Bizarre near-Earth asteroid is spinning faster every year — and scientists aren’t sure why

Astronomers have discovered that a potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroid, 3200 Phaethon, has an unusual accelerating spin that could eventually change its trajectory through the solar system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroid is spinning faster and faster every year, and researchers aren't sure why.

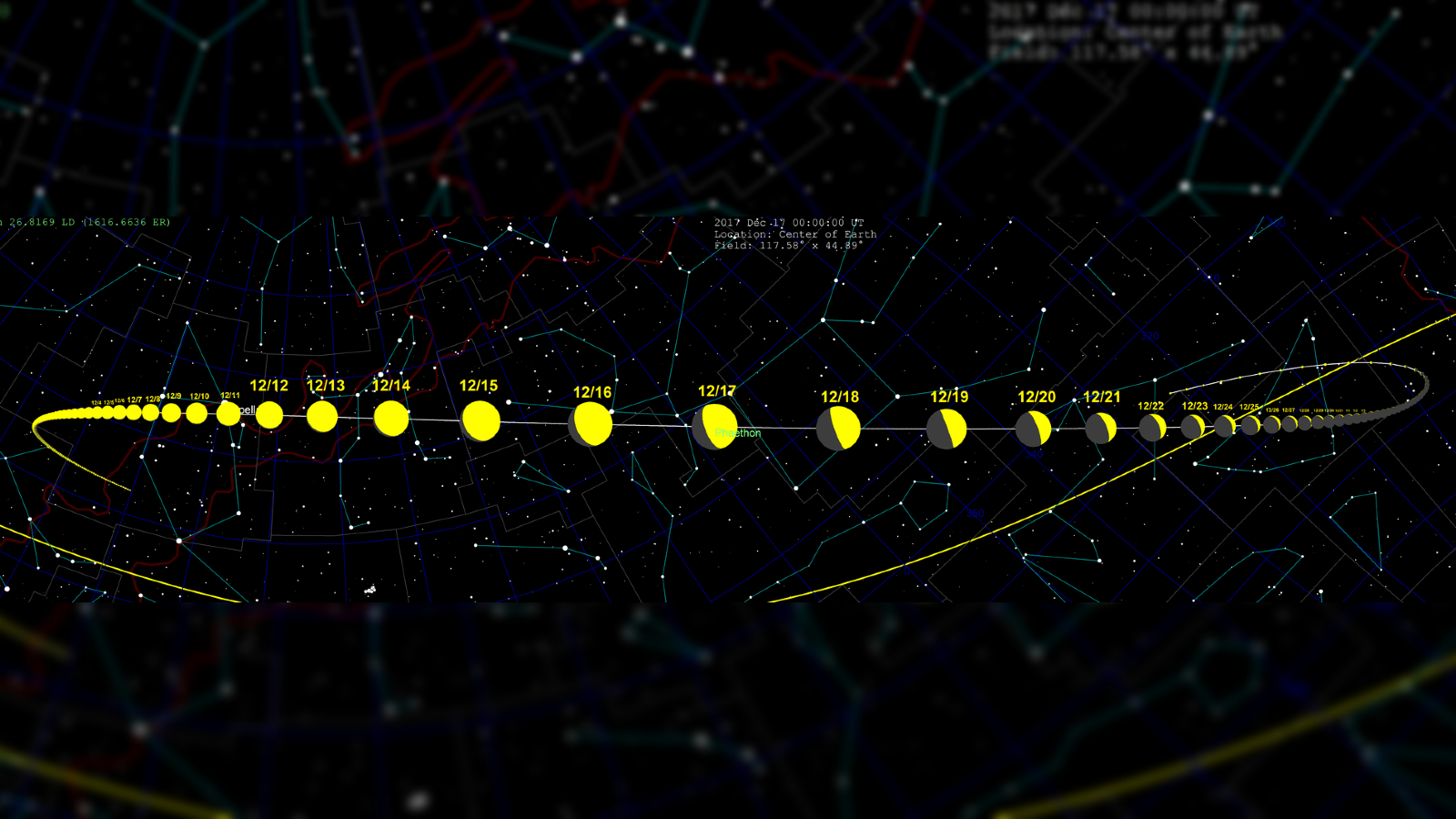

The space rock, known as 3200 Phaethon, is around 3.4 miles (5.4 kilometers) wide, and its orbit through the solar system takes it closer to the sun than any other named asteroid, reaching a minimum distance of around 13 million miles (20.9 million km) from the sun — less than half the distance from Mercury to the sun. During Phaethon's orbit around the sun, which lasts for around 524 days, the space rock travels close enough to Earth to be considered "potentially hazardous." But the closest Phaethon has ever come to our planet was in 2017 when it passed by around 6.4 million miles (10.3 million km) from Earth, or around 27 times farther away than the moon. The asteroid’s dusty trail is responsible for the Geminids meteor shower, which peaks in early December every year and is visible across the globe.

On Oct. 7, a group of researchers presenting at this year's American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences conference revealed that Phaethon has an accelerating spin. The space rock takes around 3.6 hours for one full rotation. But every year, that spin gets around 4 milliseconds shorter, researchers said. This may not sound like much, but over thousands or millions of years the change could alter the asteroid’s orbit, the team added.

Related: Could an asteroid destroy Earth?

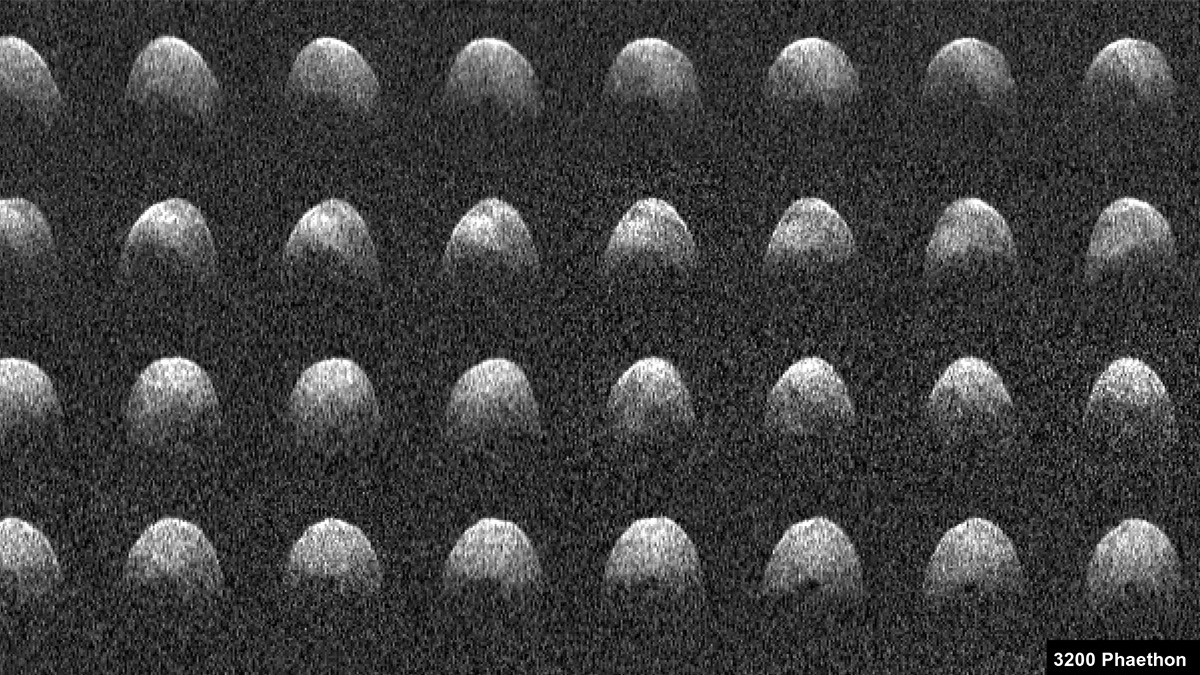

Astronomers first detected Phaethon in 1983 and have been tracking its orbit ever since using light curves — observations of an object's brightness over time that show how it rotates — and radio telescopes, as well as occasional stellar occultations, when the asteroid blocks out the light from a distant star. As a result, Phaethon has one of the most well-known orbital pathways of any asteroid in the solar system, the researchers said in a statement.

Using the decades-old dataset, the new team attempted to simulate the size, shape and rotational properties of Phaethon in greater detail than ever before.

The team found that the near-Earth asteroid is shaped like a spinning top, meaning it is somewhat rounded with a bulge around its equator. This shape is common among large asteroids, such as 162173 Ryugu, which, in 2018, became the first asteroid to be landed on by a spacecraft, when the Japanese space agency (JAXA) mounted the space rock with a probe and successfully snagged precious samples from it.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, when the researchers started analyzing Phaethon's rotation, they found that something didn't add up.

"The predictions from the shape model did not match the data," lead researcher Sean Marshall, an astronomer at the U.S. National Science Foundation's Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, said in the statement. "The times when the model was brightest were clearly out of sync with the times when Phaethon was actually observed to be brightest." After re-analyzing the data, the researchers concluded the only explanation was that Phaethon's spin was increasing year-on-year, Marshall added.

It is very uncommon for an asteroid's spins to change. Phaethon is only the 11th asteroid that has been observed with an accelerating spin, according to the statement. For context, there are more than 1.1 million known asteroids, according to NASA.

Phaethon is also unusual in other ways. First, it has a comet-like tail made up of bits of rubble that break off from its rocky surface. These rocky bits produce the spectacular Geminids meteor shower, which is one of only two known meteor showers that are caused by asteroids and not comets. Second, the sunlight reflected off Phaethon has a blueish hue, which is similar to most comets but almost unheard of among asteroids. As a result, Phaethon is often nicknamed the "rocky comet" by astronomers, according to the statement.

Related: Why are asteroids and comets such weird shapes?

It is unclear exactly why Phaethon's spin is accelerating. The asteroid's comet-like tail means its mass is gradually decreasing, but this does not necessarily mean its spin will change as a result. However, researchers think that the asteroid's unusual tail is the result of its surface getting superheated as it zooms close to the sun. Therefore, the most likely explanation is that the asteroid's surface is getting battered by solar radiation, which is altering its spin — this is known as a Yarkovsky-O'Keefe-Radzievskii-Paddack effect, Science Alert reported. But that theory is hard to prove with the available data.

Due to Phaethon's unusual properties, JAXA has chosen the near-Earth space rock as the target for one of its next asteroid missions. In 2024, the DESTINY+ mission will launch a spacecraft that will eventually fly by Phaethon in 2028, according to the statement.

JAXA's mission scientists will likely find the new discovery of Phaethon's accelerating spin very helpful, researchers said.

"This is good news for the DESTINY+ team," Marshall said. "A steady change means that Phaethon’s orientation at the time of the spacecraft’s flyby can be predicted accurately." For example, scientists will be able to determine which side of the asteroid will be illuminated by the sun when the spacecraft arrives, which will help them to decide which areas to target for their studies, he added.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus