNA and get passed down from the mother.

Neanderthal?

The fossils unearthed in the Sima de los Huesos cave resembled Neanderthals, so researchers expected this mitochondrial DNA to be Neanderthal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

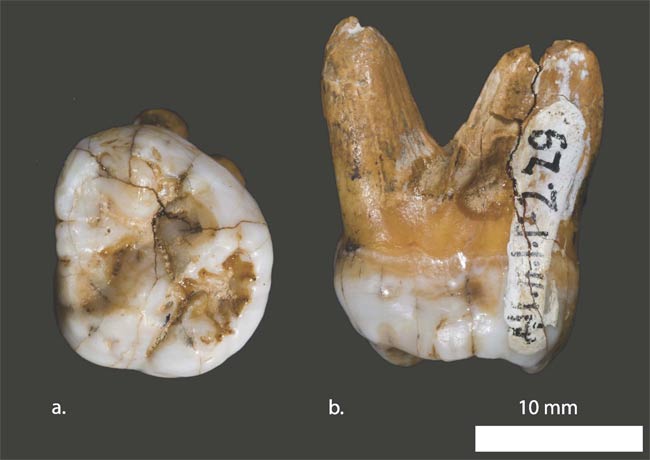

Denisovan?

Surprisingly, the mitochondrial DNA reveals this fossil shared a common ancestor not with Neanderthals, but with Denisovans, splitting from them about 700,000 years ago. This is odd, since research currently suggests the Denisovans lived in eastern Asia, not in western Europe where this fossil was uncovered. The only known Denisovan fossils so far are a finger bone and a molar found in Siberia.

More Bone Needed

The scientists now hope to learn more about these fossils by retrieving DNA from their cell nuclei, not their mitochondria. However, this will be a huge challenge — the researchers needed almost 2 grams of bone to analyze mitochondrial DNA, which outnumbers nuclear DNA by several hundred times within the cell.