Tsunami from dinosaur-killing asteroid had mile-high waves and reached halfway across the world

One wave was 2.8 miles high.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The dinosaur-killing asteroid that slammed into Earth 66 million years ago also triggered a jumbo-size tsunami with mile-high waves in the Gulf of Mexico whose waters traveled halfway around the world, a new study finds.

Researchers discovered evidence of this monumental tsunami after analyzing cores from more than 100 sites worldwide and creating digital models of the monstrous waves after the asteroid's impact in Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula.

"This tsunami was strong enough to disturb and erode sediments in ocean basins halfway around the globe," study lead author Molly Range, who conducted the modeling study for a master's thesis in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Michigan, said in a statement.

The research on the mile-high tsunami, which was previously presented at the 2019 American Geophysical Union's annual meeting, was published online Tuesday (Oct. 4) in the journal AGU Advances.

Related: Could an asteroid destroy Earth?

Range dove into the tsunami's journey immediately following the asteroid's collision. Based on earlier findings, her team modeled an asteroid that measured 8.7 miles (14 kilometers) across and was zooming 27,000 mph (43,500 km/h), or 35 times the speed of sound when it struck Earth. After the asteroid hit, many lifeforms died; the nonavian dinosaurs went extinct (only birds, which are living dinosaurs, survive today) and about three-quarters of all plants and animal species were wiped out.

Researchers are aware of many of the asteroid's pernicious effects, such as sparking raging fires that cooked animals alive and pulverizing sulfur-rich rocks that led to lethal acid rain and extended global cooling. To learn more about the resulting tsunami, Range and her colleagues analyzed the Earth's geology, successfully analyzing 120 "boundary sections," or marine sediments laid down just before or after the mass extinction event, which marked the end of the Cretaceous period.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These boundary sections matched the predictions of their model of wave height and travel, Range said.

The initial energy from the impact tsunami was up to 30,000 times larger than the energy released by the December 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake tsunami that killed more than 230,000 people, the researchers found.

Once the asteroid struck Earth, it created a 62-mile-wide (100 km) crater and kicked up a dense cloud of dust and soot into the atmosphere. Just 2.5 minutes after the strike, a curtain of ejected material pushed a wall of water outward, briefly making a 2.8-mile-tall (4.5 km) wave that crashed down as the ejecta plummeted back to Earth, according to the simulation.

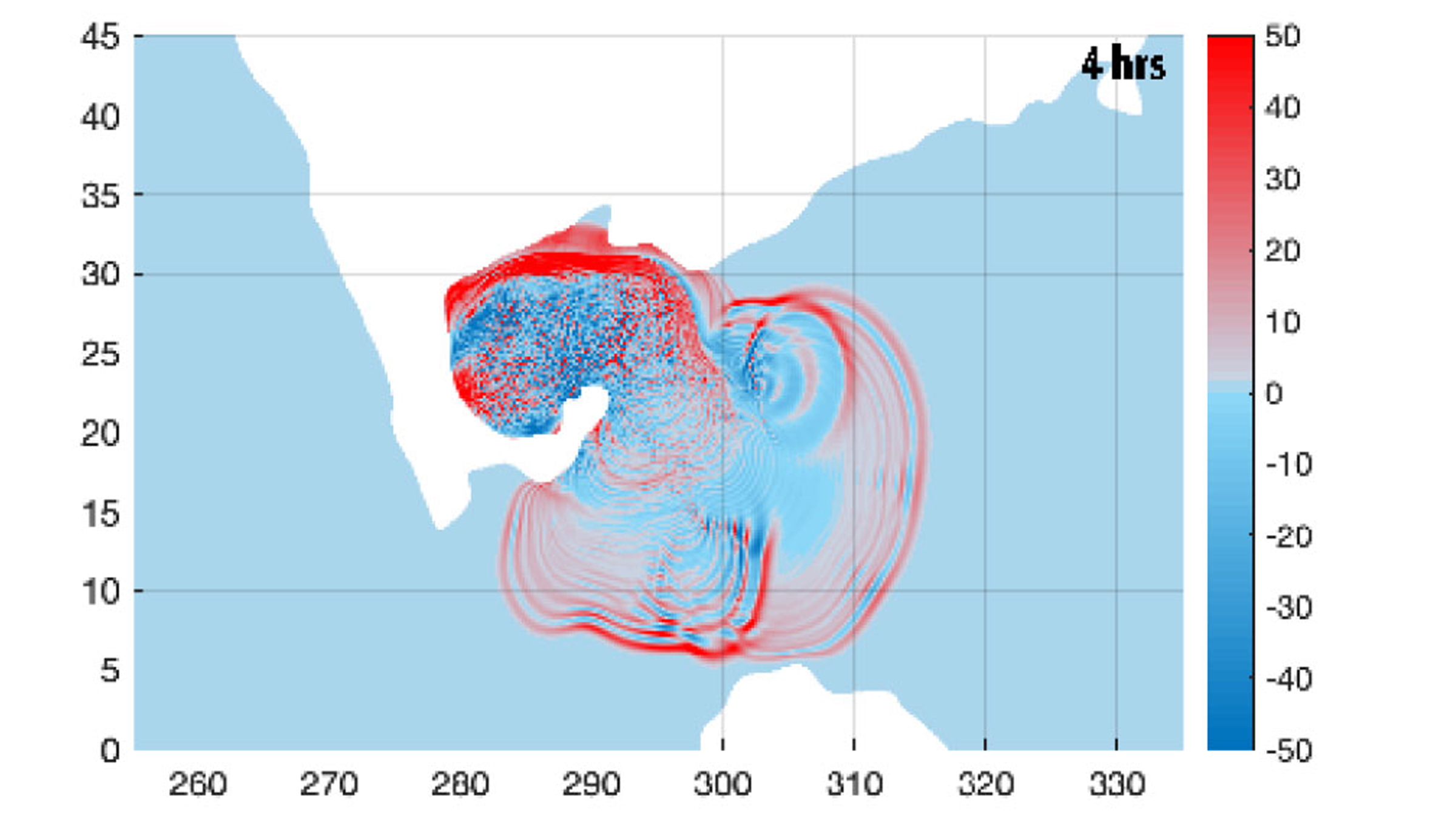

At the 10 minute mark, a 0.93-mile-high (1.5 km) tsunami wave about 137 miles (220 km) away from the impact site swept through the gulf in all directions. An hour after the impact, the tsunami had left the Gulf of Mexico and rushed into the North Atlantic. Four hours following the impact, the tsunami passed through the Central American Seaway — a passage that separated North from South America at the time — and into the Pacific.

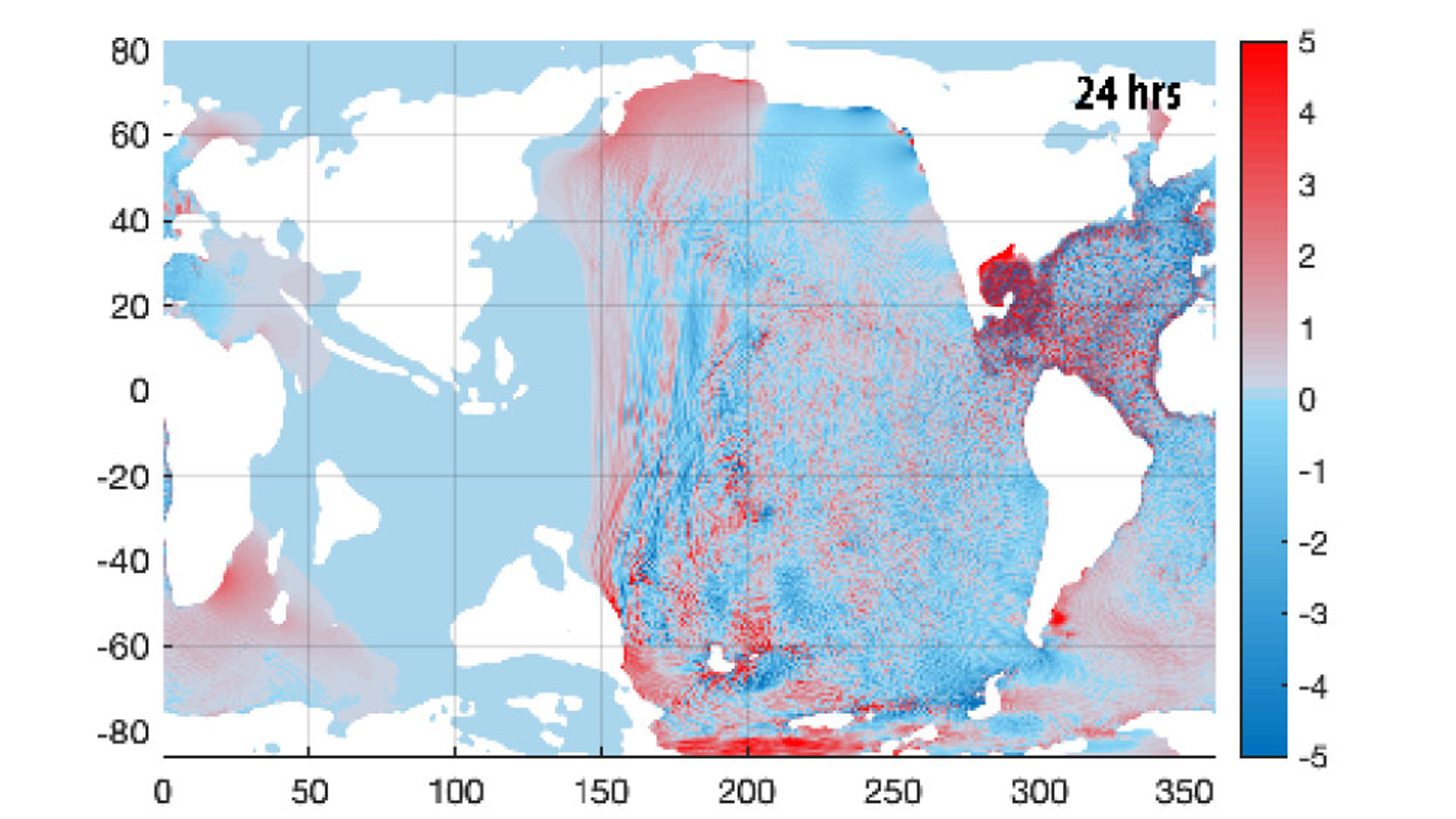

A full day after the asteroid's collision, the waves had traveled through most of the Pacific and the Atlantic, entering the Indian Ocean from both sides, and touching most of the globe's coastlines 48 hours after the strike.

Related: 52-foot-tall 'megaripples' from dinosaur-killing asteroid are hiding under Louisiana

Tsunami's power

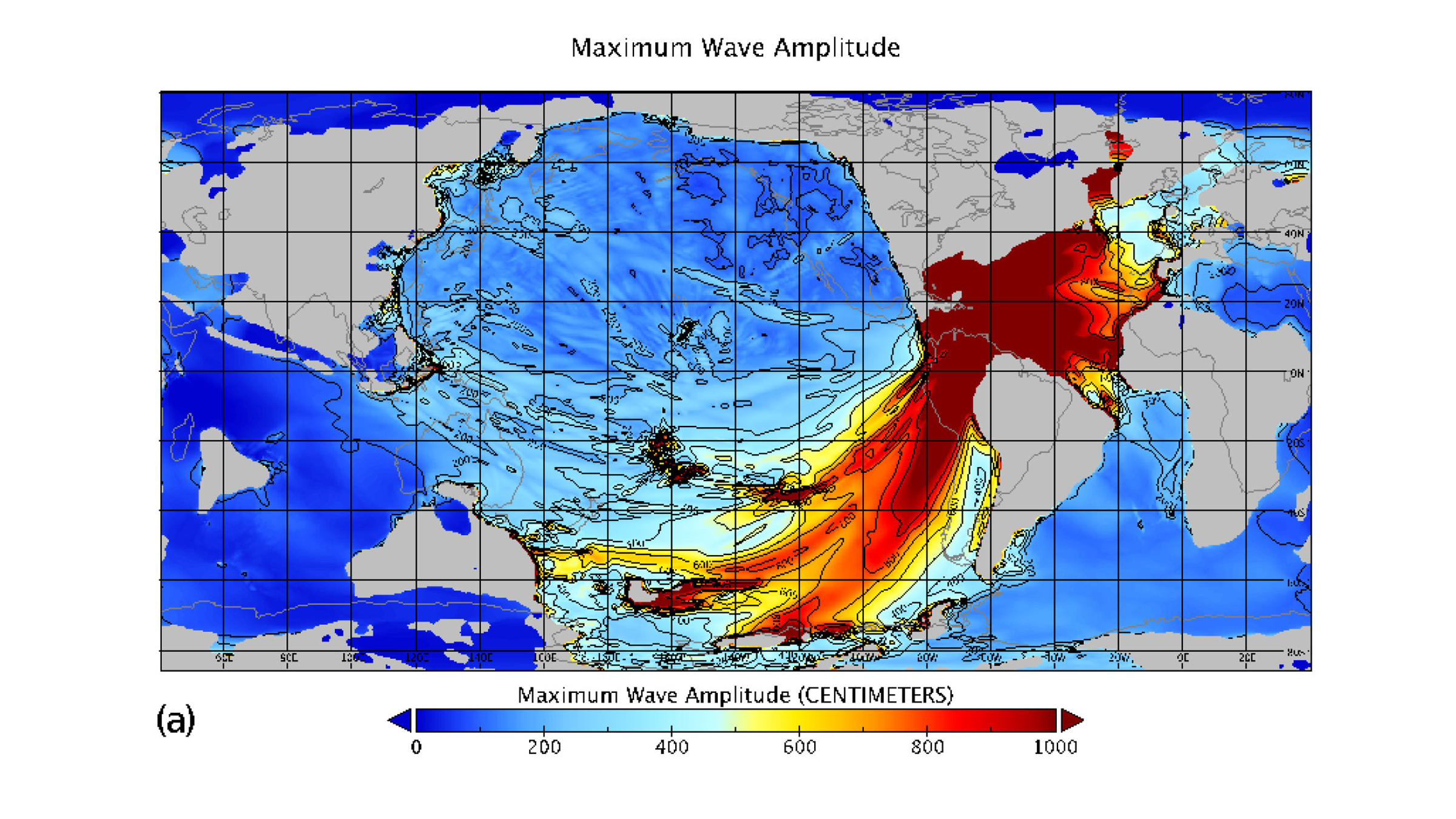

After the impact, the tsunami radiated mostly to the east and northeast, gushing into the North Atlantic Ocean, as well as to the southwest via the Central American Seaway flowing into the South Pacific Ocean. Water traveled so quickly in these areas that it likely exceeded 0.4 mph (0.6 km/h), a velocity that can erode the seafloor's fine-grained sediments.

Other regions largely escaped the tsunami's power, including the South Atlantic, the North Pacific, the Indian Ocean and what is now the Mediterranean sea, according to the team's models. Their simulations showed that the water speeds in these areas were less than the 0.4 mph threshold.

The team even found outcrops — or exposed rocky deposits — from the impact event on eastern New Zealand's north and south islands, a distance of more than 7,500 miles (12,000 km) from the Chicxulub crater in Mexico. Originally, scientists thought that these outcrops were from local tectonic activity. But due to their age and location in the tsunami's modeled route, the study's researchers pinned it to the asteroid's massive waves.

"We feel these deposits are recording the effects of the impact tsunami, and this is perhaps the most telling confirmation of the global significance of this event," Range said.

While the models didn't assess coastal flooding, they did reveal that open-ocean waves in the Gulf of Mexico would have exceeded 328 feet (100 m), and waves would have reached heights of more than 32.8 feet (10 m) as the tsunami approached the North Atlantic's coastal regions and parts of the South America's Pacific coast, according to the statement.

As the water became shallow near the coast, wave heights would have risen dramatically.

"Depending on the geometries of the coast and the advancing waves, most coastal regions would be inundated and eroded to some extent," the authors wrote in the study. "Any historically documented tsunamis pale in comparison with such global impact."

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus