'Tiny bug slayer' relative of dinosaurs and pterosaurs would have fit in the palm of your hand

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

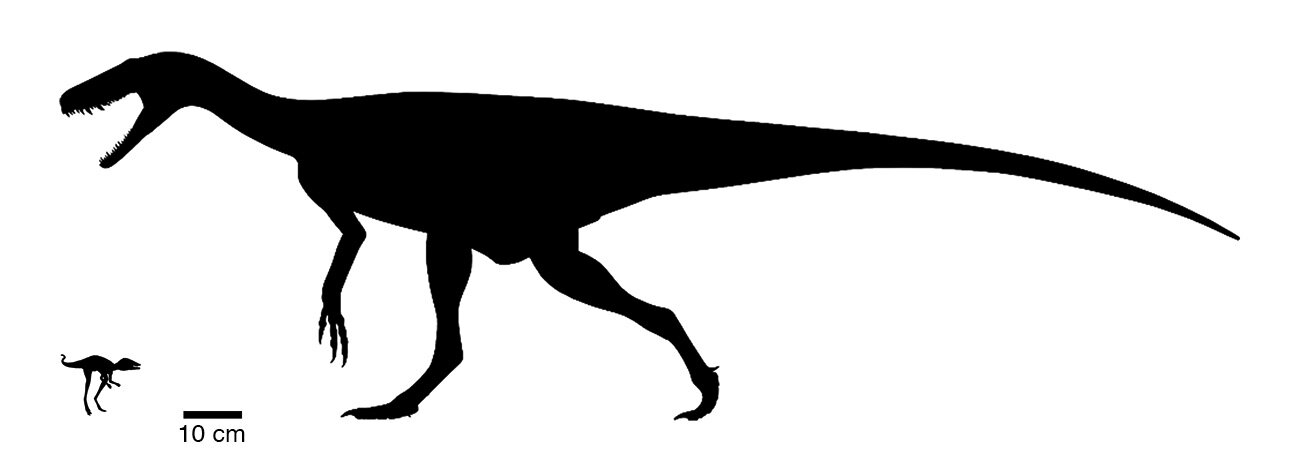

Massive dinosaurs and pterosaurs have a newfound cousin: a palm-size pipsqueak of a reptile, a new fossil reveals.

Even the name of the newly described reptile — Kongonaphon kely, or "tiny bug slayer" in Malagasy and Greek — is an homage to its diminutive size, as well as its likely diet of hard-shelled insects, the researchers said.

This tiny beast reveals that the dinosaurs and pterosaurs — which reached the sizes of school buses and airplanes, respectively — originated from teensy creatures, the researchers wrote in the study.

Related: Photos: School-bus-size dinosaur discovered in Egypt

"There's a general perception of dinosaurs as being giants," study lead researcher Christian Kammerer, a research curator of paleontology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, said in a statement. "But this new animal is very close to the divergence of dinosaurs and pterosaurs, and it's shockingly small."

K. kely, a resident of Madagascar about 237 million years ago during the Triassic period, measured just 4 inches (10 centimeters) tall. Its anatomy may help to explain how pterosaurs achieved flight and why both dinosaurs and pterosaurs had a feather-like fuzz covering their skin, the team noted. (As a reminder, pterosaurs are reptiles that lived at the same time as dinosaurs, but they are not actually dinosaurs.)

The pipsqueak's fossils were discovered in the Morondava Basin of southwestern Madagascar in 1998 by a group of researchers, led by study co-researcher John Flynn, the Frick Curator of Fossil Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City (at the time Flynn worked at the Field Museum in Chicago). An analysis of its anatomy revealed that K. kely belongs to the scientific clade called Ornithodira, whose members are the last common ancestors of the dinosaurs and pterosaurs and their descendants.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The early Ornithodira, however, are poorly known, because there are few known specimens like K. kely that date to the beginning of this lineage.

"It took some time before we could focus on these bones, but once we did, it was clear we had something unique and worth a closer look," Flynn said.

K. kely is one of the smallest non-avian ornithodirans on record. Other known early Ornithodira specimens are also small, but previously these critters were thought to be "isolated exceptions to the rule," Kammerer said.

Miniaturization and "fuzzies"

The discovery of K. kely sheds light on the early evolution of the ornithodirans, Kammerer said, adding that body size decreased sharply early in the history of the dinosaur-pterosaur lineage.

Kammerer added that this "miniaturization" event likely had its advantages, at least when it came to catching prey. For example, the tiny pitted dents on K. kely's closely-packed, conical teeth suggest that it ate insects. In effect, K. kely likely moved into areas that accommodated its small frame and insect cravings, which were likely different than the areas frequented by its mostly carnivorous contemporaries.

In addition, this miniaturization was likely a necessary precursor for the development of flight in vertebrates. "The origin of pterosaurs, the first vertebrates capable of powered flight, is likely related to their ancestry among already-small-bodied early ornithodirans," the researchers wrote in the study.

Related: Gallery: Massive new dinosaur discovered in Sub-Saharan Africa

While K. kely's fossilized bones didn't have any evidence of feather-like fuzzies on them (which is no surprise, because feathers don't fossilize well), other Ornithodira fossils, including those of dinosaurs and pterosaurs, do preserve fossilized feathers. It's likely that the Ornithodira developed fuzzies — ranging from simple filaments to feathers — to keep their owners warm, the researchers said.

That is especially true for little beasties like K. kely, because heat retention in small bodies is challenging. What's more, the mid-late Triassic was a period of temperature extremes, with sudden shifts from hot days to cold nights, so K. kely would have needed all the thermoregulation abilities that fuzzy coverings provided, the researchers said.

Other research has suggested that fur evolved for the same reasons in the ancestors of mammals, the researchers of the new study said. So, it makes sense that these fuzzies, the equivalent for "fur" in reptiles, "likely originated as insulation in small-bodied ancestral ornithodirans," the researchers wrote in the study, which was published online July 6 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus