First Martian life likely broke the planet with climate change, made themselves extinct

The microbes could have created a reverse greenhouse effect which made the planet inhospitable

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

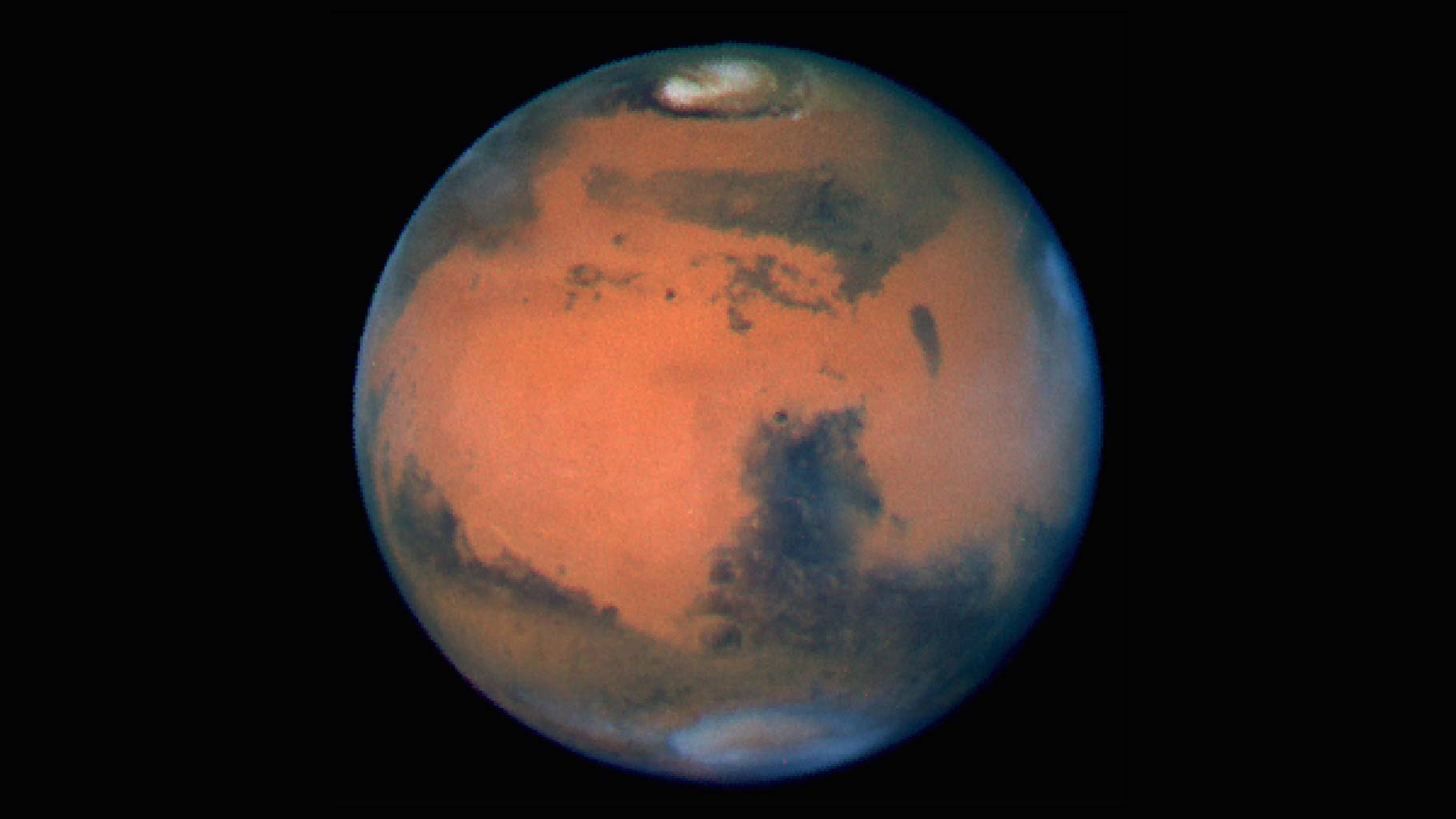

Ancient microbial life on Mars could have destroyed the planet’s atmosphere through climate change, which ultimately led to its extinction, new research has suggested.

The new theory comes from a climate modeling study that simulated hydrogen-consuming, methane-producing microbes living on Mars roughly 3.7 billion years ago. At the time, atmospheric conditions were similar to those that existed on ancient Earth during the same period. But instead of creating an environment that would help them thrive and evolve, as happened on Earth, Martian microbes may have doomed themselves just as they were getting started, according to the study published Oct. 10 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The model suggests that the reason life thrived on Earth and was doomed on Mars is because of the gas compositions of the two planets, and their relative distances from the sun. Being farther away from our star than Earth, Mars was more reliant on a potent fog of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen, to maintain hospitable temperatures for life. So as ancient Martian microbes ate hydrogen (a potent greenhouse gas) and produced methane (a significant greenhouse gas on Earth but less potent than hydrogen) they slowly ate into their planet’s heat-trapping blanket, eventually making Mars so cold that it could no longer evolve complex life.

Related: Curiosity rover discovers that evidence of past life on Mars may have been erased

As Martian surface temperatures dropped from a tolerable range between 68 and 14 degrees (10 to 20 degrees Celcius) Fahrenheit to a punishing minus 70 F (minus 57 C), the microbes fled deeper and deeper into the warmer crust of the planet — burrowing more than 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) deep only a few hundred million years after the cooling event.

To find evidence for their theory, the researchers want to find out if any of these ancient microbes survived. Traces of methane have been detected on Mars’ sparse atmosphere by satellites, as well as in the form of ‘alien burps’ spotted by NASA’s Curiosity rover, which could be evidence that the microbes still exist.

The scientists believe their findings suggest that life may not be innately self-sustaining in every conducive environment it pops up in, and that it can easily wipe itself out by accidentally destroying the foundations for its own existence.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The ingredients of life are everywhere in the universe," study lead author Boris Sauterey, an astrobiologist at the Institut de Biologie de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, France told Space.com. "So it's possible that life appears regularly in the universe. But the inability of life to maintain habitable conditions on the surface of the planet makes it go extinct very fast. Our experiment takes it even a step farther as it shows that even a very primitive biosphere can have a completely self-destructive effect."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus