What are asteroids?

Asteroids are leftovers from the solar system's creation.

Asteroids are flying space rocks occasionally featured in sci-fi movies and perhaps in our low-level fears of going the way of the dinosaurs. But just what are these potato-shaped chunks of rock, and what are the odds that one could hit Earth sometime in the near future?

"You can think about asteroids as planets that didn't make it," Federica Spoto, a research scientist at the Minor Planet Center, an institute that studies small bodies, told Live Science. "They are what's left over from the origin of the solar system."

The solar system coalesced from a cloud of gas and dust about 4.6 billion years ago. Gravity drew the central part of this cloud into a giant ball that ignited into the sun, while the remaining material gradually formed into little pebbles and rocks.

The gravitational attraction between these small objects brought them closer together and allowed some to unify into larger bodies such as planets. Big planets, like Jupiter and Saturn, gobbled up most of the material, Spoto said. "Whoever could grab more got bigger and bigger," she said.

Much of the remaining chunks ended up in the largest asteroids, such as Ceres and Vesta, Spoto added. These were among the first asteroids discovered, with Ceres large enough to be considered a dwarf planet. The scraps became the rest of the asteroids in the solar system.

Where are asteroids found?

Many asteroids can be found in the main asteroid belt, located between Mars and Jupiter. These rocks became confined there by Jupiter's gravitational pull as the giant planet settled into its orbit, Spoto said. The volume of asteroids in the belt was originally much larger, but over billions of years, quirks in Jupiter's gravity occasionally flung an asteroid away, meaning that large numbers of them have been thrown out of the solar system, she added.

More space rocks float around in the Kuiper Belt, which is beyond the orbit of Neptune. In some cases, these objects enter the inner solar system and become heated by the sun. If they get hot enough, material evaporates off the objects and forms a thin atmosphere around them, called a coma. These particular space rocks are typically called comets, Spoto said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: What's the difference between asteroids, comets and meteors?

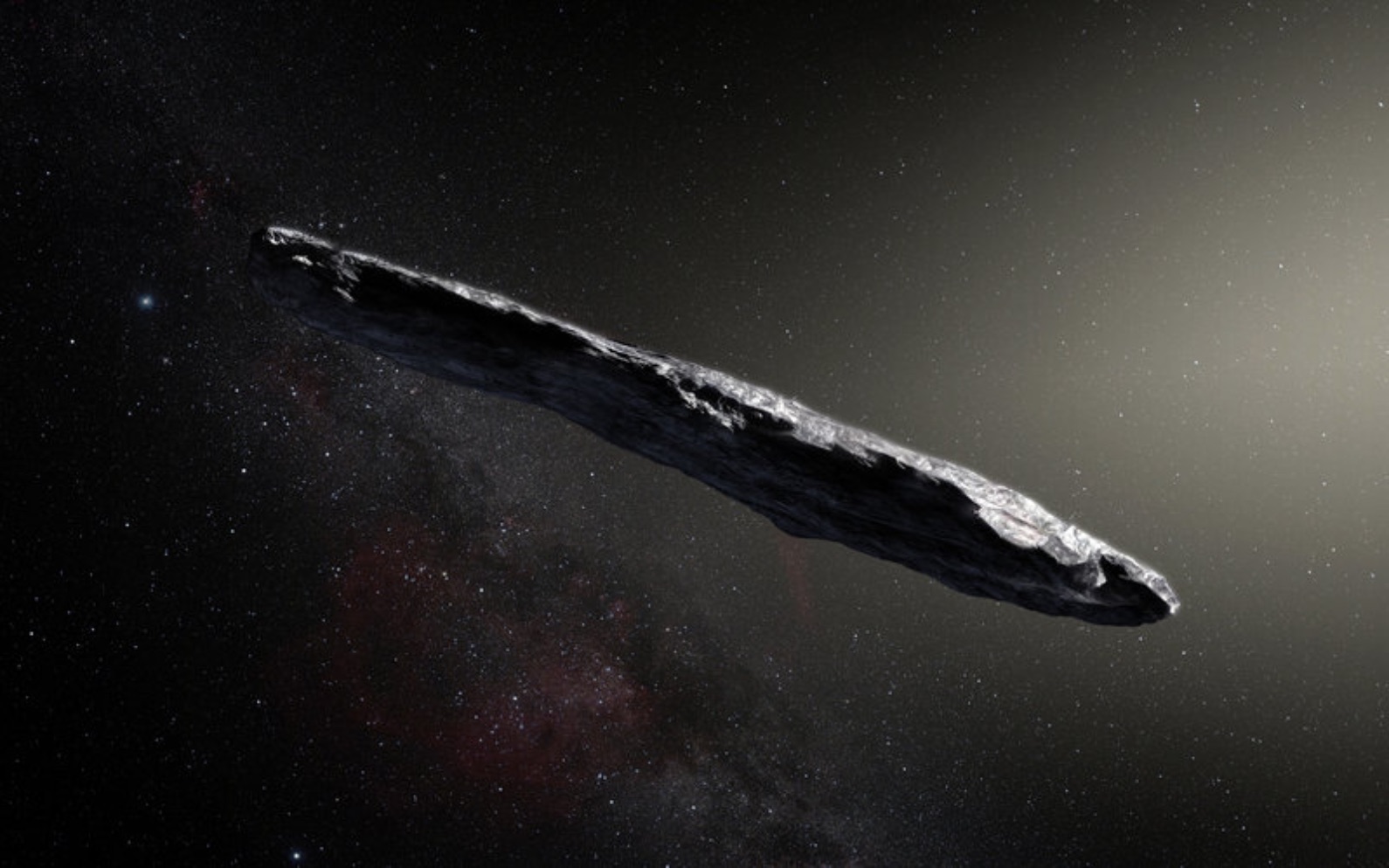

A final group of extremely cold space rocks lives quite far from the sun, in a place known as the Oort cloud. These entities are spread over a distance that stretches nearly halfway to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, Spoto said. Gravitational forces between the solar system and the Proxima Centauri system can occasionally fling the rocks either toward the sun or out into interstellar space. Foreign visitors, such as 'Oumuamua — the first interstellar object ever found in the solar system — were likely slung from their parent star in such a manner.

Main-belt asteroids feel all kinds of forces, such as heat from the sun, as they rotate. If one face of an asteroid becomes warmer than others, it will release infrared radiation that can push the object and set it drifting, bringing it closer to Jupiter or Mars, Spoto said. Gravitational kicks might then send the asteroids "on the highway to Earth," she added, in which case they become what astronomers call near-Earth objects.

Which asteroids will hit us?

As of July 2021, NASA had counted more than 1.1 million known asteroids. Researchers are obviously eager to know if any of these space rocks pose a danger to our planet and have been scanning the skies for hazardous asteroids for a long time.

In 2010, NASA completed a catalog that identified the orbits of 90% of objects 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) in diameter or larger, which would be catastrophic if they hit our planet, and found that none are on collision courses with Earth, according to the agency.

"We've checked for 100 years in the future," Spoto said. "And right now, we don't have any" asteroids that are on track to hit Earth.

NASA currently has a congressional mandate to identify 90% of near-Earth objects that are 460 feet (140 meters) in diameter or larger, which could destroy a city or large region of the countryside if they were to hit our planet. NASA missed its 2020 target to finish such a catalog, but the agency has funding for a space-based telescope mission known as the NEO Surveyor, which should help find a great deal more objects in this size range, Spoto said.

Around 40% to 50% of these medium-size asteroids are estimated to be undiscovered, she added. Instruments such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which will scan the skies constantly each night, will be an additional tool for identifying these potentially hazardous entities, Spoto said.

Smaller space rocks hit Earth almost constantly. But because the majority of our planet is covered in water or thinly populated areas, most of these impacts go unnoticed, Spoto said. Although there have been a few shockers, such as the Chelyabinsk event, in which a meteorite exploded over Russia in 2013, these occurrences are rare.

"People ask us why we didn't know about that one," Spoto said. "It was coming from the direction of the sun during the day, so we couldn't detect it."

Catastrophic impacts — such as the one about 66 million years ago that created a 110-mile-wide (180 km) crater near the town of Chicxulub (pronounced CHEEK'-she-loob), Mexico, and caused a massive extinction of many organisms, including the nonavian dinosaurs — are extremely rare. "We've discovered almost the totality of large objects, like the one that killed the dinosaurs," Spoto said. "We shouldn't have any surprises like that."

Why do scientists study asteroids?

Because asteroids are leftovers from the solar system's earliest days, these rocks can tell researchers a great deal about our origins. "Asteroids didn't experience a lot of transformation during the last 4.6 billion years," Spoto said, so they preserve records of events over that time period.

"We want to know what happened at the beginning," she added. "This is why we have all these missions to grab samples," such as Japan's Hayabusa2 and NASA's OSIRIS-Rex.

Spoto works to understand asteroid families, which came from a single parent body that was hit at some point in the past and exploded into tons of pieces. By studying the fragments, scientists might be able to put together what was going on during various time periods in the solar system's history.

"It's like a puzzle," she said. "You have all these different pieces, and they all tell you something."

Spoto is particularly excited about NASA's upcoming Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), which is expected to launch in November 2021 and reach an asteroid named Didymos in 2026. There, it will test a new type of technology by sending an impactor into Didymos' tiny moon, providing data about how to change the course of any asteroids that might one day threaten our planet.

Additional resources

- Read about NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission, which has collected samples from the asteroid Bennu, from Space.com.

- Watch this animation of all known asteroids and comets in the solar system between 1999 and 2018, from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- Visit the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center for all the latest updates about newly-discovered space rocks

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus