Corgi-size pterosaurs walked in the rain 145 million years ago

There were about 40 footprints, 30 handprints and many raindrops.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

At the end of the Jurassic period, corgi-size pterosaurs were searching for food along an ancient shoreline when they felt the cool pings of a light rain, new fossil track marks reveal.

Researchers found the fossilized track marks of these winged reptiles interspersed with raindrop impressions near Casper, Wyoming, which used to lie along the Sundance Seaway, a large inland sea that ran from what is now British Columbia in Canada to Utah during the late Jurassic.

"I just picture several of these animals running up and down the coastline looking for something to eat and enjoying a rainy day," study co-researcher Melissa Connely, the Klaenhammer Earth Science Chair at Casper College, told Live Science.

Related: Photos of pterosaurs: Flight in the age of dinosaurs

The research on the pterosaur trackways, which is not yet published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented online Oct. 15 at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology's annual conference; the conference was virtual this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

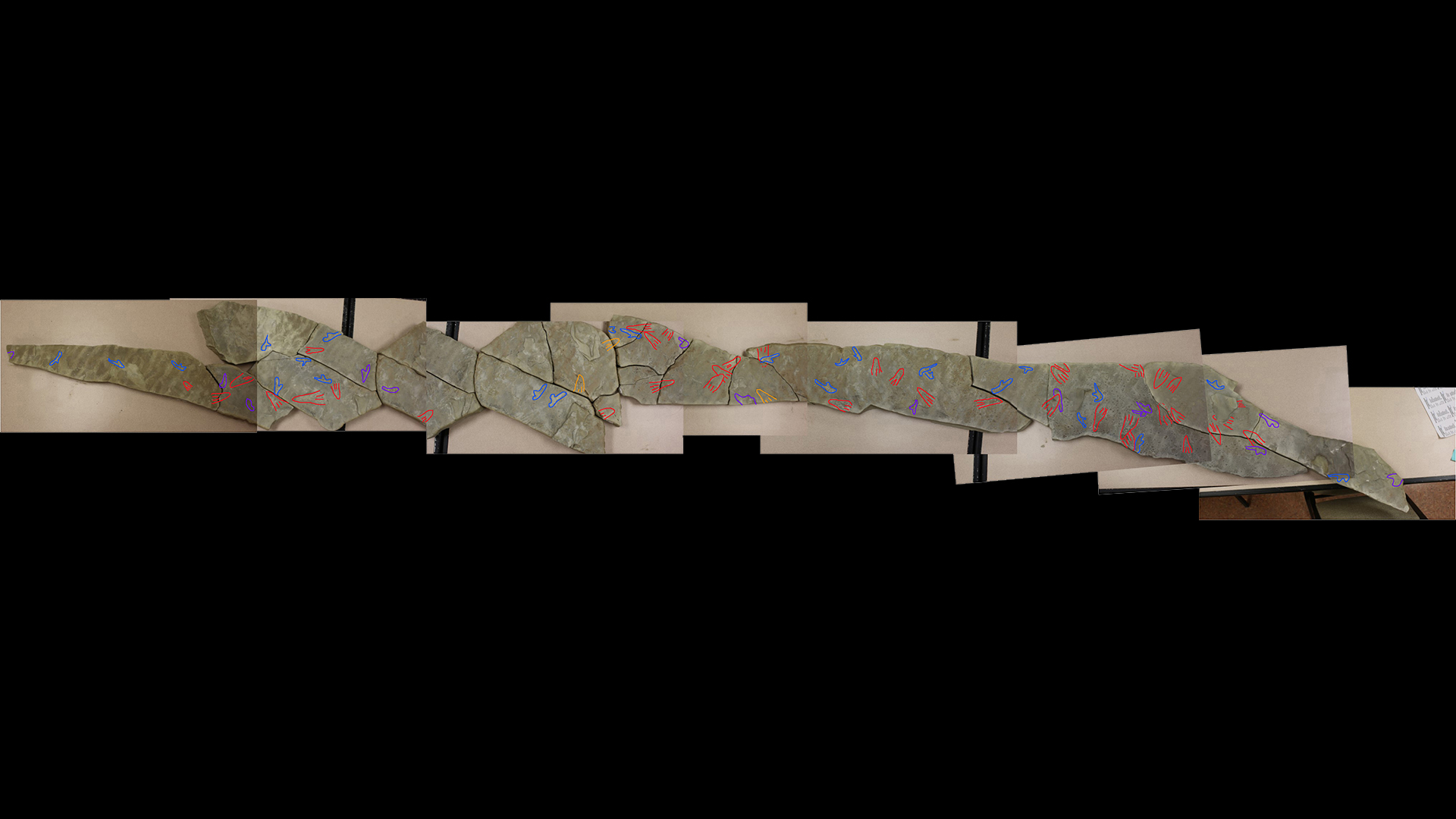

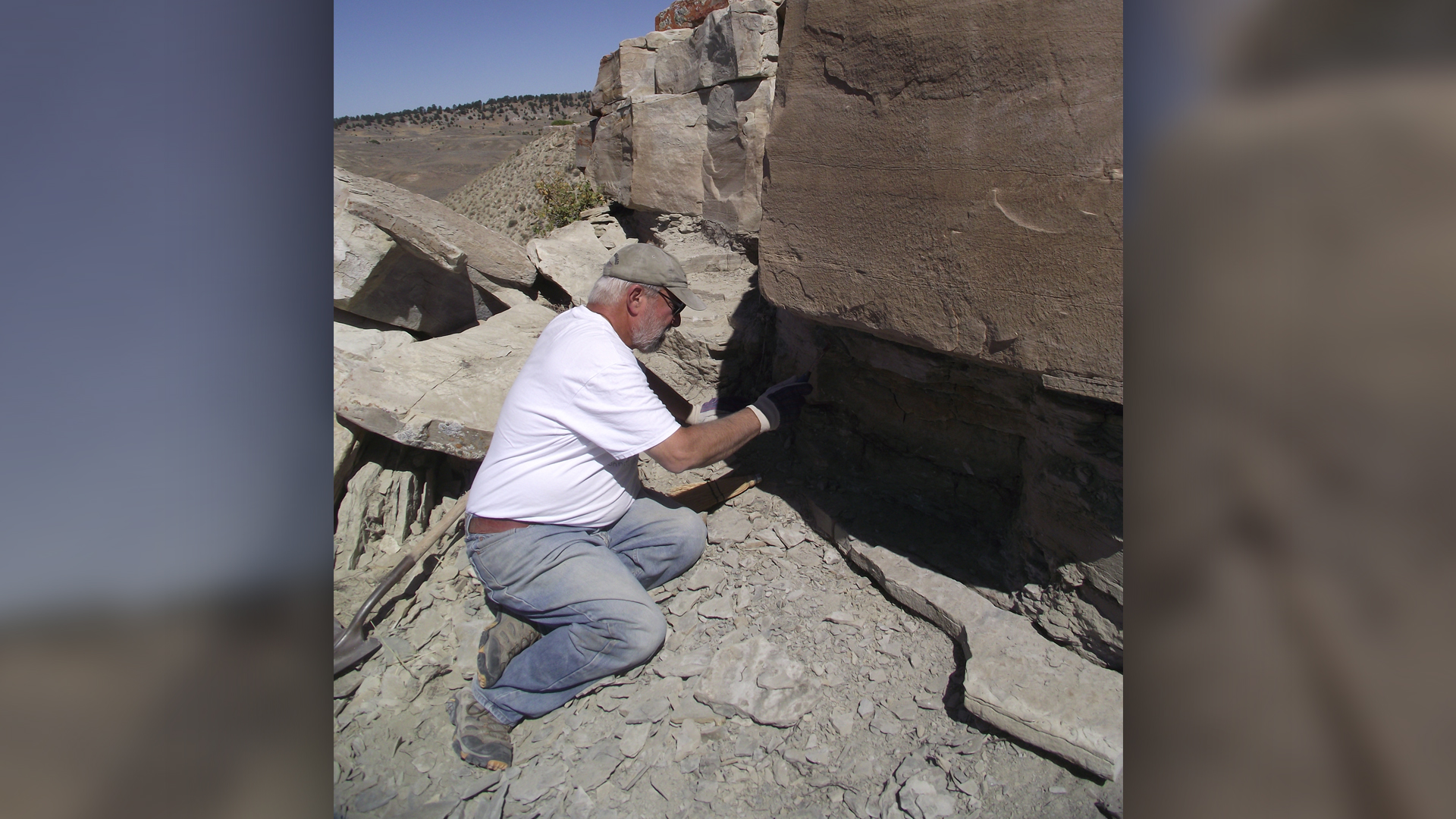

Study co-researcher J.P. Cavigelli, collections manager at Tate Geological Museum at Casper College, found the 145 million-year-old trackway at a private ranch near Casper, in the Sundance Formation in 2016. The tracks were hidden at the base of a massive cliff, making it challenging to reach. So, Cavigelli returned in 2019 with museum volunteers, who helped excavate the slab — 13 feet by 20 inches (4 meters by 50 centimeters) — a prehistoric masterpiece with about 40 pterosaur footprints and 30 handprints that looked like a colorless Jackson Pollock painting.

There are so many prints and they're so jumbled, "there's actually no single trackway that we can follow where one individual walked," Cavigelli told Live Science. "It's a fairly random distribution of handprints and footprints" from many pterosaurs, he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

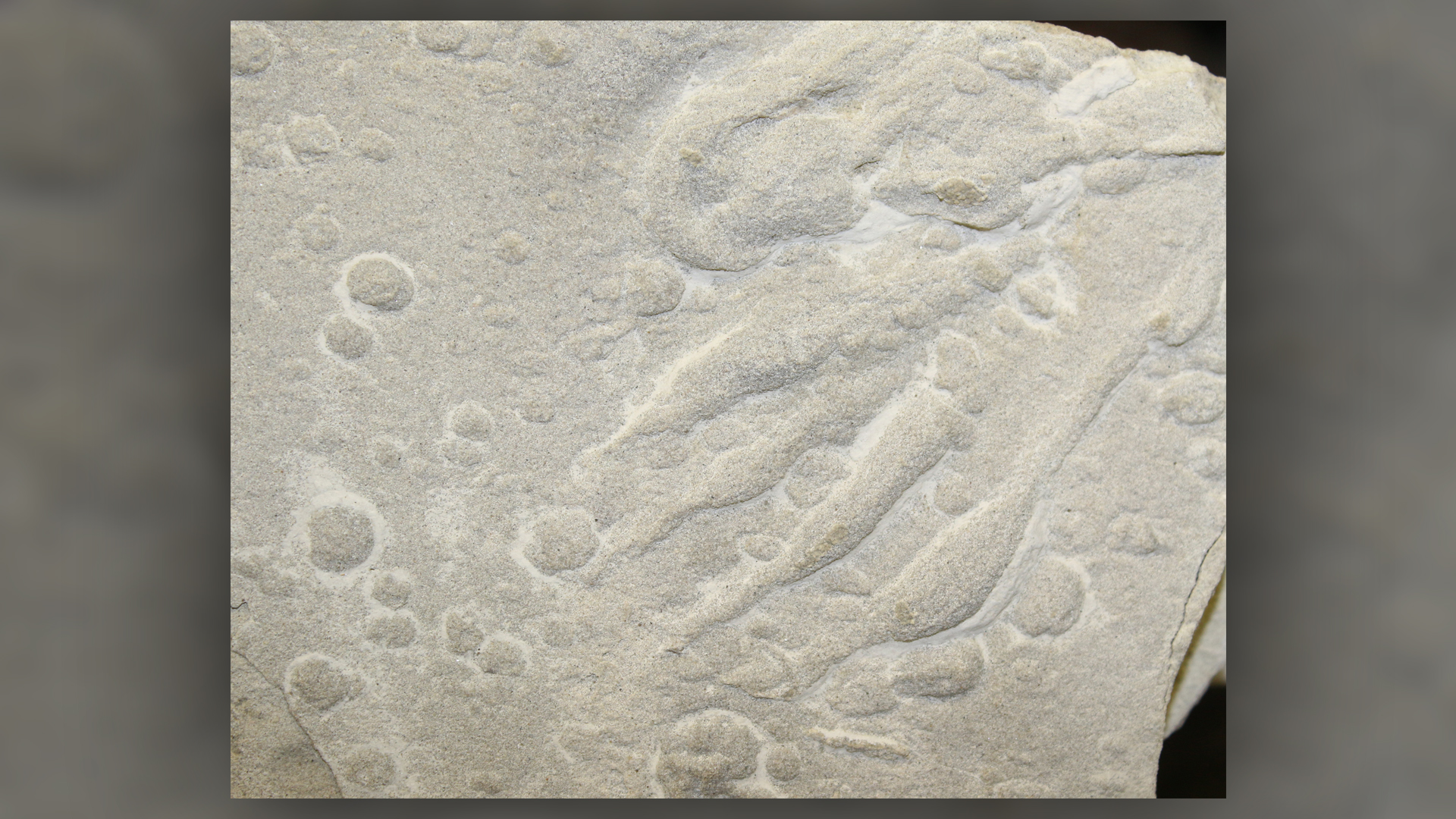

When Connely and Cavigelli examined the slab back at the lab, they saw that it held fossilized ripple marks from the seaway and fossilized raindrop impressions. "That's been on my bucket list, to find a rock with raindrop impressions on it, being a geologist," Connely said. "And to see them on pterodactyl [a type of pterosaur] footprints was just a birthday cake with all the icing."

The tracks are fairly uniform in size, with the footprints measuring about 2.5 inches (6.5 cm) wide and the handprints about 2.1 inches (5.5 cm) across. An analysis revealed that tracks belong to the ichnospecies Pteraichnus (like fossilized bones, trace fossils such as trackways, burrows and poop are given scientific names).

Pteraichnus tracks are found all over the world, including in Morocco, Utah and Wyoming. Just like previously identified Pteraichnus tracks, the newfound prints have a four-toed footprint and shorter "double comma" shaped wrist impressions, the researchers said.

Not much is known about the actual pterosaurs that left these prints, but they were likely the size of a small dog, like a corgi (but not as fat), Connely said. And, judging from their footprints and handprints, "the pterosaurs were walking along the beach, possibly they're coming in and out of the water or maybe looking for something along the shoreline that they could pick up and eat, like most shorebirds do these days," Connely said. (Of note, pterosaurs are flying reptiles, not dinosaurs.)

It's unknown what these pterosaurs ate (researchers have yet to find a skull belonging to this particular species), it's a safe bet to say these flying reptiles chowed down on "everything from small invertebrates to fish," she noted.

Related: Photos: Baby pterosaurs couldn't fly as hatchlings

Connely added that some of the track marks were made on top of raindrops, while others have raindrops in them, suggesting that the pterosaurs "were walking around before and after the rain," she said. The rain is an important detail, because before scientists had established that pterosaurs used all four limbs to walk (making them quadrupeds), some researchers wondered whether pterosaur track marks were made by crocodilians swimming in the water. However, this new finding "nails the lid to the coffin" on that interpretation, because the raindrop impressions clearly show that these track marks were made above water, and therefore couldn't have been made underwater by swimming crocs, Cavigelli said. In addition, paleontologists now know that crocodilian prints look nothing like pterosaur tracks, so it's unlikely crocodilians made these prints above the water.

"The context of the fossil — in this case the raindrop impressions — can in some cases be just as, or even more, informative than the fossil itself," Rachel Belben, a doctoral student of geology at the University of Leicester in England, who wasn't involved in the research but who saw the presentation at the conference, told Live Science.

Ancient trackways are also useful to paleontologists because they "preserve behavior," Connely said. For instance, in the 2001 movie "Jurassic Park III," a giant pterosaur lands on a bridge and begins walking menacingly on all fours toward the protagonists. "It's walking on all fours because of the tracks in Wyoming [and elsewhere] and because we can interpret those behaviors — we can put in pop culture, movies or just give more life to them," Connely said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus