80,000-year-old stones in Uzbekistan may be the world's oldest arrowheads — and they might have been made by Neanderthals

Small stone points discovered in Uzbekistan may be the earliest evidence of arrowhead technology.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Tiny stone artifacts discovered in Uzbekistan may be the oldest known arrowheads, a new study suggests.

It remains unclear whether these stone tools were created by modern humans, Neanderthals or some other group.

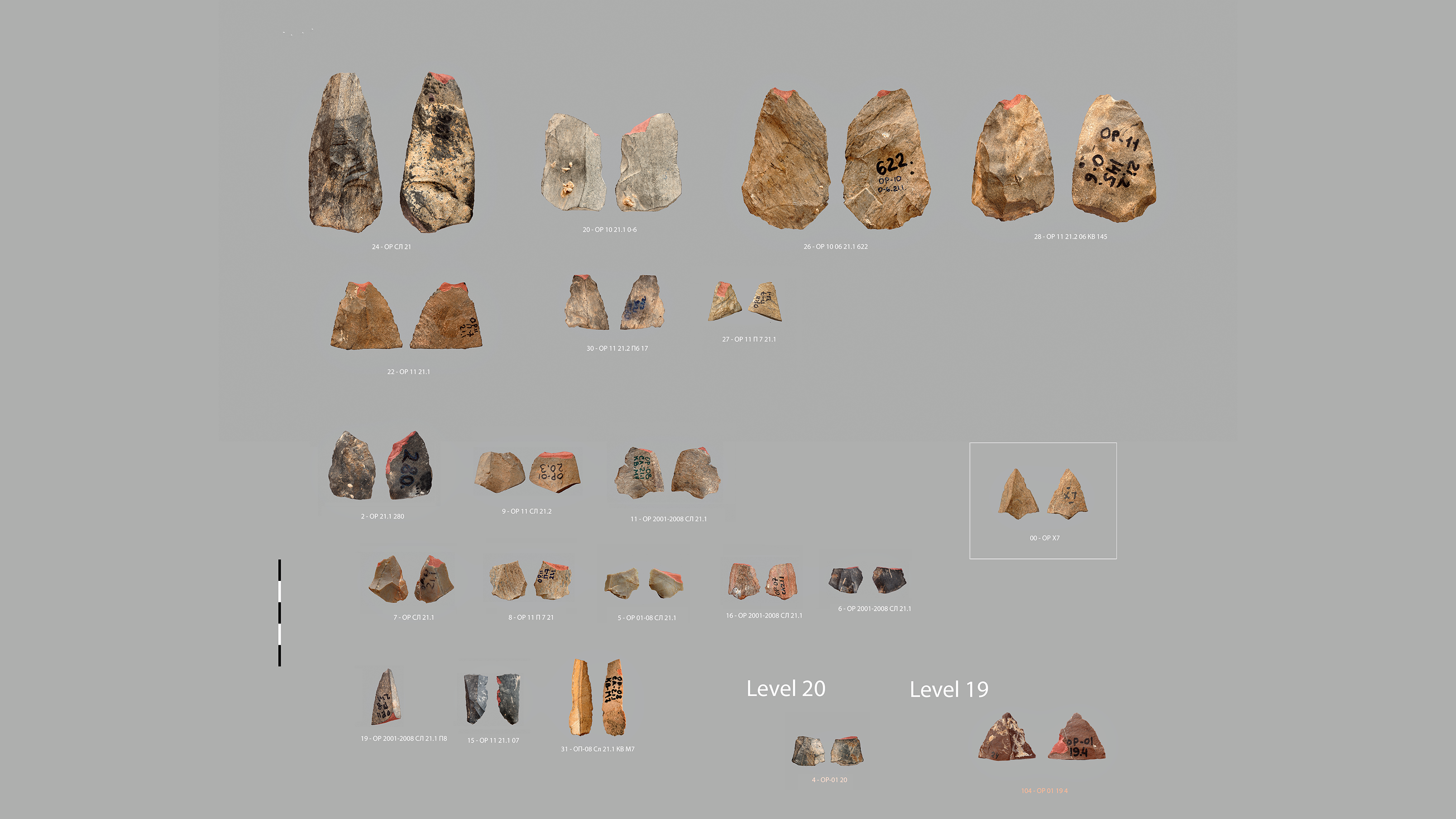

Archaeologists found the tools at the site of Obi-Rakhmat in northeastern Uzbekistan. Previous excavations uncovered a variety of stone tools at the site, such as thin and wide blades, and smaller "bladelets." But numerous small, triangular points — called "microliths" — were overlooked in prior work because they were broken.

Now, in a study published Aug. 11 in the journal PLOS One, the researchers argue that these "micropoints" are too narrow to have fit onto anything other than arrow-like shafts. The stones also display the kind of damage that would be expected from used arrowheads, study co-author Hugues Plisson, an associate scientist at the University of Bordeaux in France, told Live Science.

These micropoints, which are about 80,000 years old, may therefore be the oldest arrowheads in the world — around 6,000 years older than 74,000-year-old artifacts unearthed in Ethiopia, the researchers say.

The scientists expect their work to raise doubts.

"The bows themselves and the arrow shafts have not been preserved, so some skepticism from colleagues is expected," study co-author Andrey Krivoshapkin, director of the Siberian branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences' Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, these findings suggest "complicated early weapons and hunting technologies were more geographically widespread at an earlier date than previously supposed," Christian Tryon, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Connecticut who did not take part in this research, told Live Science. "As usual, we consistently underestimate the abilities of our ancestors."

It remains uncertain which group created the stone artifacts found at Obi-Rakhmat.

While excavating at the site in 2003, archaeologists discovered six teeth and 121 skull fragments from a child between 9 and 12 years old. Although the teeth resembled those of Neanderthals, the skull's features were more ambiguous, raising the question of whether the child was a member of our species, or possibly a hybrid between Homo sapiens and a Neanderthal or Denisovan.

Central Asia was Neanderthal territory when the oldest of these potential arrowheads were made in Obi-Rakhmat, Plisson said. However, there are no known Neanderthal arrowheads, the study noted. The researchers suggested the Obi-Rakhmat artifacts were most likely created by H. sapiens.

"The appearance of the Obi-Rakhmat population in Central Asia coincides with the presumed time of the dispersal of anatomically modern humans in Eurasia," Krivoshapkin said. The researchers told Live Science that these migrants might have originated from the Levant, the eastern Mediterranean region that today includes Israel, the Palestinian territories, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and some surrounding areas.

When modern humans arrived, the region that included Obi-Rakhmat may have already been inhabited by other groups, such as Neanderthals, the scientists contended, adding that the microlith technology could have helped them obtain food in their new environment.

"Our discovery helps us identify the subsistence characteristics that allowed the Obi-Rakhmat people to successfully compete with groups who had long since adapted to living in the landscapes we are studying," Krivoshapkin said.

The scientists are now attempting to discover when the people of Obi-Rakhmat first arrived in Central Asia. They hope to find archaeological and genetic links between them and groups in the Levant. They also plan to investigate other, potentially older archaeological sites in the region, which may reveal arrowheads even older than 80,000 years.

"These innovations could have appeared much earlier and persisted over a long period," Krivoshapkin said.

"It would be wonderful to find the sites where the hunting actually took place," Tryon said. "But these sites are difficult to find on the landscape."

Human evolution quiz: What do you know about Homo sapiens?

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus