Photos: Baby pterosaurs couldn't fly as hatchlings

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Introduction

An analysis of 16 baby pterosaur embryos found in northwestern China shows that these little reptiles likely couldn't fly once they hatched. That is, they could probably walk after breaking through their eggs, but couldn't immediately take to the skies.

The discovery comes from a site with 215 pterosaur eggs and the fossilized remains of older pterosaurs. The finding suggests that this species of pterosaur, known as Hamipterus tianshanensis, had colonial nesting behavior. [Read more about the pterosaur egg discovery]

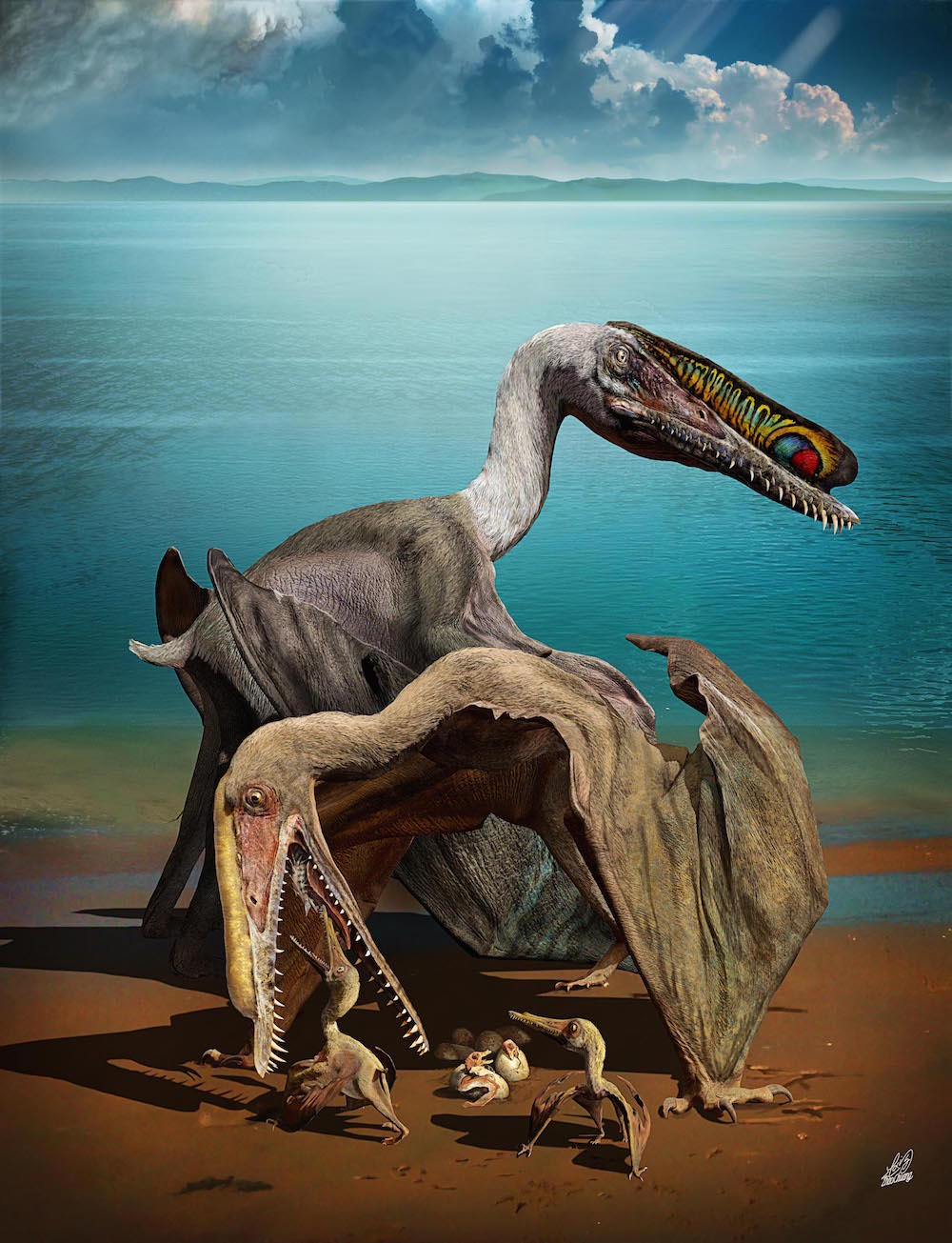

Parent pterosaurs

An artist's interpretation of Hamipterus tianshanensis with its young. Because the reptiles likely couldn't fly upon hatching from their eggs, they probably needed parental care.

Pterosaur bonebone

Researchers found the pterosaur eggs and fossils in a bone bed (literally, a site with many bones) in the Hami region of northwest Xinjiang, China.

Jawbone

The lower jaw of the pterosaur Hamipterus tianshanensis. Notice the large teeth. In contrast, the H. tianshanensis embryos did not have teeth yet, the researchers found.

Small jaw

An incomplete pterosaur lower jaw, likely belonging to a young animal.

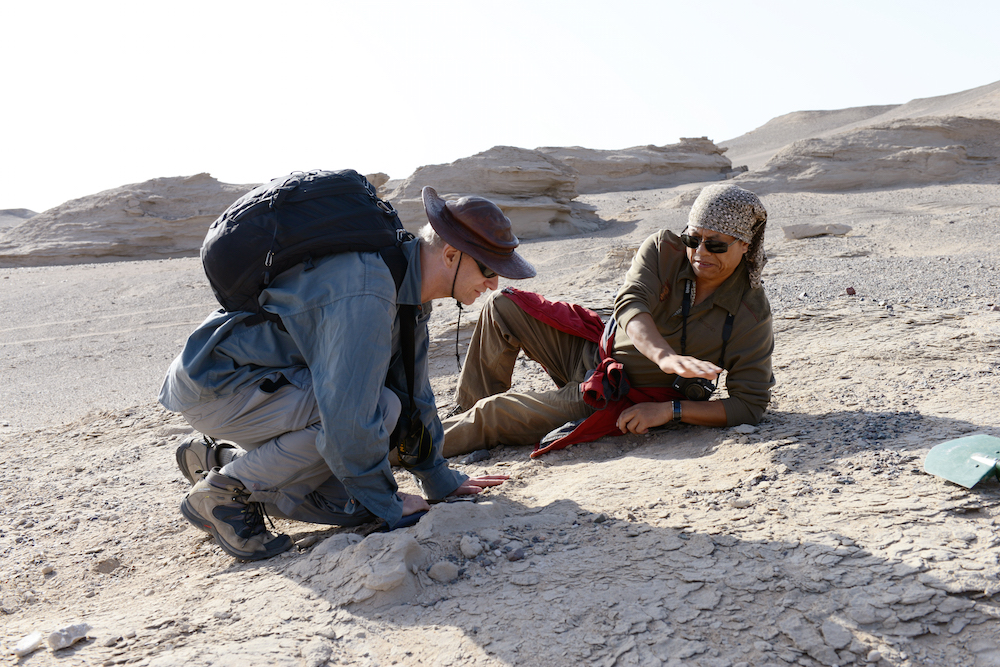

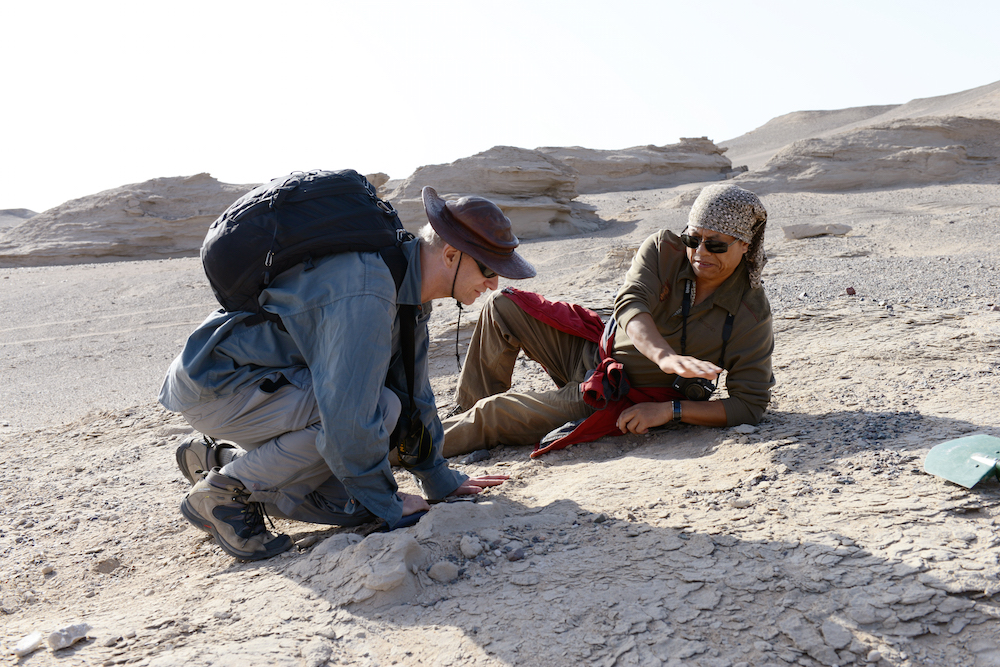

Field work

Paleontologists Xiaolin Wang and Alexander Kellner in the field, collecting new pterosaur specimens.

Pterosaur egg

A pterosaur egg at the site in China.

Note the fragility of this material. Because the egg was soft like parchment, it likely needed to be buried in moist material so that it wouldn't dry out, which would kill the embryo

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another egg

A detail of the pterosaur bone bed shows the pterosaur eggs and bones. There are at least 215 pterosaur eggs at the site that date to the Early Cretaceous.

Ground dwellers

An analysis of 16 baby pterosaur embryos found in northwestern China shows that these little reptiles likely couldn't fly once they hatched. That is, they could probably walk after breaking through their eggs, but couldn't immediately take to the skies.

The discovery comes from a site with 215 pterosaur eggs and the fossilized remains of older pterosaurs. The finding suggests that this species of pterosaur, known as Hamipterus tianshanensis, had colonial nesting behavior. [Read more about the pterosaur egg discovery]

Egg-cellent eggs

Preserved, 120-million-year-old pterosaur eggs.

[Read more about the pterosaur egg discovery]

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus