Photos: 'Winged monster' rock art in Black Dragon Canyon

Creationists and researchers have long debated how to interpret the rock art adorning Black Dragon Canyon in Utah. The Fremont culture painted the rock art between A.D. 1 and 1100. Many creationists say the art looks like a winged monster, possibly a pterosaur. In contrast, many researchers say it's a collection of several distinct images of people and animals. A new study using cutting-edge techniques confirms that the artwork consists of several separate images, and is not a pterodactyl. [Read the Full Story on the Ancient Rock Art]

Utah treasure

Researchers used cutting-edge techniques to examine ancient rock paintings in Black Dragon Canyon, Utah. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

Monster dragon

After a man named John Simonson drew an outline around the paintings with chalk, he announced that the image looked like "a weird bird." The above drawing is one interpretation of the rock painting in Utah. (Image credit: courtesy of Starstone Publishing Co.)

Beak or person?

A close-up photo of what some people deem to be the head, beak and neck of the pterosaur. In fact, the image is likely a supplicating person with his arms outstretched to the right, and his legs below him, the researchers said. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

DStretch colors

Researchers analyze the rock art using a computer program called DStretch. Notice the chalk marks added in blue. The yellows correspond to calcite. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

DStretch filter

The same photo in DStretch. The Fremont culture people drew the painting with ochre, so the researchers suppressed all of the colors but red. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

Wing or snake?

A close-up photograph of one of the so-called wings of the pterosaur. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

Bright hues

After putting the same photo into DStretch, "it is very clear that the serpentiform on the right has been artificially joined to the other figures by the chalk line, visible here in blue," the researchers wrote in the study. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

Winged monster?

A close-up view of the other "wing." Notice the white chalk lines that were added in the 1940s, and may have been re-chalked since then. Researchers originally used chalk to help visualize the rock art, but the practice is now illegal.

"It's one of the worst things you can do, because it damages the art, it imposes what you think you can see on it, it messes up the chemistry of the rock, probably, and it just doesn't disappear," said co-lead researcher Paul Bahn, a freelance archaeologist. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

Second take

DStretch shows that the image is actually two four-legged animals. The animal on the left may be a sheep, and the animal on the right may be a dog, Bahn told Live Science. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

Rock art gallery

Compiled DStretch images that show the rock art drawings in their entirety. From left to right, notice the two quadrupeds, the tall person, the supplicating person and the snakelike figure. The style of these images matches other Fremont culture rock-art paintings in the region.

For instance, other paintings show bug-eyed people with round heads and elongated bodies who are surrounded by tiny attendants, such as small people and animals, the researchers said. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

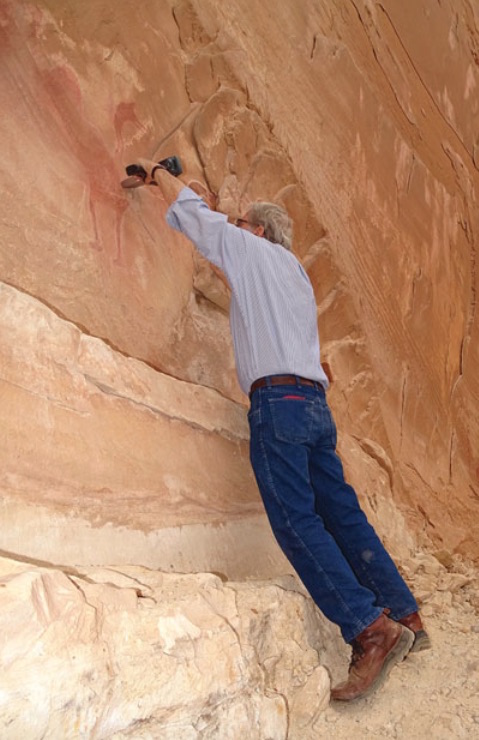

Tippy toes

Researcher Marvin Rowe stands on his tippy toes so he can use a portable mass spectrometer to examine the rock paintings. The spectrometer analyzed the elements found in the painting, and revealed where the paint was and where it wasn't. This confirmed that the rock art is several separate images, and not one big image of a pterosaur, the researchers said. (Image credit: Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, Paul Bahn and Marvin Rowe, "The death of a pterodactyl," Antiquity, Volume 89, p 872-884, 2015, Copyright Antiquity Publications Ltd., published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.)

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.