Computers Piece Together Scattered Medieval Scrolls

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

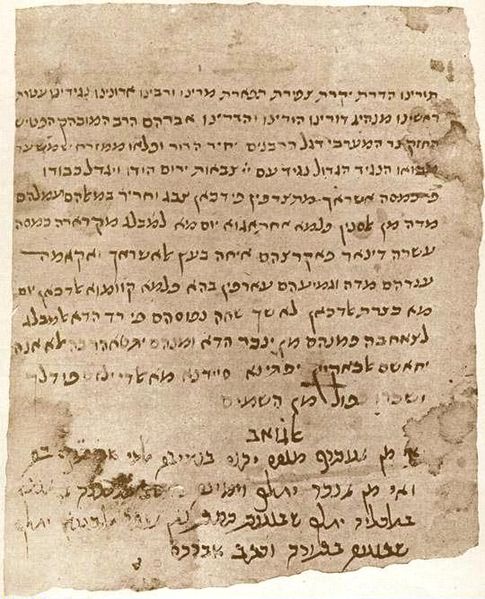

It's like something out of "The Da Vinci Code": Hundreds of thousands of fragments from medieval religious scrolls are scattered across the globe. How will scholars put them back together?

The answer, according to scientists at Tel Aviv University, is to use computer software based on facial recognition technology. But instead of recognizing faces, this software recognizes fragments thought to be part of the same work. Then, the program virtually "glues" the pieces back together.

This enables researchers to digitally join a collection of more than 200,000 fragmentary Jewish texts, called the Cairo Genizah, found in the late 1800s in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo. The Cairo Genizah texts date from the ninth to the 19th centuries, and they're dispersed amongst more than 70 libraries worldwide. Researchers will report on their progress in digitally reuniting the Cairo Genizah during the second week in November at the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision in Barcelona.

Genizahs are storerooms for holy texts, which under Jewish law cannot be simply tossed in the garbage when they're worn out. The Cairo Genizah, however, also contains merchants' lists, divorce documents and even personal letters, a firsthand look at hundreds of years of history in the Middle East.

A non-profit organization, the Friedberg Genizah Project, is working to digitize the fragments of the Cairo Genizah. Meanwhile, Tel Aviv University computer scientists Lior Wolf and Nachum Dershowitz have the difficult task of joining the fragments into a continuous whole.

To do so, they developed a computer program that analyzes document handwriting, physical properties of the page, and even spacing between the lines of writing.

"Its big advantage is that it doesn't tire after examining thousands of fragments," Wolf said in a statement. The program has made 1,000 confirmed connections between fragments of the Cairo Genizah in the span of a few months, almost the same amount made in 100 years of human scholarship.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers are now applying the same technology to fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of hundreds of text found along the Dead Sea in the 1950s.

"It's a more complicated challenge," Wolf said, referring to the Dead Sea Scrolls. "The fragments are for the most part much smaller, and many of the texts are very unique. These texts shed light on the beginnings of Christianity."

Wolf and Dershowitz's effort is part of a Google project using high-resolution photographs of the Dead Sea Scrolls in order to put these biblical texts online.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus