Debate heats up over swimming ability of bizarre-looking Spinosaurus

Maybe the dinosaur Spinosaurus wasn't the Michael Phelps of swimming.

The wild-looking Spinosaurus may not have been the Michael Phelps of dinosaurs, as was recently claimed, but rather more like a casual bathing beauty that preferred to wade gracefully in the shallow zone, a new study suggests.

That's not to say Spinosaurus couldn't swim: It could. But it wasn't the "highly specialized aquatic predator" that could efficiently chase prey through the water, as it was made out to be in a big 2020 study published in the journal Nature, the researchers of the new study said.

"Spinosaurus was probably a decent swimmer, and certainly a better swimmer than any other known large theropod [bipedal, mostly meat-eating dinosaurs]," study co-researcher Thomas Holtz, principal lecturer in vertebrate paleontology at the University of Maryland, told Live Science in an email. "But being a swimmer isn't the same thing as being a specialized aquatic pursuit predator."

Rather, Spinosaurus was probably like a modern-day heron or stork — wading into the water and sticking part of its head underwater as it fished for prey, but also opportunistically hunting on land for terrestrial animals or winged creatures, the researchers said.

Related: Photos: Dinosaurs sloshed around ancient lagoon

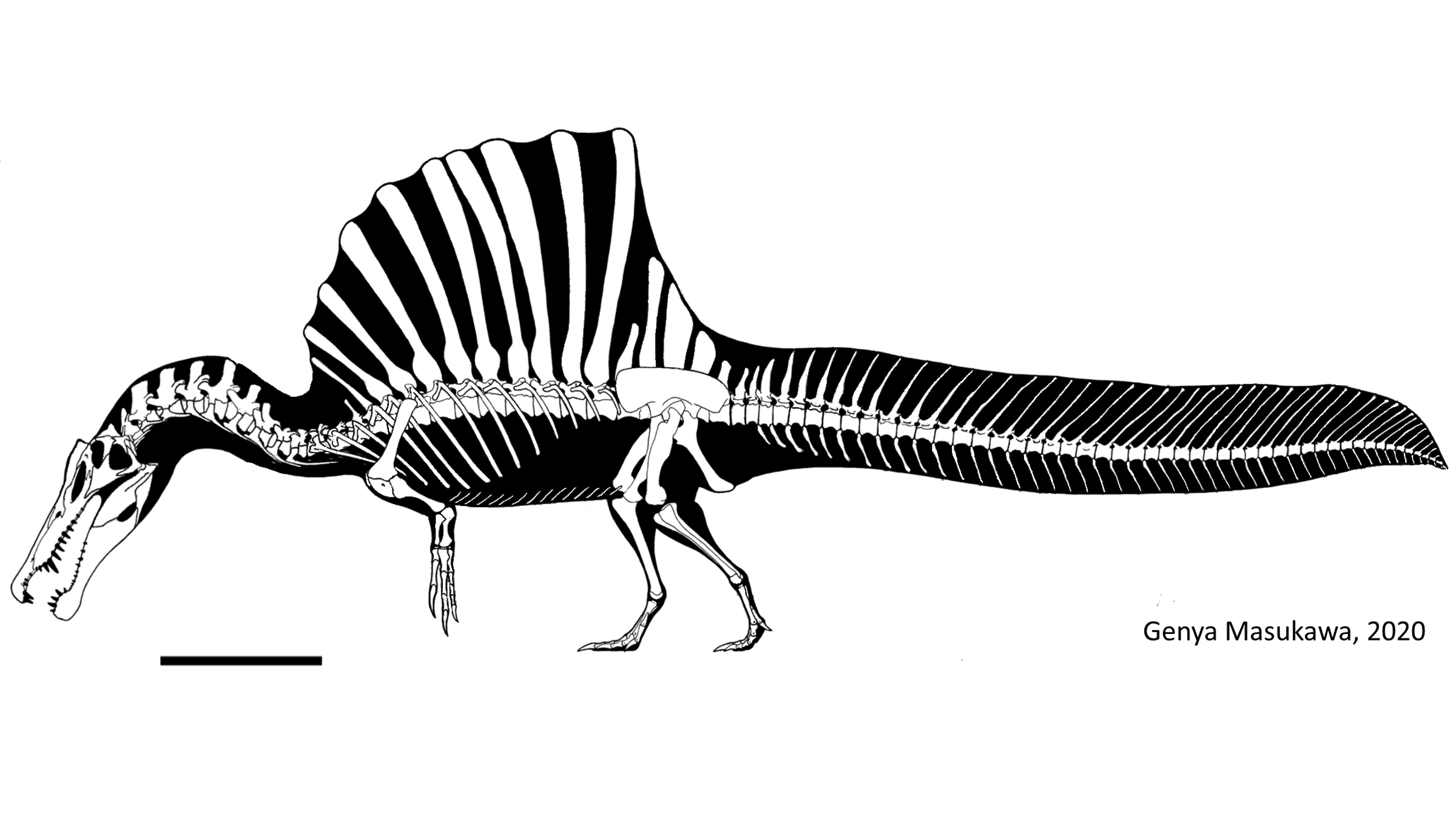

Spinosaurus, which lived about 112 million to 94 million years ago during the Cretaceous period, has baffled scientists since its 1915 discovery in North Africa. At more than 50 feet (15 meters) in length, it was as large as a Tyrannosaurus rex and had large projections sticking out of its back, which may have formed a skin-covered sail. The oddball's crocodile-like snout and teeth indicated that it hunted fish; chemical analyses of isotopes (versions of an element) and fossil finds confirmed it ate fish as well as snacked on dinosaurs and pterosaurs.

Spinosaurus' habits are challenging to decipher because there are few fossils of the beast. The most complete skeleton, from Egypt, was destroyed in 1944 when the Allies bombed a museum in Munich, Germany. In the past decade or so, new fossil discoveries have led to a slew of studies on Spinosaurus, triggering renewed interest in understanding its lifestyle, said Darla Zelenitsky, an assistant professor of paleontology at the University of Calgary, who was not involved in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Discover the Dinosaurs: $22.99 at Magazines Direct

Journey back to the age of dinosaurs with Live Science and uncover the secrets of some of the prehistoric world’s most remarkable beasts. From the Tyrannosaurus rex and Diplodocus to the Triceratops and Coelophysis, get up close and discover how these fascinating creatures lived, hunted, evolved and ultimately died out. Why did Stegosaurus travel in herds? Is it possible to clone a dinosaur? Find the answers to these questions and many more.

Champion or mediocre swimmer?

The researchers took a deep dive into Spinosaurus' anatomy, habitat and diet, and also compared these with the features of other animals, both living and extinct.

So, what about Spinosaurus negates the "Olympic swimmer" claim? The new analysis suggested its weird body shape, especially its tall sail, would have created a lot of drag in the water. "Our rough estimate shows it would [have needed] to be many meters under the water to reduce the drag effect," Holtz said. "But as Spinosaurus is known from estuarine [swampy] environments, it was feeding not just in huge Mississippi- or Amazon-like channels, but in water of all depths."

Moreover, Spinosaurus' body shape didn't look like that of other aquatic pursuit hunters.

"Most larger pursuit predators — from Jurassic ichthyosaurs to tunas to dolphins and so on — have relatively stiff bodies and short necks, with the propulsion generated from a rather concentrated area of motion in the tail," Holtz said. But Spinosaurus didn't have a short neck or a stiff body. "In contrast, the body of Spinosaurus is more like less specialized swimmers. And the fact that isotopic evidence shows they were also feeding on land strongly supports them as having a more generalized lifestyle rather than one committed to a single primary mode of life," Holtz said.

Spinosaurus had a relatively long neck that was curved like a coat hanger. "It's got this weird neck ... for stabbing down," added study lead researcher David Hone, a senior lecturer of zoology at Queen Mary University of London. Plus, its nostrils were halfway up its snout, not on top of its snout like a crocodile's. "That makes sense if you hold your nose just under the surface [while hunting]," rather than spending all its time mostly submerged, Hone told Live Science.

Other anatomical clues hint that Spinosaurus was more like a stork than a leviathan — Hone detailed many on Twitter, including that propulsion from long tails, like that of Spinosaurus, usually helps with short bursts, not lengthy pursuits, Hone said. The 2020 Nature study also showed that Spinosaurus couldn't swim as efficiently as a crocodile, in part because it had fewer tail muscles than crocs.

Perhaps, Spinosaurus' tail had other purposes besides swimming — it could have been a dinosaur-age billboard, for example, used to send social-sexual signals, the researchers said. For instance, an elephant uses its tusks for many purposes, such as attracting mates, defending itself, digging and lifting objects, they said.

But other paleontologists say that more research on Spinosaurus is needed to suss out its past. "Both studies have their merits, and I suspect that this is not the end of the lifestyle controversy for Spinosaurus," Zelenitsky said.

Related: Image gallery: 25 amazing ancient beasts

"So what's next for Spinosaurus? Who knows?" Lindsay Zanno, head of paleontology at North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and associate research professor at North Carolina State University, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "But if it were me, I'd look more closely at the internal structure of the skeleton." The microscopic structure of the bone could reveal whether it floated well, Zanno noted.

Meanwhile, the lead author of the 2020 study is standing by his interpretation that Spinosaurus was a specialized predator of aquatic prey. "Long story short, it doesn't really change anything for us — there is nothing in the paper we have not considered before," Nizar Ibrahim, a senior lecturer of paleontology at the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom, told Live Science in an email.

The new study was published in the January issue of the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.