72 million-year-old 'blue dragon' unearthed in Japan is unlike anything we've ever seen, experts say

The near-complete remains of a never-before-seen mosasaur that dominated the ancient Pacific Ocean have been unearthed in Japan. The great white shark-size creature is unlike any other aquatic animal, dead or alive.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists in Japan have unearthed the near-complete remains of an ancient, great white shark-size sea monster that likely terrorized the ancient oceans it used to inhabit. The prehistoric predator, which researchers have named "blue dragon," has an unusual body plan that sets it apart from its extinct relatives and is unlike any living creature.

The exceptional fossils, which are around 72 million years old, were discovered along the Aridagawa River in Wakayama Prefecture on Honshu island. They belong to a never-before-seen species of mosasaur — a group of air-breathing aquatic reptiles that were apex marine predators during the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago). The "astounding" remains are the most complete mosasaur fossils ever uncovered in Japan and the northwest Pacific, researchers wrote in a statement.

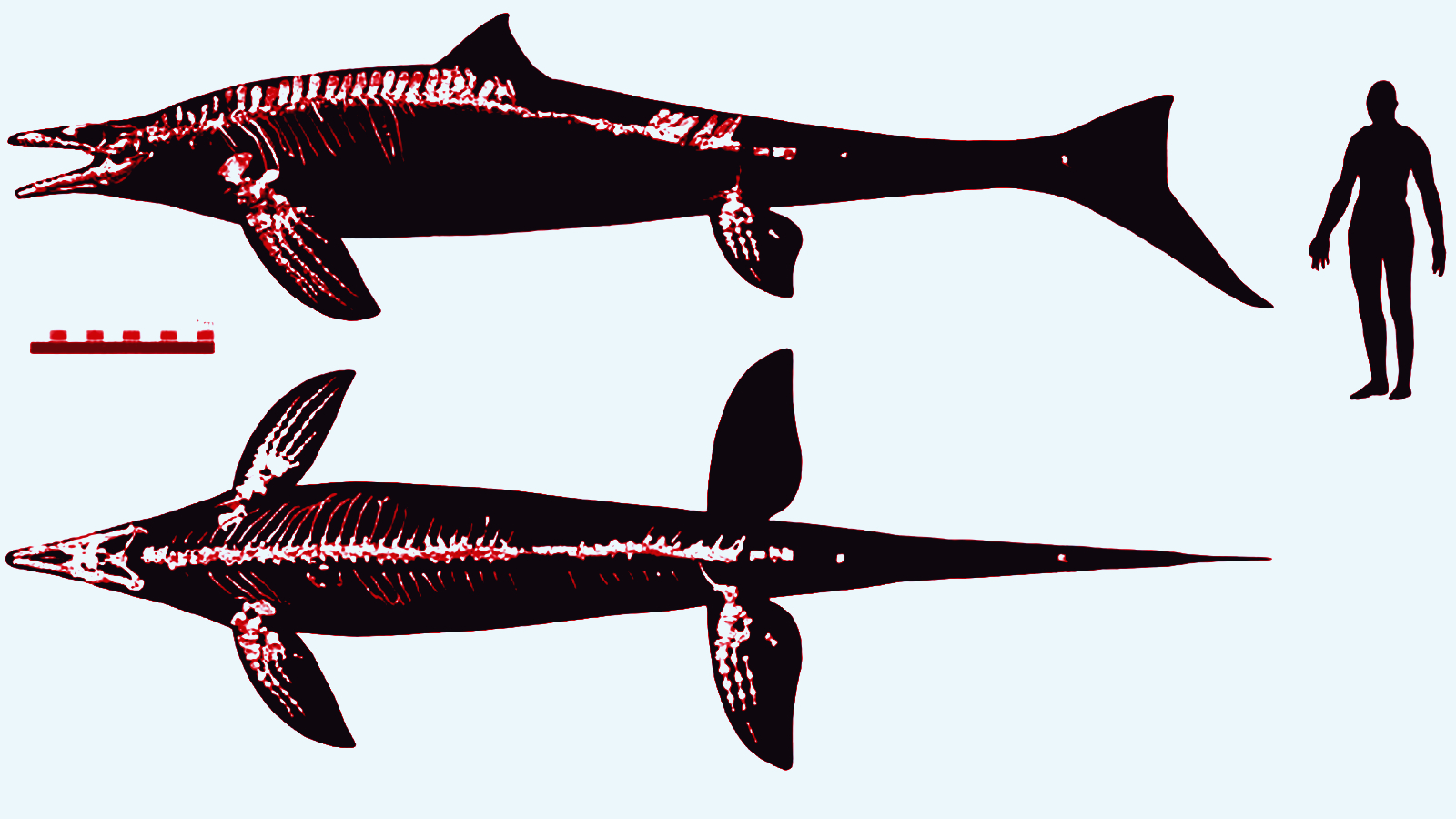

In a new study published Dec. 11 in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, researchers named the new mosasaur Megapterygius wakayamaensis. The new genus Megapterygius translates to "large-winged" after the creature's unusually large rear flippers, and the species name wakayamaensis recognizes the prefecture where it was found. The team nicknamed the creature the Wakayama Soryu — a soryu is a blue-colored aquatic dragon from Japanese mythology.

Mosasaurs share a similar body plan and there is very little variation among species. But M. wakayamaensis is something of an outlier, which has surprised scientists.

"I thought I knew them [mosasaurs] quite well by now," study lead author Takuya Konishi, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Cincinnati, said in the statement. But "immediately, [I knew] it was something I had never seen before."

Related: Oldest 'fish-lizard' fossils ever found suggest these sea monsters survived the 'Great Dying'

Like other mosasaurs, M. wakayamaensis had a dolphin-like torso with four paddle-like flippers, an alligator-shaped snout and a long tail. But it also had a dorsal fin like a shark or dolphin, which is not seen in any other mosasaur species.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, what confused researchers the most was the size of the new mosasaur's rear flippers, which were even longer than their front flippers. Not only is this a first among mosasaurs but it is also extremely uncommon among all living and extinct aquatic species.

Almost all swimming animals have their largest flippers toward the front of their bodies, which helps them steer through the water. Having larger flippers at the rear of the body would be like driving a car by steering the rear wheels instead of the front ones, which would make it much harder to turn quickly.

"We lack any modern analog that has this kind of body morphology — from fish to penguins to sea turtles," Konishi said. "None has four large flippers they use in conjunction with a tail fin."

The researchers suspect that instead of using the rear flippers to turn, M. wakayamaensis angled them upward or downward to quickly dive down or ascend through the water column, which may have helped make them adept hunters. The dorsal fin could have made it easier for the creature to turn, which may have counteracted the extra drag from the rear flippers, they added.

"It opens a whole can of worms that challenges our understanding of how mosasaurs swim," Konishi said.

M. wakayamaensis was about the same size as great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), which grow to around 16 feet (4.9 meters) long. But other species could grow up to 56 feet (17 m), which is longer than a school bus.

Mosasaurs emerged around 100 million years ago and died off around 66 million years ago along with the nonavian dinosaurs after a massive asteroid struck Earth. During the last 20 million years of their existence, the terrifying sea lizards were the aquatic equivalent of Tyrannosaurs rex and sat at the top of the food chain, thanks in part to the disappearance of other top marine predators such as ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs, the researchers wrote.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus