Oldest 'fish-lizard' fossils ever found suggest these sea monsters survived the 'Great Dying'

The fossilized remains of an ichthyosaur dating back to shortly after the Permian mass extinction suggest that the ancient sea monsters emerged before the catastrophic event.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ancient "fish-lizards" were swimming around in Earth's oceans 250 million years ago, long before scientists thought they first emerged, a new study finds.

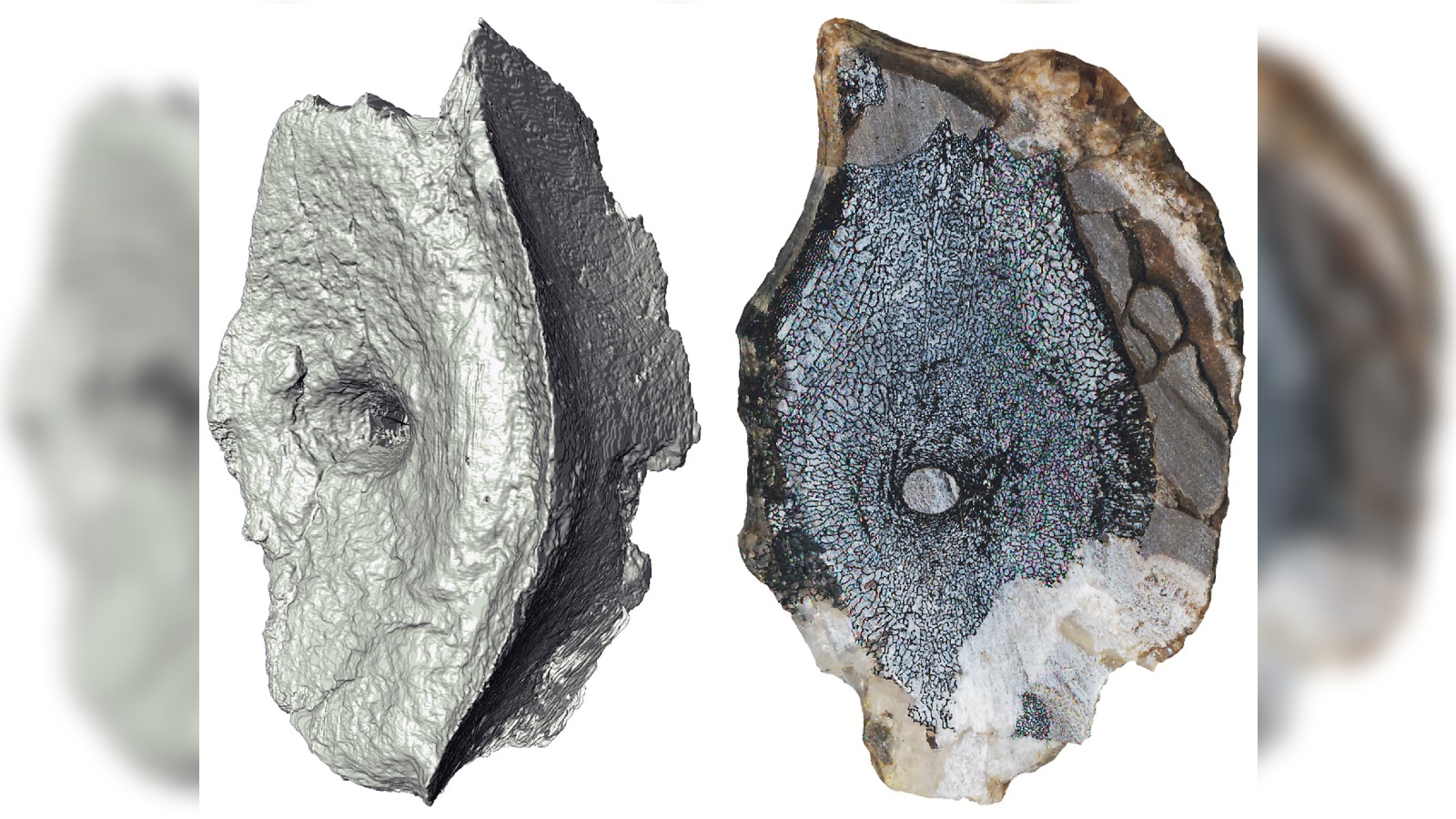

Researchers discovered the fossilized remains of an ichthyosaur on Spitsbergen, a remote Arctic island in the Svalbard archipelago in Norway in 2014. Ichthyosaurs are an extinct, fish-like lizard whose body shape resembled that of modern-day dolphins and toothed whales. The remains, which consist of 11 tail vertebrae, were trapped within a limestone boulder that dated to the early Triassic period, which makes the fossils the oldest ichthyosaur remains ever uncovered and the oldest evidence of marine reptiles.

Scientists previously assumed that ichthyosaurs had emerged along with all other marine reptiles after the Permian mass extinction event, also known as the "Great Dying," which occurred around 251.9 million years ago and wiped out around 90% percent of all life on Earth at the time. Until now, the oldest-known marine reptile fossils belonged to smaller and less aquatically advanced groups and dated to 249 million years ago, which suggested that marine reptiles had emerged shortly after the destructive event.

But in a new study, published March 13 in the journal Current Biology, researchers argue that the size and composition of the ichthyosaur bones are evidence that the gigantic ocean predators may have emerged before the Permian extinction took place.

Related: 55-foot-long Triassic sea monster discovered in Nevada

Icthyosaurs and other marine reptiles are believed to have descended from land-dwelling reptiles that slowly transitioned into the water to fill an ecological niche that had been left open after the disappearance of oceanic predators. As a result, the first marine reptile species were not perfectly suited to an aquatic lifestyle and likely had dense bones, less streamlined bodies and did not grow to large sizes.

In April 2022, researchers announced the discovery of a tooth from one of the largest ichthyosaurs to ever swim in Earth's oceans that was likely larger than the current record holder Shastasaurus sikanniensis, which measured 69 feet (21 meters) long.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The newly uncovered ichthyosaur's vertebrae are the same size as those found in later ichthyosaurs, which grew to around 9.8 feet (3 m) long. The bones also have a spongy structure that appears to be well adapted to aquatic life. The team therefore suspects that the ichthyosaur lineage likely emerged before the end-Permian mass extinction because they were unlikely to have evolved these advanced traits in the less than 2 million years after the catastrophic event occurred.

The results could force palaeontologists to reconsider what they thought they knew about the Permian mass extinction event.

"It now seems that at least some groups predated this landmark interval," the researchers wrote in a statement. Fossils from other ancient ichthyosaur ancestors and other dinosaur-era reptiles may also be waiting to be found elsewhere in the world, they added.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus