Asteroids May Have Brought Precious Metals to Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

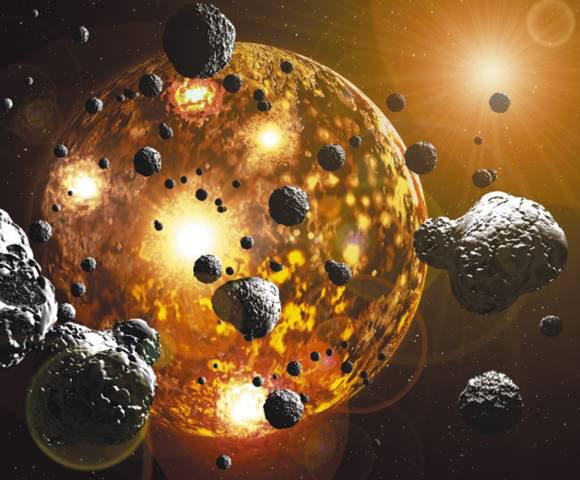

The precious metals that we see on Earth today may be largely heavenly in nature, coming from the sky billions of years ago, scientists now find.

Back when the Earth was just forming, the materials that make up the planet were combining and differentiating into layers by weight — lighter materials floated to the surface and now make up Earth's crust, while heavier materials such as iron sank to the planet's interior.

Our understanding of planet formation suggested that precious metals such as gold and tungsten should have moved into Earth's iron core long ago, due to the affinity they have for bonding with iron. Surprisingly, precious metals instead appear relatively abundant on the planet's surface and in the underlying mantle layer. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

To help resolve this discrepancy, scientists investigated ancient rocks from Isua, Greenland, to see how the planet changed over time and when precious metals entered the picture. Their analysis revealed that the composition of the Earth changed dramatically about 3.9 billion years ago. This violent era was known as the Late Heavy Bombardment, when hordes of asteroids smashed into Earth and the other inner planets — the aftermath of this onslaught is still evident in the many craters that litter the surface of the moon.

Those hordes of asteroids brought with them a bevy of precious metals.

"This is the process by which we have most of the precious elements accessible on Earth today," researcher Matthias Willbold, a geologist at the University of Bristol in England, told OurAmazingPlanet.

Willbold and his colleagues concentrated on investigating the ancient Greenland rocks for isotopes of tungsten, a metal that, like gold, has an affinity for bonding with iron. Isotopes of tungsten each have 74 protons in their atoms but different numbers of neutrons — tungsten-182 has 108 neutrons, while tungsten-184 has 110.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the scientists compared modern rocks with Greenland samples that predated the Late Heavy Bombardment, they discovered the ratio of tungsten-182 to tungsten-184 is 13 parts-per-million lower in modern rocks. Willbold and his colleagues say this difference suggests that much of the tungsten and precious metals seen in modern rocks came from meteor strikes. (Primitive meteorites are known to have significantly depleted levels of tungsten-182 compared to tungsten-184).

The scientists posit that these meteor strikes may also have triggered the flow of hot rock in the upper layer of the mantle right below the Earth's crust that is seen up to the present day.

"We want to measure more ancient samples to see how the mantle might have changed over time," Willbold said.

The researchers detail their findings in the (Sept. 8) issue of the journal Nature.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus