Largest asteroid ever to hit Earth was twice as big as the rock that killed off the dinosaurs

The destructive space rock was somewhere between 12.4 and 15.5 miles wide.

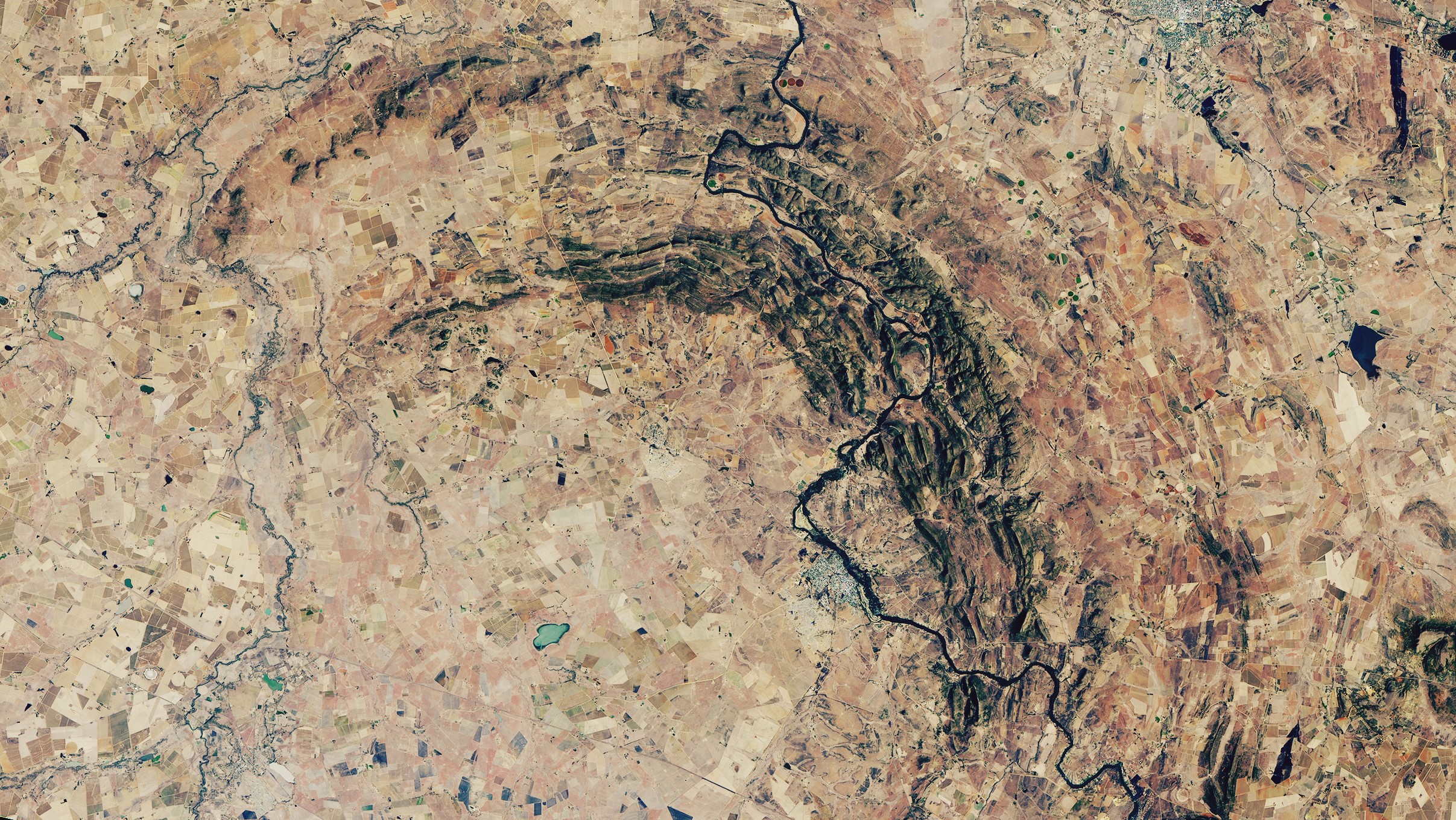

The largest asteroid ever to hit Earth, which slammed into the planet around 2 billion years ago, may have been even more massive than scientists previously thought. Based on the size of the Vredefort crater, the enormous impact scar left by the gargantuan space rock in what is now South Africa, researchers recently estimated that the epic impactor could have been around twice as wide as the asteroid that wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs.

The Vredefort crater, which is located around 75 miles (120 kilometers) southwest of Johannesburg, currently measures about 99 miles (159 km) in diameter, making it the biggest visible crater on Earth. However, it is smaller than the Chicxulub crater buried under Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula, which measures around 112 miles (180 km) in diameter and was left by the dinosaur-killing asteroid that struck Earth at the end of the Cretaceous period about 66 million years ago.

But impact craters slowly erode over time, which makes them shrink. The most recent estimates suggest that the Vredefort crater was originally 155 to 174 miles (250 to 280 km) across when it was formed 2 billion years ago. As a result, the Vredefort crater is considered the largest impact crater on Earth despite being smaller than the Chicxulub crater today.

In the past, scientists thought the Vredefort crater was originally much smaller — around 107 miles (172 km) wide. Based on that estimate, researchers previously calculated that the asteroid responsible for the impact would have measured around 9.3 miles (15 km) across and collided at a speed of around 33,500 mph (53,900 km/h). But in a new study, scientists have revisited the crater's measurements and gained new insight into the size of the enormous space rock.

Related: Could an asteroid destroy Earth?

In the study, which was published online Aug. 8 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, researchers recalculated the size of the Vredefort asteroid and found that the destructive space rock likely measured somewhere between 12.4 and 15.5 miles (20 and 25 km) across, and could have been traveling between 45,000 and 56,000 mph (72,000 and 90,000 km/h) when it struck our planet.

"Understanding the largest impact structure that we have on Earth is critical" because it allows researchers to build more accurate geological models, study lead author Natalie Allen, a doctoral candidate in the Johns Hopkins University Department of Physics and Astronomy in Baltimore, said in a statement. More accurate predictions of impactor sizes also could shed light on other craters on Earth and throughout the solar system, she added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Size uncertainty

In the past, scientists have struggled to pin down the original size of the Vredefort crater due to its erosion over the past 2 billion years.

To understand how erosion affects ancient impact craters such as Vredefort, imagine continually slicing the rim off a bowl, Roger Gibson, a structural geologist at University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa who was not involved in the study, told NASA's Earth Observatory in 2018. "If you slice horizontally through the bowl progressively, you would see that the bowl's diameter will decrease with each slice you take off."

In addition to the natural erosion of the Vredefort impact structure, newer rock formations have emerged atop parts of the crater, the researchers wrote. As a result, most of the crater's original structure has been completely covered by younger rocks and only small sections of the crater's elevated rim are visible today, making it even harder to tell how big the crater used to be.

However, other recent studies have estimated the Vredefort crater's size by focusing on minerals surrounding the crater. By doing this, scientists have spotted deformations and shock fractures in crystals, like quartz and zircon, that were caused by the ancient impact and thereby expand the known radius of the blast, the study authors wrote.

As a result, the researchers are confident that their new estimate for the size of the Vredefort asteroid is more accurate than previous estimates.

A cataclysmic impact

When the dinosaur-killing asteroid, which likely measured around 7.5 miles (12 km) wide, hit Earth around 66 million years ago, the destruction caused by the impact was immense. The Cretaceous-ending event caused widespread forest fires and acid rain; generated mile-high waves in a tsunami that reached halfway across the planet; and sent plumes of ash and dust into the atmosphere, drastically altering the climate. Around 75% of life on Earth was wiped out by the event, according to a study published in December 2021 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Related: World's oldest meteor crater isn't what it seems

Based on the revised calculations of the Vredefort crater's original size, the new study suggests that the Vredefort asteroid was likely around twice as large as the dinosaur-killer. It also may have been traveling much faster, so its impact would have been even more severe — potentially the single largest energy-release event in Earth's history, the study authors reported. However, because the impact happened so long ago, there is scant evidence of the blast's ground-shaking power and the effects of the collision on the planet.

"Unlike the Chicxulub impact, the Vredefort impact did not leave a record of mass extinction or forest fires given that there were only single-cell lifeforms and no trees existed two billion years ago," study co-author Miki Nakajima, a planetary scientist at the University of Rochester in New York, said in the statement. "However, the impact would have affected the global climate potentially more extensively than the Chicxulub impact did."

Therefore, continuing to study Vredefort crater could be the only way researchers learn more about this cataclysmic impact.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus