If 'Oumuamua Is an Alien Spacecraft, It's Keeping Quiet So Far

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

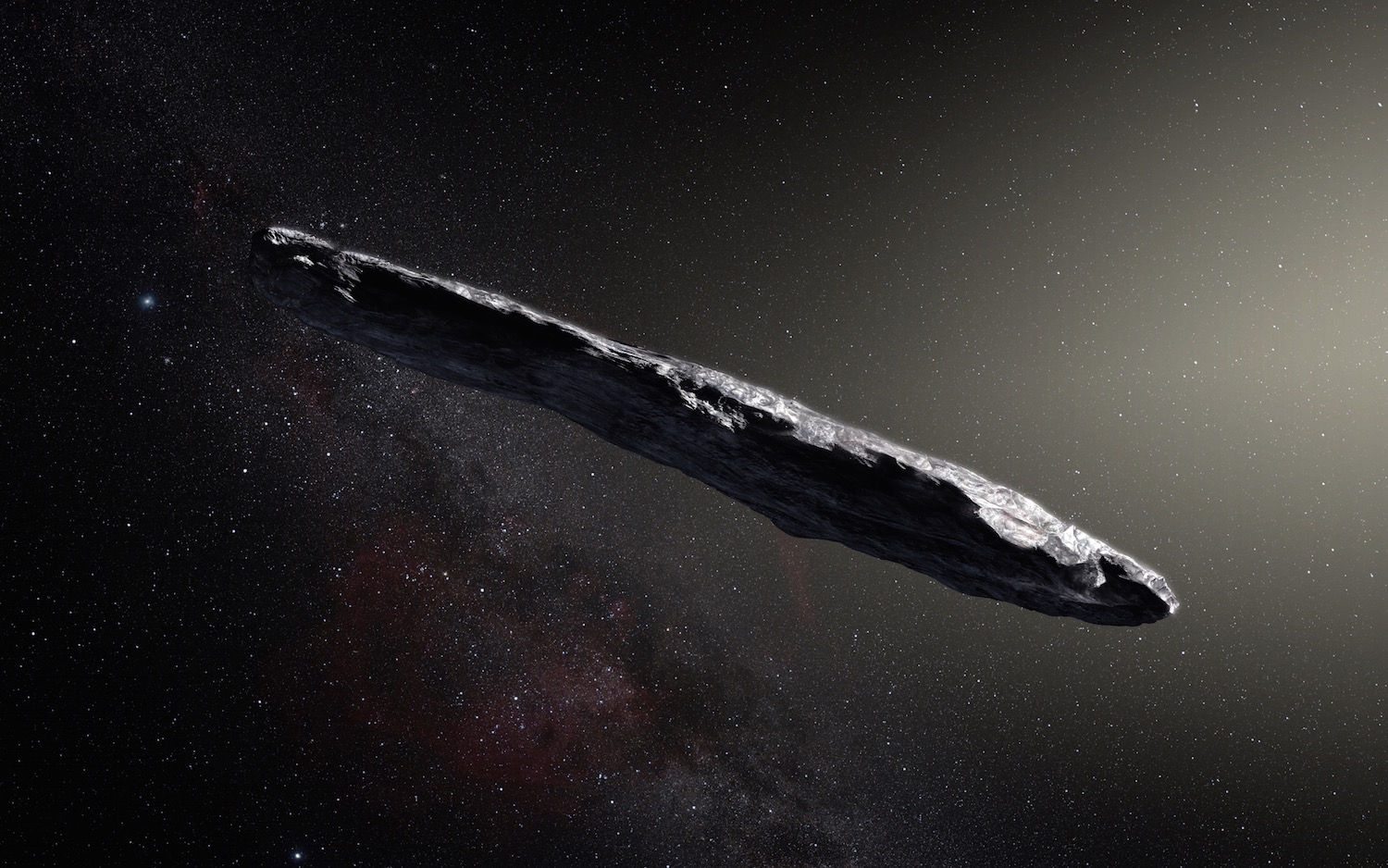

Are there intelligent aliens living on the cigar-shaped, interstellar object that's zooming through our solar system? To find out, astronomers in the outback of Western Australia used the Murchison Widefield Array telescope to eavesdrop on the rocky visitor.

Their finding? No cigar — there was no evidence of little green men sending out signals, according to a new study.

"We found no such signals with non-terrestrial origins," the researchers wrote in the paper. [5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids]

Researchers learned about the mysterious, reddish space rock last year when it was spotted by the Pan-STARRS1 telescope in Hawaii on Oct. 19, 2017, Live Science's sister site Space.com previously reported. Scientists named it 'Oumuamua, Hawaiian for "a messenger from afar arriving first." The name highlights 'Oumuamua's unique background; it's the first direct evidence of an object that originated in another star system and that has passed through our own solar system, Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate at the agency's headquarters in Washington, D.C., said in a statement at the time.

'Oumuamua's peculiar, seemingly cigar-like shape and unusual orbital characteristics prompted some people to wonder whether it was an interstellar spacecraft, the researchers of the new study said. So, they decided to "examine our data for signals that might indicate the presence of intelligent life associated with 'Oumuamua," they wrote in the study.

To investigate, the astronomers turned to the Murchison Widefield Array, a telescope located in Western Australia's remote Murchison region, far away from the buzz of human activity and radio interference. They looked back at data produced by the Murchison Widefield Array during November, December and early January, when 'Oumuamua was between 59 million and 366 million miles (95 million and 590 million kilometers) from Earth.

In particular, the astronomers checked for radio transmissions coming from the roughly quarter-mile-long (400 meters) 'Oumuamua between the frequencies of 72 and 102 megahertz, a range that is similar to the frequencies used in FM radio broadcasts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These transmitter powers are well within the capabilities of human technologies, and are therefore plausible for alien civilizations," the researchers wrote in the study. [Greetings, Earthlings! 8 Ways Aliens Could Contact Us]

The results added more evidence that 'Oumuamua is not a complex alien ship — or if it is, it's not talking on those frequencies. Rather, it's most likely the fragment of a comet that lost much of its surface water after being bombarded by cosmic rays on its lengthy trek through interstellar space, the researchers said.

Even though the team didn't hear any transmissions that might have been produced by intelligent alien life, the research was an important step in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, the astronomers said.

"If advanced civilizations do exist elsewhere in our galaxy, we can speculate that they might develop the capability to launch spacecraft over interstellar distances and that these spacecraft may use radio waves to communicate," study lead researcher Steven Tingay, deputy executive director at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) in Australia, said in a statement.

There could be more than 46 million similar interstellar objects crossing through the solar system every year, research shows. The majority of these objects are too distant for the Murchison Widefield Array to study, but future telescopes, including the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), which is expected to be built in Australia and South Africa, could help astronomers examine these interstellar interlopers, the researchers said.

The study, which is posted on the preprint site ArXiv, has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus