Missing link in pterosaur origins discovered

Until now, the pterosaur family tree was unclear.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Nearly nothing is known about the family tree of pterosaurs — iconic reptiles that flew alongside the dinosaurs. These now-extinct beasts appear in the fossil record with already developed wings and senses adapted for flying, with researchers having nary a clue about their immediate evolutionary history.

But now, the pterosaur's family tree has a new branch; an enigmatic group of small reptiles, known as lagerpetids, might be the closest-known pterosaur relatives on record, the researchers of a new study say.

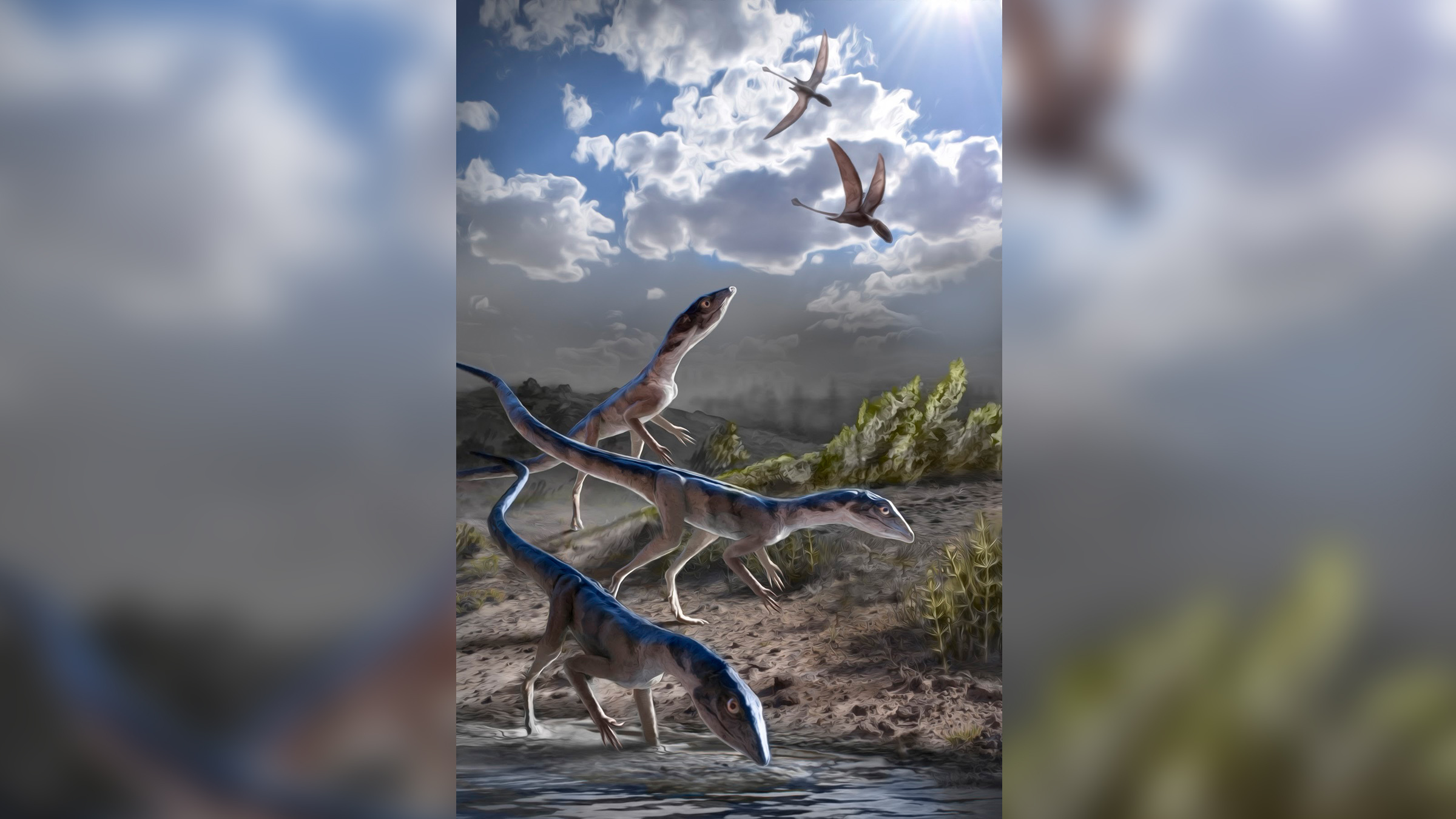

Unlike pterosaurs, however, lagerpetids did not fly. "Now, we have an idea of what a flightless pterosaur relative would look like," study co-researcher Sterling Nesbitt, an associate professor of geosciences at Virginia Tech, told Live Science.

Related: Photos: Baby pterosaurs couldn't fly as hatchlings

The first pterosaur fossils were described in 1784, and countless pterosaur remains have turned up since then, dating as far back as 220 million years during the Triassic period to about 65 million years ago, at the end-Cretaceous extinction. But beyond knowing that pterosaurs were archosaurs, a group that includes dinosaurs, birds and crocodylians, scientists haven't figured out the pterosaur's immediate ancestors — animals that could offer clues about how the pterosaur became the first vertebrate to evolve powered flight.

Although lagerpetids were Earth-bound, they do shed light on pterosaur flight, Nesbitt said. Researchers have published studies on lagerpetid fossils since the 1970s, but they didn't know much about this weird reptile, except that it lived from about 237 million to 210 million years ago, and that it was likely related to dinosaurs, which first appeared about 233 million years ago. After all, the lagerpetid hindlimb and pelvis did resemble that of a dinosaur, Nesbitt said. But then, researchers started finding more complete lagerpetid fossils in more places around the world, including a 237 million-year-old "tiny bug slayer" from Madagascar, and realized that these animals shared more in common with pterosaurs than with dinosaurs.

In addition, researchers used a micro-CT (computed tomography) scan to analyze a lagerpetid braincase, where the brain sat. The results showed that lagerpetids and pterosaurs had similarly shaped brains and inner ears, so some of the pterosaur's specialized sensory systems likely evolved before powered flight.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It has to do with the semicircular canals [in the ear], which orients you in 3D space," Nesbitt said. "The shape of those canals correlates with ecology and how you move your head — basically, are you agile or not? And a lot of things that have flight have semicircular canals with a really large and characteristic [shape] because you're flying, you're in a lot more 3D space."

Lagerpetids, however, are not the direct ancestors of pterosaurs. If you think of a family tree shaped like a "Y," the lagerpetids and pterosaurs are on different "arms" of the Y, but share a common ancestor at the Y's base.

The study "provides some impressive evidence," but "some difficult questions remain," said David Unwin, a reader in paleobiology at the University of Leicester in England who studies pterosaurs, but wasn't involved with the study.

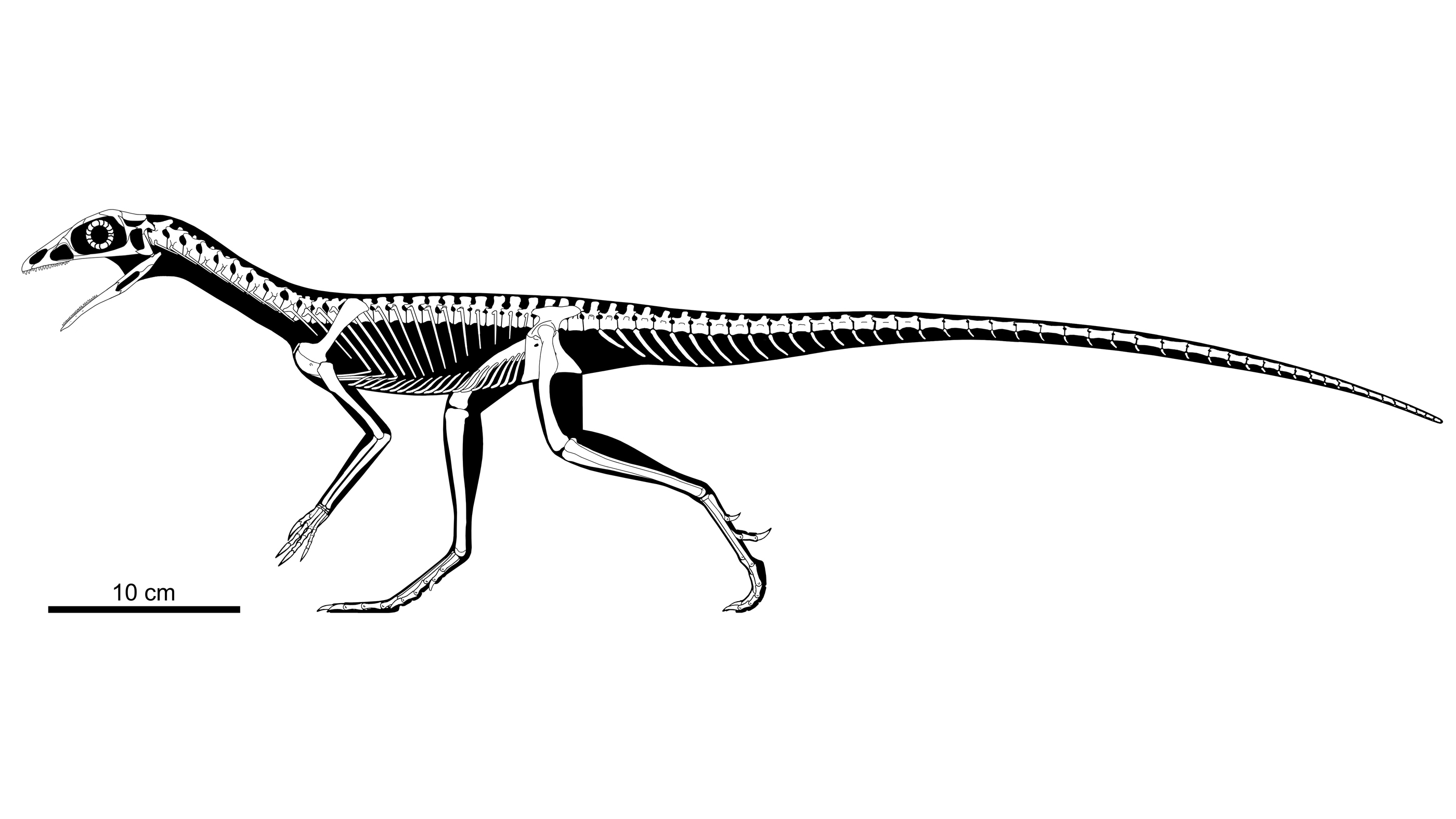

"Lagerpetids, argued in this analysis to be the closest known relatives to pterosaurs, were small, lightly-built, fully bipedal [two-legged] animals with relatively short forelimbs," Unwin told Live Science in an email. "Pterosaurs, by contrast, were fully quadrupedal [four-legged] and had highly elongate[d] forelimbs." In other words, there's a huge difference in the body shapes of lagerpetids, pterosaurs and dinosaurs, and "these discoveries throw little light on when, where and how pterosaurs and their flight ability first evolved," Unwin said.

The study was published online Wednesday (Dec. 9) in the journal Nature.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus