A Second Interstellar Visitor Has Arrived in Our Solar System. This Time, Astronomers Think They Know Where It Came From

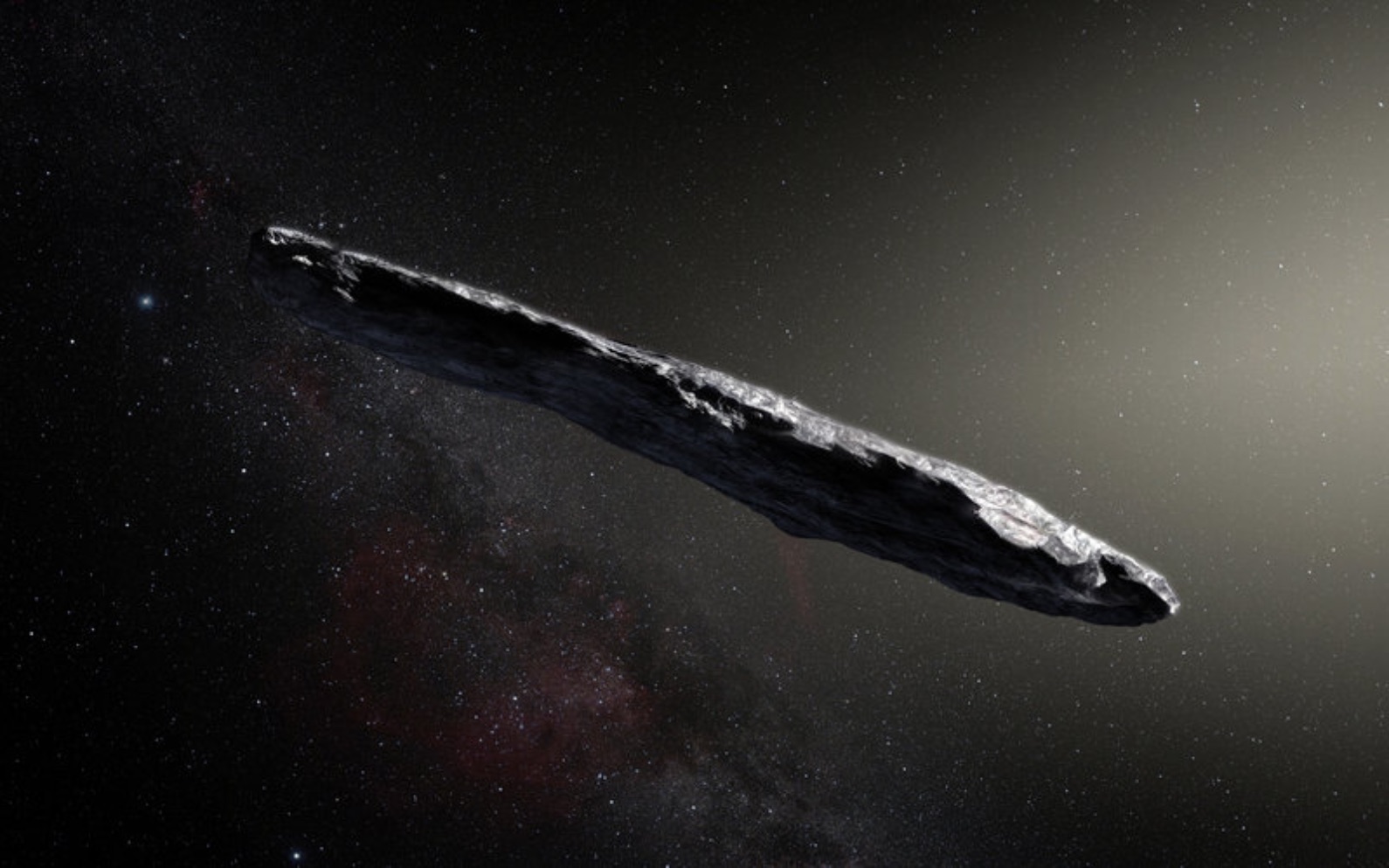

When 'Oumuamua passed through our solar system in 2017, no one could figure out where the object came from. But astronomers think they've worked out how Comet 2I/Borisov got here.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For the second time ever, astronomers have detected an interstellar object plunging through our solar system. But this time, researchers think they know where it came from.

Gennady Borisov, an amateur astronomer working with his own telescope in Crimea, first spotted the interstellar comet on Aug. 30. His find made the object the first interstellar visitor discovered since oblong 'Oumuamua flashed through our solar neighborhood back in 2017. Now, in a new paper, a team of Polish researchers has calculated the path this new comet — known as Comet 2I/Borisov or (in early descriptions) as C/2019 Q4 — took to arrive in our sun's gravity well. And that path leads back to a binary red dwarf star system 13.15 light-years away, known as Kruger 60.

When you rewind Comet Borisov's path through space, you'll find that 1 million years ago, the object passed just 5.7 light-years from the center of Kruger 60, moving just 2.13 miles per second (3.43 kilometers per second), the researchers wrote.

Related: 11 Fascinating Facts About Our Milky Way Galaxy

That's fast in human terms —— about the top speed of an X-43A Scramjet, one of the fastest aircraft ever built. But an X-43A Scramjet can't overcome the sun's gravity to escape our solar system. And the researchers found that if the comet were really moving that slowly at a distance of no more than 6 light-years from Kruger 60, it probably wasn't just passing by. That's probably the star system it came from, they said. At some point in the distant past, Comet Borisov lively orbited those stars the way comets in our system orbit ours.

Ye Quanzhi, an astronomer and comet expert at the University of Maryland who wasn't involved in this paper, told Live Science that the evidence pinning Comet 2I/Borisov to Kruger 60 is pretty convincing based on the data available so far.

"If you have an interstellar comet and you want to know where it came from, then you want to check two things," he said. "First, has this comet had a small pass distance from a planetary system? Because if it's coming from there, then its trajectory must intersect with the location of that system."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though the 5.7 light-years between the new comet and Kruger may seem bigger than a "small gap" — nearly 357,000 times Earth's distance from the sun — it's close enough to count as "small" for these sorts of calculations, he said.

"Second," Ye added, "usually comets are ejected from a planetary system due to gravitational interactions with major planets in that system."

In our solar system, that might look like Jupiter snagging a comet that's falling toward the sun, slingshotting it around in a brief, partial orbit and then flinging it away toward interstellar space.

"This ejection speed has a limit," Ye said. "It can't be infinite because planets have a certain mass," and the mass of a planet determines how hard it can throw a comet into the void. "Jupiter is pretty massive," he added, "but you can't have a planet that's 100 times more massive than Jupiter because then it would be a star."

Related: 15 Amazing Images of Stars

That mass threshold sets an upper limit on the speeds of comets escaping star systems, Ye said. And the authors of this paper showed that Comet 2I/Borisov fell within the minimum speed and distance from Kruger 60 to suggest it originated there —assuming their calculations of its trajectory are correct.

Studying interstellar comets is exciting, Ye said, because it offers a rare opportunity to study distant solar systems using the precise tools scientists employ when examining our own. Astronomers can look at Comet 2I/Borisov using telescopes that might reveal details of the comet's surface. They can figure out whether it behaves like comets in our own system (so far, it has) or does anything unusual, like 'Oumuamua famously did. That's a whole category of research that usually isn't possible with distant solar systems, where small objects only ever appear —— if they're visible at all —— as faint, discolored shadows on their suns.

This research, Ye said, means that anything we learn about Comet Borisov could be a lesson about Kruger 60, a nearby star system where no exoplanets have been discovered. 'Oumuamua, by contrast, seems to have come from the general direction of the bright star Vega, but according to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, researchers don't believe that's where the object originally came from, instead suggesting it likely came from a newly-forming star system (though researchers aren't sure which one).. That would make Comet Borisov the first interstellar object ever traced to its home system, if these results are confirmed.

However, the paper's authors were careful to point out that these results shouldn't yet be considered conclusive. Astronomers are still collecting more data about Comet 2I/Borisov's path through space, and additional data may reveal that the original trajectory was wrong and that the comet came from somewhere else.

The paper tracing the comet's origin has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, but it's available on the preprint server arXiv.

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- Crash! 10 Biggest Impact Craters on Earth

- 9 Strange, Scientific Excuses for Why Humans Haven't Found Aliens Yet

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus