Tiny Triassic critter provides new insight into the evolution of 1st flying reptiles

It likely walked on its tippy toes and ate insects.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

More than a century ago, researchers unearthed the remains of a tiny, ancient reptile from inside a swath of sandstone in northeastern Scotland. Most of its skeleton was long gone, but scientists recently reconstructed the animal for the first time, identifying it as a reptilian predecessor of pterosaurs — the first reptiles to achieve powered flight.

For decades, paleontologists debated exactly how to categorize this 7-inch-long (20 centimeters) specimen from the Triassic period (252 million to 201 million years ago), which was first described in 1907 and named Scleromochlus taylori. In a new study, published Wednesday (Oct. 5) in the journal Nature, scientists finally set the record straight, placing it in a group that includes pterosaurs as well as other early reptiles.

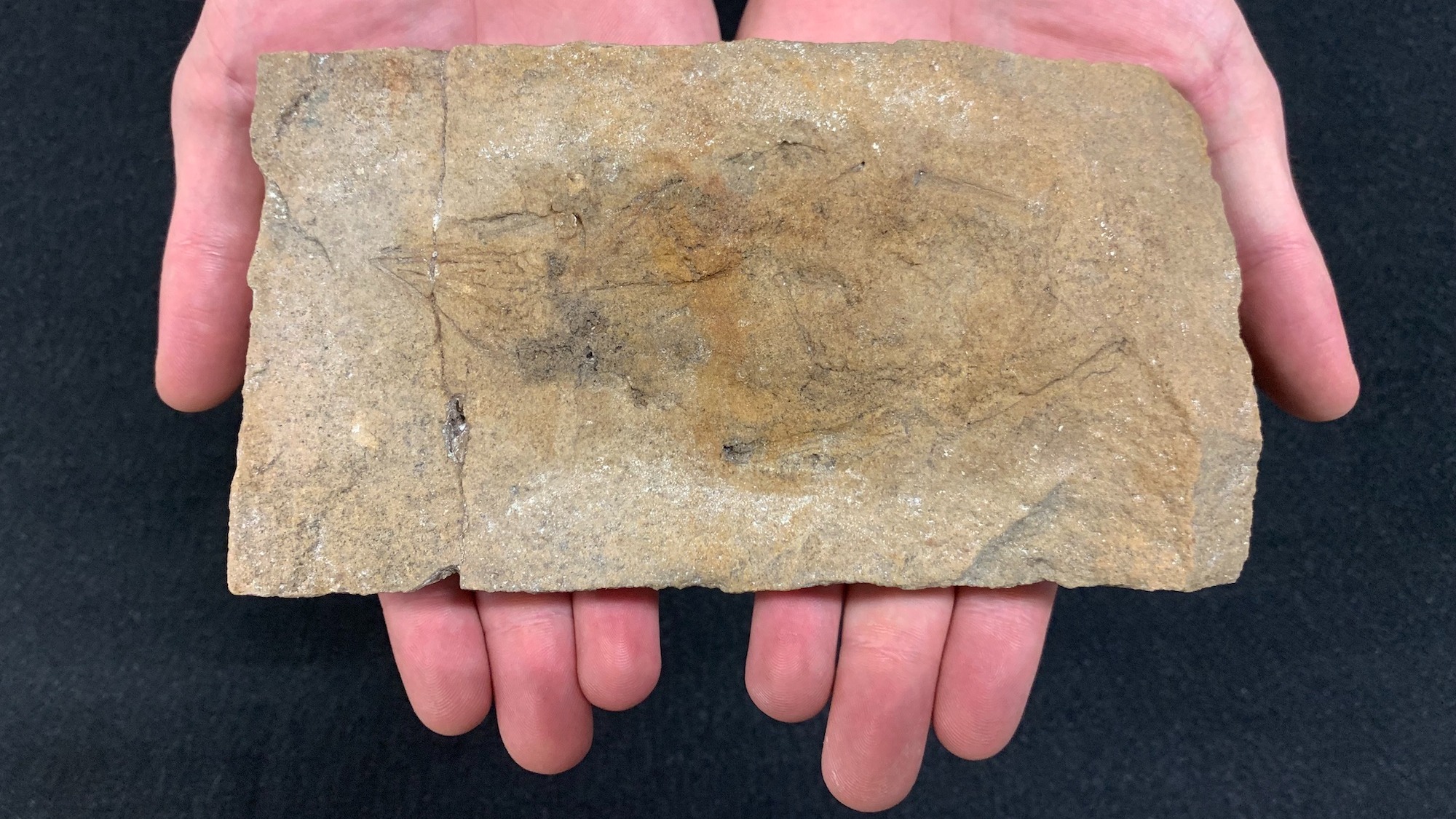

Using computerized tomography — CT scans — a team of scientists from the University of Birmingham in England and Virginia Tech digitally modeled the first complete skeletal reconstruction of S. taylori. Though some of its bones were missing, an impression of the animal's skeleton was preserved in the rock. This offered some clues about what the animal might have looked like, but the specimen was nonetheless difficult to classify.

"There were ongoing debates about where it fit [into the evolutionary tree]," lead study author Davide Foffa, a research associate at National Museums Scotland and a research fellow at the University of Birmingham, told Live Science. "Scientists thought it was a close relative of either pterosaurs or dinosaurs, or reptiles such as crocodylians, amongst many other things. However, the scans showed minute details not available in prior studies."

Those details included a better picture of the animal's femur and upper jaw. Before digital modeling was available, scientists would use clay or other malleable materials to create a cast of delicate fossils. However, some parts of this specimen were too small or narrow to provide an adequate impression.

Related: Largest Jurassic pterosaur on record unearthed in Scotland

"The preservation is very odd since some of the bones are completely washed away, and what we have left is a block of sandstone with the impression of where the bones once were," Foffa said. "It has been studied a lot, but the problem was we couldn't reach all of the cavities in the impression and see where some of the bones were still connected."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Foffa said that the sandstone block essentially served as a "natural mold" of the specimen, though it provided an incomplete picture of the ancient creature's appearance.

"With two [impression] halves, we lose the 3D orientation, and some of the bones were split between the two blocks," Foffa said. "It was difficult to understand the shape, size and dimensions of the specimen, and the impressions only captured part of it."

"Once we placed it," Foffa said, "other details showed that the Scleromochlus was similar, but not a direct ancestor [to either dinosaurs or pterosaurs] and that it is anatomically more similar to lagerpetids than to pterosaurs."

The researchers also concluded that S. taylori likely ate small insects and stood on its tippy toes but had the potential to walk on all fours when necessary, and that its posture was unlike that of frogs and lizards, which typically have a sprawling posture and move with all four limbs in contact with the ground.

However, the study supports the idea that the first flying reptiles evolved from small ancient reptiles like S. taylori.

This led scientists to conclude that S. taylori likely belonged to the group Pterosauromorpha ("pterosaurlike forms"), which includes pterosaurs — the first animals with bones that evolved powered flight — and lagerpetids, bipedal reptiles that were the size of a cat or a small dog, according to the study. Scleromochlus was a lagerpetid that predated pterosaurs and was not a direct ancestor of the reptilian flyers, though "pterosaurs evolved from tiny, ground-living, fast-running reptiles," that probably resembled Scleromochlus, the researchers reported.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus