Why is it hard to hear when you have a cold?

Coming down with a cold or the flu can muffle your hearing, but why?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The common cold can leave you with a stuffy nose, sore throat and phlegmy cough, but along with these main symptoms, you may also struggle to hear properly.

So why does your sense of hearing falter when you have a cold or another respiratory infection?

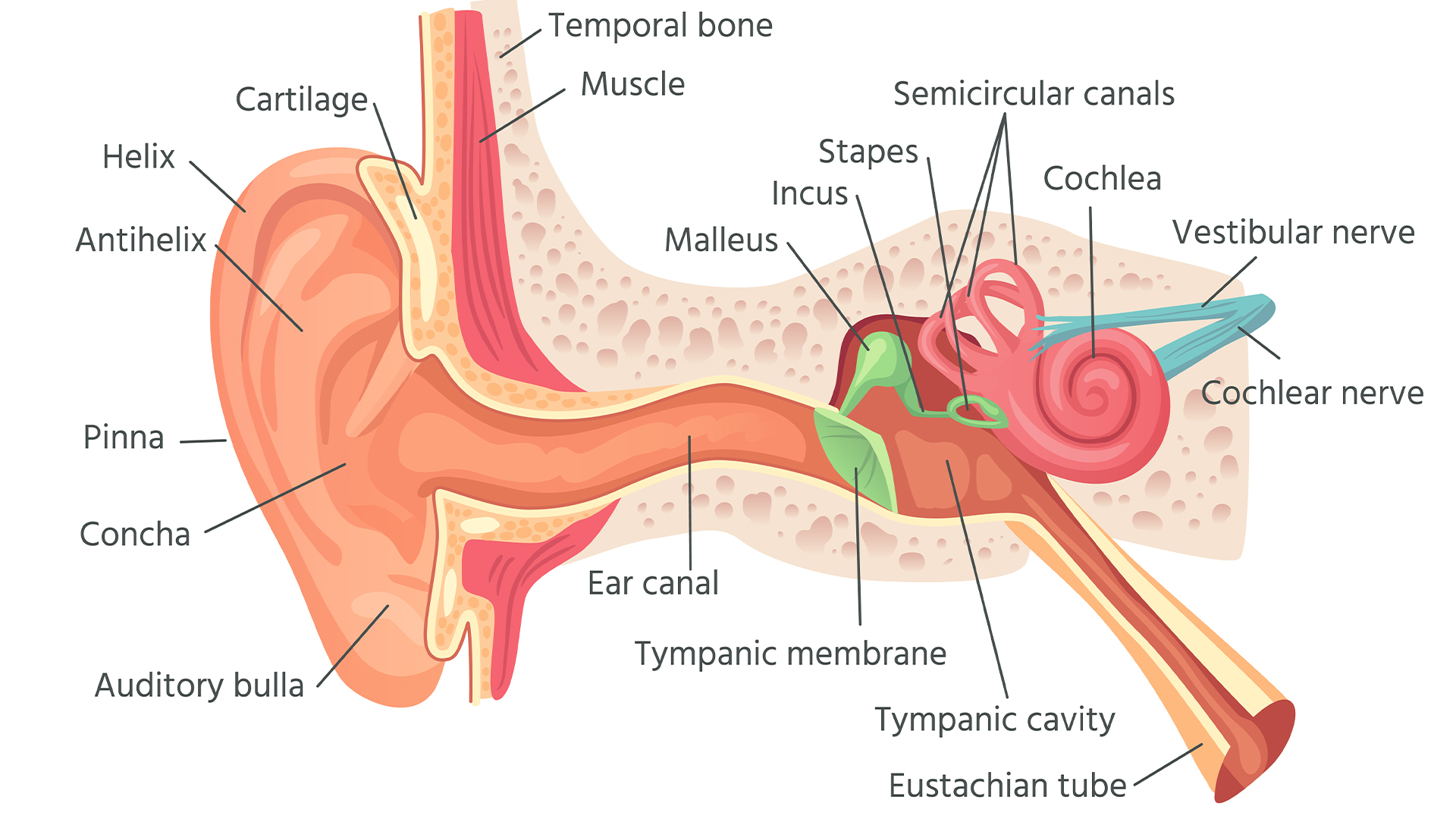

The answer lies in the Eustachian tube, a narrow canal that connects your ear with the back of your nose, Dr. John Fornadley, a Pennsylvania-based ear, nose and throat specialist and a clinical associate professor of surgery at Penn State, told Live Science by email.

The hollow Eustachian tube is typically closed, but it opens when we swallow or yawn, according to Stanford Medicine. It helps to drain excess mucus made by the lining of the middle ear into the nose and throat, and it's also critical to our sense of hearing.

Related: How long do cold symptoms last?

"Our eardrums vibrate in response to sound, and they transmit this vibration to the inner ear," Fornadley said. "To do this effectively, the eardrum, like the musical instrument drum, requires air behind the drum to have the same air pressure as air on the outside of the eardrum for normal vibration." The Eustachian tube connects the space behind the eardrum, known as the middle ear, to the nose in order to equalize the air pressure in the middle ear with that of the outside world, he explained.

When there is a significant difference in air pressure, the Eustachian tube opens rapidly — this is the sensation often referred to as "popping" the ears. And if the tube doesn't pop open on its own, you can force it to by pinching your nose and then blowing air into the ear.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We are more aware of the ears popping when traveling by air, or going up a mountain quickly in a vehicle," Fornadley said. "The process of opening the Eustachian tube remains important, just more subtle, when living at sea level."

When cold or other respiratory viruses infect you, they trigger an immune response. To combat the infection, the nose and sinuses rapidly increase their production of mucus and swell as the tissues become inflamed, creating the sensation of a stuffy nose. This extra fluid can then spread to the ear through the Eustachian tube and blunt the vibration of the eardrum as a result.

Related: How does water get stuck in your ear — and how do you get it out?

"For this reason, nasal congestion will temporarily decrease hearing," Fornadley said.

In addition, the resulting buildup of mucus in the Eustachian tube can sometimes cause a middle-ear infection, worsening the hearing problems. This common complication of colds is particularly prevalent in babies and toddlers. An estimated 5 in 6 children will get at least one ear infection by their third birthday, according to the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Compared with those of adults, children's Eustachian tubes are smaller and more horizontal, rather than set on a steep angle, making it more difficult for them to drain fluids out of the ear.

Middle-ear infections can temporarily decrease the perceived volume of sounds by up to 40 decibels, producing a similar sensation to wearing a pair of ear plugs, according to a 2022 review published in the journal Cureus. Recurring or untreated infections of the middle ear can eventually cause a perforation of the eardrum and, in the most severe cases, permanent hearing loss, the review notes.

But thankfully, the mild hearing loss that people experience during a cold usually goes away on its own once the illness resolves.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Anna Gora is a health writer at Live Science, having previously worked across Coach, Fit&Well, T3, TechRadar and Tom's Guide. She is a certified personal trainer, nutritionist and health coach with nearly 10 years of professional experience. Anna holds a Bachelor's degree in Nutrition from the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, a Master’s degree in Nutrition, Physical Activity & Public Health from the University of Bristol, as well as various health coaching certificates. She is passionate about empowering people to live a healthy lifestyle and promoting the benefits of a plant-based diet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus