1st known swimming dinosaur just discovered. And it was magnificent.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Despite old, out-of-date drawings of long-necked dinosaurs wading in swamps, scientists have long believed that dinosaurs were a land-loving bunch: None were thought to swim. Now, though, a new tail fossil found in Morocco reveals that the sharp-toothed and fearsome Spinosaurus aegyptiacus was the Michael Phelps of the Cretaceous.

The predatory Spinosaurus, which could grow up to 23 feet (7 meters) long, had a broad, paddle-like tail that behaved more like the tails of today's crocodiles than that of other carnivorous dinosaurs, researchers reported today (April 29) in the journal Nature.

"This discovery is the nail in the coffin for the idea that non-avian dinosaurs never invaded the aquatic realm," Nizar Ibrahim, a paleontologist at the University of Detroit Mercy and the lead author of the new study, said in a statement. "This dinosaur was actively pursuing prey in the water column, not just standing in shallow waters waiting for fish to swim by."

Related: Paleo-Art: Dinosaurs come to life in stunning illustrations

Swimming spinosaurids

Spinosaurus has always been a controversial creature. It was a theropod, or part of a group of mostly carnivorous dinosaurs that walked on two legs; and it was around the size of another theropod, Tyrannosaurus rex, with massive projections of its vertebrae towering up to 5.4 feet (1.6 m) above its back. Paleontologists think these projections probably supported a skin-covered sail. Given its long snout and cone-shaped teeth, which look much like modern crocodiles', paleontologists have long been confident that Spinosaurus ate fish, but most suspected that it waded along shorelines, hunting in shallow waters.

Ibrahim and his colleagues thought Spinosaurus was more than just a wader. In 2014, the researchers published a paper in the journal Science arguing that the dinosaur was adapted for a heavily aquatic lifestyle. It had flat feet and nostrils high on its head, as well as dense bones that would have allowed it to control its buoyancy while swimming, they wrote at the time. But, they wrote in the new Nature paper, this idea was challenged, especially because there was no evidence to show how Spinosaurus would have propelled itself through water.

Related: Images: Digging up an aquatic dinosaur called Spinosaurus

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A particular sticking point was the blank space on Spinosaurus' skeleton where its tail should have been. There is only one existing skeleton of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus that is mostly complete, Ibrahim and his colleagues wrote. Other known skeletons of the species were housed in Munich, Germany, during World War II and were destroyed by bombings. The remaining specimen was missing much of the tail and vertebral sections.

New discovery

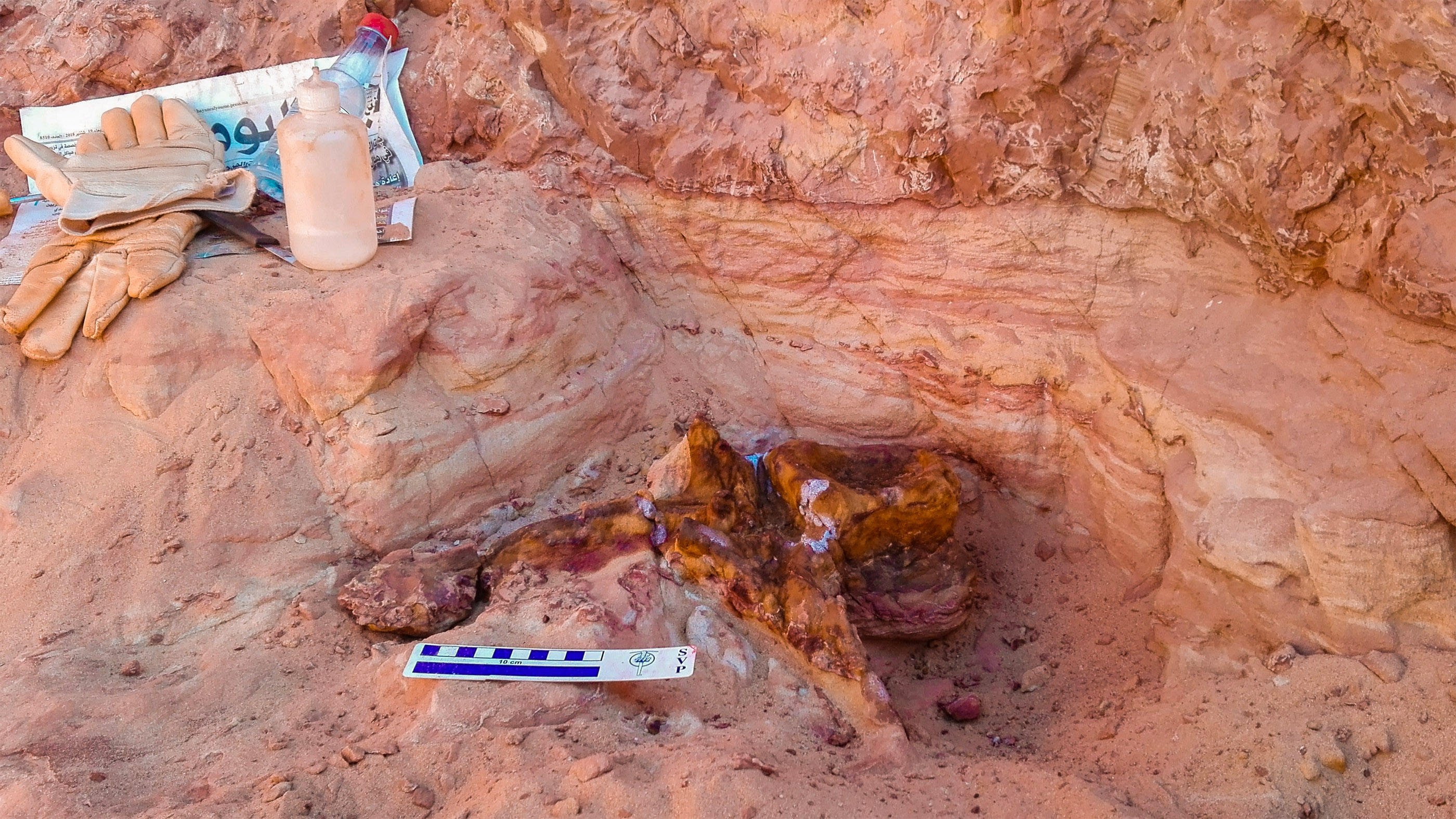

A new fossil, discovered in the Kem Kem beds of southeastern Morocco, changed all that. Ibrahim and his team unearthed bones making up about 80% of the length of the tail of a young Spinosaurus.

And the tail looked nothing like that of other theropod carnivores. It was tall and flat, like a fin. To test how the tail would have performed in the water, the researchers created a plastic model of the tail and attached it to a robotic controller. They found that the tail generated eight times more thrust in the water than the tails of two other theropods — Allosaurus and Coelophysis, a small Triassic carnivore. It was also 2.6 times more efficient in its movement than the tails of those two land-based dinosaurs. Instead, it behaved more like the tails of a modern crocodile or modern crested newt, two aquatic animals that can also move on land.

The findings landed with a splash in the paleontological community on Wednesday (April 29).

"This tail, to me, looks very aquatic," Jason Poole, a paleontologist and adjunct professor at Drexel University who was not involved in the research, told CNN.

But despite its swimming prowess, Spinosaurus probably didn't stray too far from land, University of Edinburgh paleontologist Steve Brusatte, who also was not involved in the study, told Gizmodo.

"No doubt Spinosaurus was an able swimmer in shallow waters, but its fossils are also found inland, so it probably was comfortable on land and in water," Brusatte said.

- Gory guts: Photos of a T. rex autopsy

- In images: Tyrannosaur trackways

- Image gallery: Tiny-armed dinosaurs

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus